Sometimes you have to wonder how certain movies get made. I have no special knowledge of the production of “The Legend of Tarzan.” But I have to imagine that the movie spent such a long time in the development process that no one involved found a moment to look outside the Hollywood bubble and surmise that maybe right now in America isn’t the most opportune time to reboot a pop culture myth involving a quasi-superhero white guy who has dominion over the animals and certain peoples of Africa.

The upper-case “r” in a circle that appears below the name “Tarzan” in the opening credits of this new movie, directed by “Harry Potter” stalwart David Yates from a script by Craig Brewer (of “Hustle and Flow” and “Black Snake Moan” renown, and no, I’m not kidding) and Adam Cozad (no idea), may have something to do with the movie’s raison d’etre—when one has a trademark, one must exploit it. But the wisdom of propagating any kind of white savior narrative during the charged era of Black Lives Matter surely must have seemed dubious, no?

Actually, yes, because throughout its brisk hour-and-forty-five minute running time, “The Legend of Tarzan” does things to reassure those viewers that care that the movie is indeed aware of its “problematics.” The movie begins with some texts evoking the colonization of what was in the late 19th century called the Belgian Congo, and of a nefarious scheme involving mercenaries, slave labor, and pilfered diamonds, all engineered by an envoy named Leon Rom. This fellow is played by Christoph Waltz and he carries with him a rosary that sometimes doubles as a short-distance noose, which isn’t a heavy-handed piece of symbolism at all, no way. Anyway, he’s the bad guy, and he’s first seen entering the deepest, foggiest, most spear-ridden caverns of the African jungle to bargain with fierce chief Mbonga (Djimon Hounsou), who will give Rom all the diamonds he needs to finance his army … on delivery of his most hated enemy: Tarzan.

The movie finds Tarzan up in England, all civilized and respectable and Lord Greystoke-like, residing in his manor with wife Jane, something of a London celebrity and man of influence. The ruse of an invitation to check out Belgian’s “progress” in the Congo is proffered to Tarzan—this is part of Rom’s trap—and Tarzan, I mean Lord Greystoke, I mean John Clayton, is disinclined to accept. He’s moved, though, by the entreaties of an African-American diplomat/investigative agent, George Washington Williams (Samuel L. Jackson), who wants to tag along with, um, Tarzan, and get solid evidence of illegal slave trading. That’s travel companion one. Once the Big T gets back to the manor, we discover that he and Jane have a pretty 21st-century type relationship. She, played by Margot Robbie, insists that she’s coming along too. He protests “The last thing you need is more stress”—I told you about that 21st century biz—but she’s not having it. The gang of three hits the sea, and once on the Continent makes a meaningful detour to visit the tribe that Jane knew when her parents were missionaries. And there is much singing and celebration in a manner not unlike that scene in “Hatari!” where they make Elsa Martinelli the elephant queen or whatever she was. Almost sixty years and ain’t a damn thing changed in Hollywood.

Is that entirely true? As the presence of Jackson here somewhat attests, “The Legend of Tarzan” does make some attempts to address contemporary racial sensibilities/sensitivities. Almost every time something potentially dicey rears its head in the narrative, the movie practically pauses to excuse itself and say, “I know what you’re thinking, but it isn’t what you think, just wait,” and then, what do you know, Jackson’s character will chime in with an ironic apercu to remind everyone that we’re all friends here, and it’s the guy with the German accent and the rosary who’s the real problem.

