“The Proposition” plays like a Western moved from Colorado to Hell. The characters are familiar: The desperado brothers, the zealous lawman, his civilized wife, the corrupt mayor, the old coots, the resentful natives. But the setting is the Outback of Australia as I have never seen it before. These spaces don’t seem wide open because an oppressive sky glares down at the sullen earth; this world is sun-baked, hostile, unforgiving, and it breeds heartless men.

Have you read Blood Meridian, the novel by Cormac McCarthy? This movie comes close to realizing the vision of that dread and despairing story. The critic Harold Bloom believes no other living American novelist has written a book as strong and compares it with Faulkner and Melville, but confesses his first two attempts to read it failed, “because I flinched from the overwhelming carnage.”

That book features a character known as the Judge, a tall, bald, remorseless bounty hunter who essentially wants to kill anyone he can, until he dies. His dialogue is peculiar, the speech of an educated man. “The Proposition” has such a character in an outlaw named Arthur Burns, who is much given to poetic quotations. He is played by Danny Huston in a performance of remarkable focus and savagery.

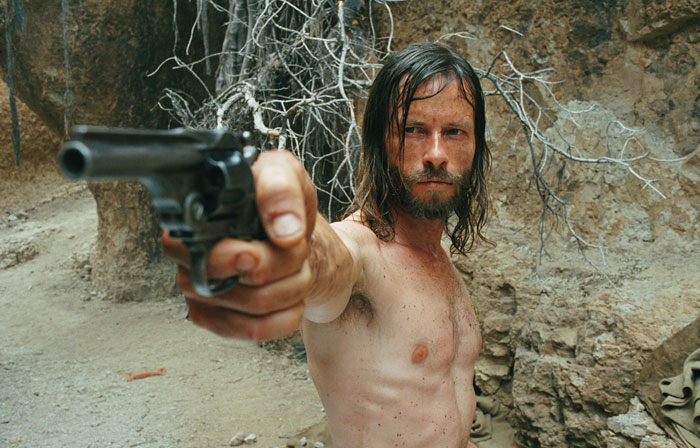

Against him is Captain Stanley (Ray Winstone), who is not precisely a sheriff since this land is not precisely a place where the law exists. He is more of an Ahab, obsessed with tracking down Arthur Burns and his brothers Charlie (Guy Pearce) and Mike (Richard Wilson). They are not merely outlaws, desperados, villains, but dedicated to evil for its own sake, and the film opens with a photograph labeled “Scene of the Hopkins Outrage.” The Burns boys murdered the Hopkins family, pregnant wife and all, perhaps more for entertainment than gain.

Ray Winstone, who often plays villains, is one of the best actors now at work in movies (see him in “Sexy Beast,” “Ripley's Game,” “Last Orders“). Here he plays a man who would be fearsome enough in an ordinary land, but pales before the malevolence of the Burns brothers. He lives with Martha (Emily Watson), his fragrant wife from England, who fences off a portion of wilderness, calls it their lawn, plants rose bushes there, serves him his breakfast egg and behaves, as colonial women did in Victorian times, as if still at “home.”

“I will civilize this land,” Captain Stanley says. In the 1880s, it is an achievement as likely as Ahab capturing the whale. He is able to capture Charlie and Mike Burns: Mike, a youth like the Kid in Blood Meridian, still half-formed but schooled only in desperation, and Charlie, an inward, brooding, damaged man whose feelings are as instinctive as a kicked dog. The Captain is not happy with his prisoners, because he lacks the real prize. He makes a proposition to Charlie. If Charlie tracks and kills his brother Arthur, the Captain will spare both Charlie and Mike.

Charlie sets off on this mission. He feels no particular filial love for Arthur; they are bonded mostly by mutual hatred of others. The Captain himself ventures out on the trail, finding such settlers as have chosen to live in exile and punishment. The most colorful — no, “colorful” is not a word for this movie — the most gnarled and cured by the sun is Jellon Lamb, played by John Hurt as if he is made of jerky.

Why do you want to see this movie? Perhaps you don’t. Perhaps, like Bloom, it will take you more than one try to face the carnage. But the director John Hillcoat, working from a screenplay by Nick Cave, has made a movie you cannot turn away from; it is so pitiless and uncompromising, so filled with pathos and disregarded innocence, that it is a record of those things we pray to be delivered from. The actors invest their characters with human details all the scarier because they scarcely seem human themselves. In what place within Arthur Burns does poetry reside? What does he feel as he quotes it? What does Martha, the Emily Watson character, really think as she uncrates a Christmas tree she has had shipped in from another lifetime? If Captain Stanley is as tender toward her as he seems, why has he brought her to live in these badlands?

What of the land itself? There is a sense of palpable fear of the Outback in many Australian films, from “Walkabout” to “Japanese Story,” not neglecting the tamer landscapes in “Picnic at Hanging Rock.” There is the sense that spaces there are too empty to admit human content. There are times in “The Proposition” when you think the characters might abandon their human concerns and simply flee from the land itself.

And what of the aborigines, who inhabit this landscape more or less invisibly, and have their own treaty with it? The Stanleys have a house servant named Two Bob, played by Tommy Lewis, who sizes up the situation and walks away one day, carefully removing his shoes, which remain in the garden.