Not long ago I saw the first of the great screen epics about Moses and his people, the 1923 silent version of Cecil B. de Mille’s “The Ten Commandments.” Everyone must be familiar with de Mille’s 1956 sound version, which plays regularly on television. Now here is “The Prince of Egypt,” an animated version based on the same legends. What it proves above all is that animation frees the imagination from the shackles of gravity and reality, and allows a story to soar as it will. If de Mille had seen this film, he would have gone back to the drawing board.

The story of Exodus has its parallels in many religions, always with the same result: God chooses one of his peoples over the others. We like these stories because in the one we subscribe to, we are the chosen people. I have always rather thought God could have spared man a lot of trouble by casting his net more widely, emphasizing universality rather than tribalism, but there you have it. Moses gives Rameses his chance (free our people and accept our God) and Rameses blows it, with dire results for the Egyptian side.

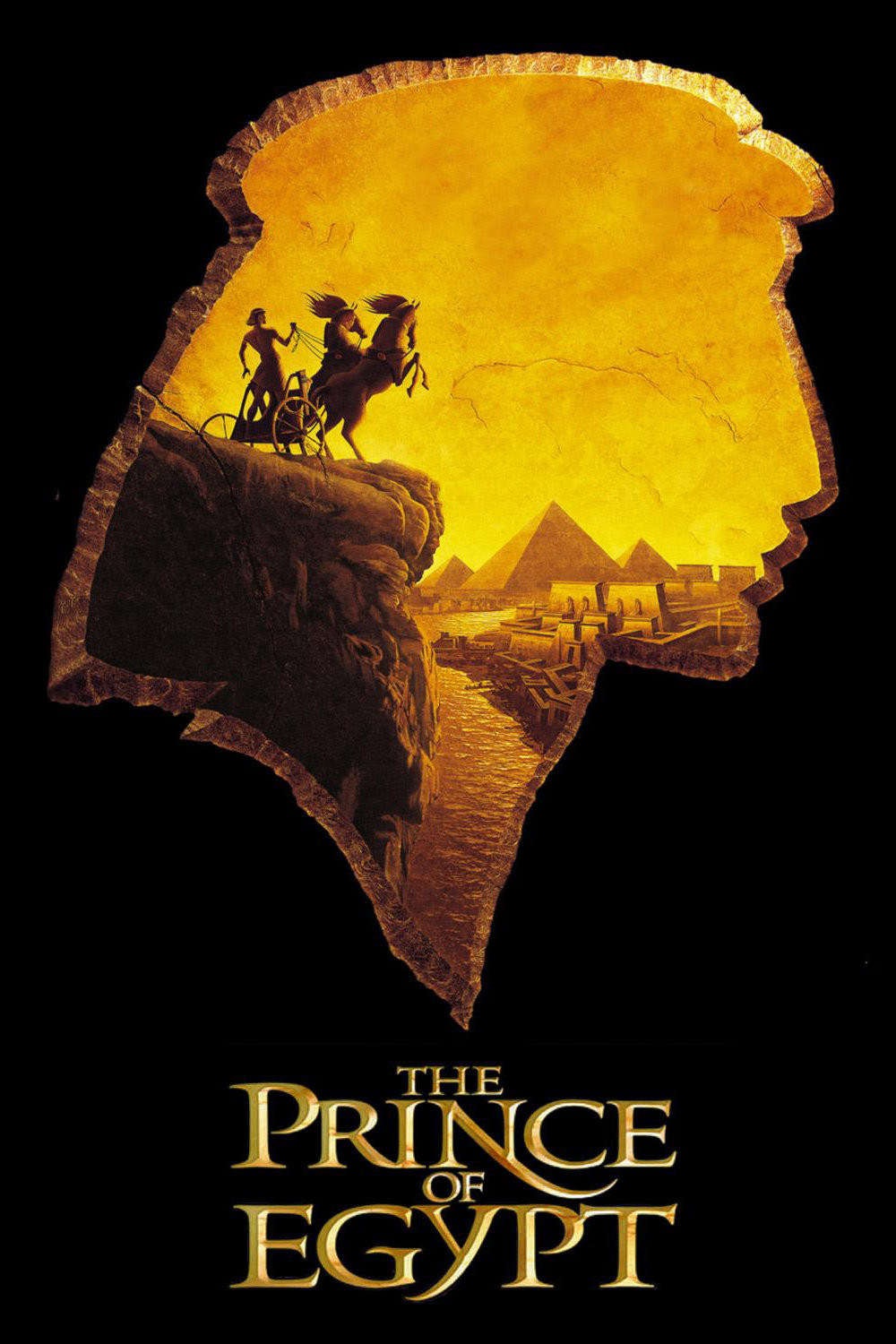

“The Prince of Egypt” is one of the best-looking animated films ever made. It employs computer-generated animation as an aid to traditional techniques, rather than as a substitute for them, and we sense the touch of human artists in the vision behind the Egyptian monuments, the lonely desert vistas, the thrill of the chariot race, the personalities of the characters. This is a film that shows animation growing up and embracing more complex themes, instead of chaining itself in the category of children’s entertainment.

That’s established dramatically in the wonderful prologue scenes, which show the kingdom and Hebrew slaves building pyramids under the whips of the Pharaoh’s taskmasters. The “sets” here are inspired by some of the great movie sets of the past, including those in de Mille’s original film and D.W. Griffith’s “Intolerance.” A vast Sphinx gazes out over the desert, and slaves bend to the weight of mighty blocks of stone. In crowd scenes, both here and when the Hebrews pass through the Red Sea, the movie uses new computer techniques to give the illusion that each of the countless tiny figures is moving separately; that makes the “extras” uncannily convincing.

The film follows Moses (voice of Val Kilmer) from the day when he is plucked from the Nile by the queen (Helen Mirren) to the day when he returns from the mountain with the Ten Commandments. What it emphasizes more than earlier versions is how completely the orphan child is taken into the family of the Pharaoh (Patrick Stewart); he is a well-loved adopted son who becomes the playmate and best friend of Rameses (Ralph Fiennes), the Pharaoh’s son. As boys, they get in trouble together (one drag race in chariots, which speed excitingly down collapsing scaffolds, results in the destruction of a temple). And when Rameses is named regent, his first act is to name Moses as royal chief architect.

