Mark Rappaport makes movies that look, sound and feel like nobody else’s movies. He is an original. He has discovered and recorded his own universe in the same sense that William Blake, Lewis Carroll, J. R. R. Tolkein or Charles Addams have. You enter it on his terms, because it’s his fantasy, but you get caught up in it immediately.

It’s a universe in which a handful of central characters adapt postures and attitudes towards each other in the midst of the broadest possible melodramatic structures. Their stories are bizarre or sad or overwhelmingly banal, but their visual universe is meticulously controlled: The art direction on a Rappaport film (by Lilly Kilvert this time) is as important as the script or direction.

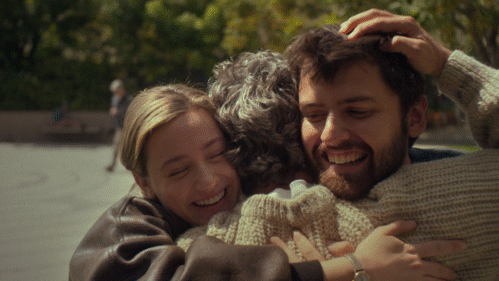

In his new “The Scenic Route” (which arrives at Chicago Filmmakers on Saturday straight from the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes), he gives us three primary characters: Two sisters, Estelle and Lena, and a young man named Paul who lives first with Estelle, then with Lena, and then with both. Lest this sound like a steamy scenario, I should point out that Rappaport’s characters rarely move very much, and tend to find themselves in formal tableaux

They do talk occasionally, but the main weight of the story is carried by voices on the sound track. Estelle begins the story by describing a 19th Century engraving on a wall: It shows a man behind bars looking down at the prone naked body of a woman whose bed is borne on the ocean. What does the picture mean? Nothing much… until Lena comes to visit and has a print of the same engraving… or when Estelle duplicates the scene in the engraving with Paul behind the bars. Images double back upon themselves, suggest hidden meanings, create a sinister undercurrent by refusing to “stand” for anything except the characters’ obsession with them.

Estelle has not been lucky in love. Early in the film, her former husband visits and attacks her. Paul double-crosses her with her sister. There is a perfect street scene in which the husband, Estelle and Paul meet, and the two men “size each other up like professional boxers,” Estelle says on the sound track, while she stands between them.

Meaning is carried by body language, by posture, by small shifts in expression in faces and eyes. Paul, for example, is almost totally silent and immobile socially. Estelle fantasizes about what he must be thinking. His silence is actually aggression, and perhaps the movie is finally about Estelle’s inability to find anybody to whom she can communicate except in the most simplistic terms.

The movie’s jammed with images, fantasies, symbols and stunning visuals (as when a visit to the country is presented by having the characters stand in front of the movie’s characteristic paneled wallpaper — and then having the “wall” slowly levitate to reveal the country behind them).

Yet despite this richness, the things the people actually manage to say to one another are usually barren and lifeless. (And yet, paradoxically, the movie is often very funny.)

“The Scenic Route” is Rappaport’s first feature in color (his “Local Color,” in black and white, naturally, played earlier this year at the Film Center). It’s a movie of great, grave, tightly controlled visual daring, and you have never seen anything like it before. It never reveals its mysteries… and I never wanted it to.