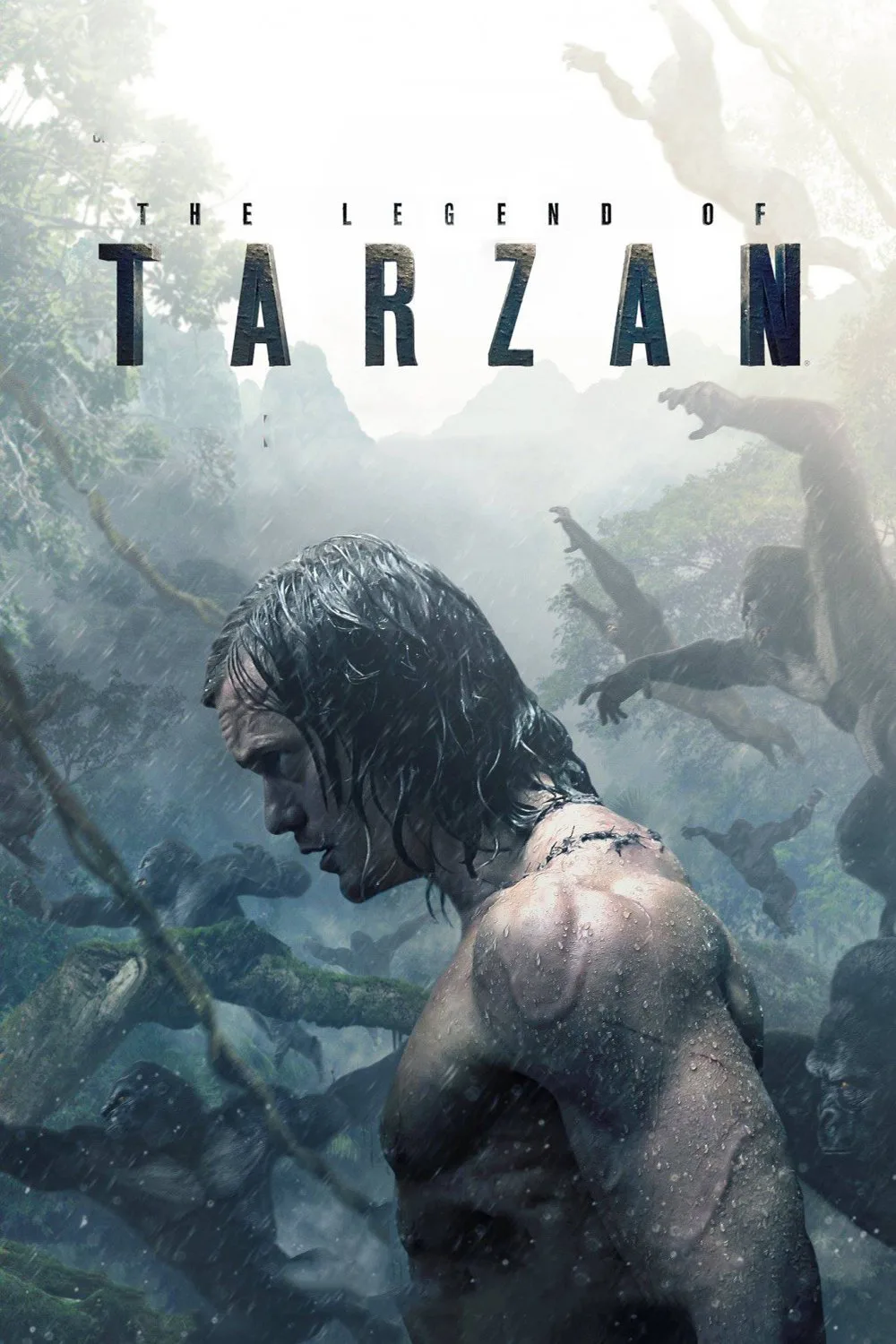

Still, once Hans Landa, I mean Leon Rom, does show up to spoil the happy homecoming of Tarzan and Jane, laying ruin to the tribal village and kidnapping Jane, the movie does provide an object lesson on what is and is not, apparently, acceptable in the violent-entertainment scheme of things. A peaceful, noble African tribal leader can take a bullet to the chest, but once she’s been abducted, Jane can only have the threat of rape dangled in front of her and the audience. (Waltz’s performance as the villain is terribly familiar, but it’s kind of funny that he’s kitted out as if he wants the title role in a remake of “Fitzcarraldo.”) The way the semiotics play out should be somewhat queasy-making even if you aren’t paying close attention. Even after the movie establishes that Tarzan is a uniter, not a divider, the compromise he strikes with his most fearsome African nemesis is only accomplished after we’re treated to the spectacle of ultra-buff Alexander Skarsgård putting the hurt on about a dozen men of color. (And if you’re asking right about now why I have to bring politics, racial or otherwise, into it, one answer I have is that the movie did it first, by deigning to create a revisionist history of the Belgian Congo.)

Strangely enough, though, if you can put these considerations aside—or, I suppose, if you never cared about such considerations in the first place—“The Legend of Tarzan” is a pretty good action-adventure movie. Its narrative is refreshingly free of bloat, folding the Tarzan origin story into a series of relatively pain-free flashbacks that actually dovetail credibly into its contemporary scenario. The lead players, with the exception of the too-familiar Waltz, give appealing performances, and the action scenes are pretty tight. I am amused that somebody took the “Blazing Saddles” joke about stampeding cattle through the Vatican as a sort of inspiration for a climactic set piece, but I also have to admit the conceit works. For what it’s worth, “The Legend of Tarzan” is several unpretentious cuts above the pompous, leaden “Greystoke” of over thirty years ago. (I’m ignoring the 1998 “Tarzan and the Lost City” because nobody even saw it, let alone talked about it.)