But something within Moses knows that the Egyptians are not his people. After he happens to meet his real brother and sister, Aaron (Jeff Goldblum) and Miriam (Sandra Bullock), and learns the truth about his heritage, he runs away into the desert. At an oasis, Moses encounters a former slave girl, whom he had helped to escape from the Pharoah’s empire, and who is the daughter of the Hebrew high priest Jethro (Danny Glover). While staying with them, Moses hears the voice from the Burning Bush: “I am that I am, the God of your fathers.” For Moses, accepting this god means renouncing untold power and riches, and Rameses (now the Pharaoh) is first incredulous, then angered. “I am a Hebrew,” Moses sternly informs him, “and the God of the Hebrews came to me and commands that you let my people go.” When Rameses disagrees (and doubles the slaves’ workload), God unleashes a series of punishments. Fire rains from the sky, locusts descend in clouds, and all the first-born are killed. All leads up to the spectacular parting of the Red Sea, an event made for animation; unlike de Mille’s oddly unconvincing vertical walls of water, the parting here has an almost physical plausibility; we can see how the water parts and where it goes.

The movie is not shy about being entertaining, but it maintains a certain seriousness. In place of the usual twosomes and threesomes of little characters doing comic relief, we get two temple magicians (voices of Steve Martin and Martin Short), and a duet (“Playing With the Big Boys”). Moses turns his staff into a snake to impress Rameses, and magicians show how the trick has been done. It’s not that easy to explain the fire and the locusts.

The more movies I see, the more grateful I am for new films that go to the trouble of creating astonishing new images. One of the reasons I was so enthusiastic, earlier in 1998, about “Dark City,” “What Dreams May Come” and “Babe: Pig In The City” is that they showed me sights I had never imagined before, while most movies were showing me actors talking to one another. (Those who found “Dreams” cornball were correct, but they missed the point.) “The Prince of Egypt” is the same kind of film (as were, on quite a different scale, “A Bug's Life” and “Antz“). It addresses a different place in the moviegoer’s mind, one where vision, imagination and dream are just barely held in rein by the story. One imagines de Mille had a film like this in his mind, before he had to reduce it to reality.