A lot of movies begin with poetic quotations, but “The Hurt Locker” opens with a statement presented as fact: “War is a drug.” Not for everyone, of course. Most combat troops want to get it over with and go home. But the hero of this film, Staff Sgt. William James, who has a terrifyingly dangerous job, addresses it like a daily pleasure. Under enemy fire in Iraq, he defuses bombs.

He isn’t an action hero, he’s a specialist, like a surgeon who focuses on one part of the body over and over, day after day, until he could continue if the lights went out. James is a man who understands bombs inside out and has an almost psychic understanding of the minds of the bombers. This is all the more remarkable because in certain scenes, it seems fairly certain that the bomb maker is standing in full view — on a balcony or in a window overlooking the street, say, and is as curious about his bomb as James is. Two professionals, working against each other.

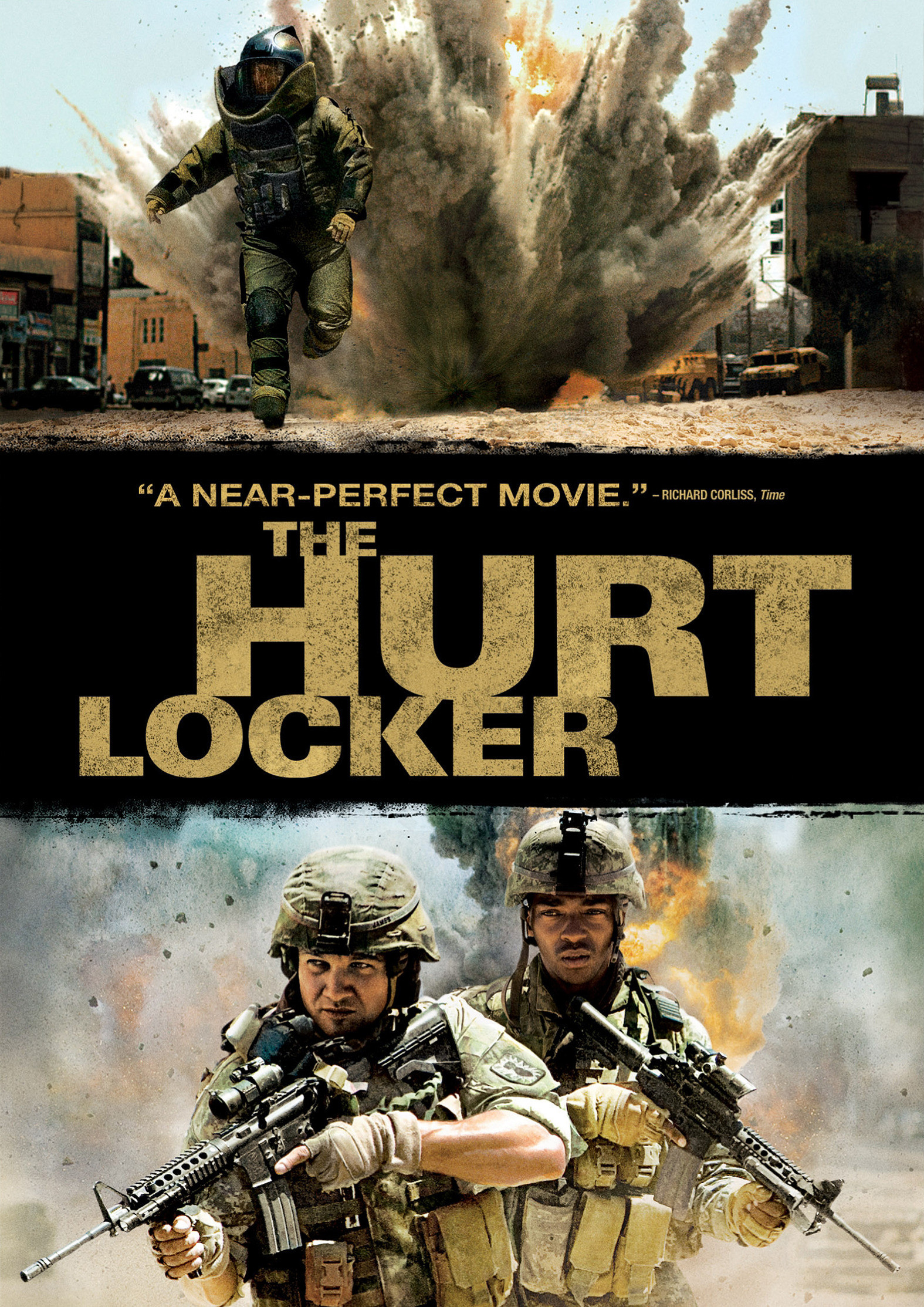

Staff Sgt. James is played by Jeremy Renner, who immediately goes on the short list for an Oscar nomination. His performance is not built on complex speeches but on a visceral projection of who this man is and what he feels. He is not a hero in a conventional sense. He cares not for medals. He could no doubt recite patriotic reasons for his service, but does that explain why he compulsively, sometimes recklessly, puts himself in harm’s way? The man before him in this job got himself killed. James seems even cockier.

“The Hurt Locker” is a spellbinding war film by Kathryn Bigelow, a master of stories about men and women who choose to be in physical danger. She cares first about the people, then about the danger. She doesn’t leave a lot of room for much else. The man who wrote “war is a drug” was Chris Hedges, a war correspondent for the New York Times. Mark Boal, who wrote this screenplay, was embedded with a bomb squad in Baghdad. He also wrote the superb “In the Valley of Elah” (2007), with Tommy Lee Jones as a professional Army man trying to solve the murder of his son who had just returned from Iraq. Also based on fact.

Bigelow and Boal know what they’re doing. This movie embeds itself in a man’s mind. When it’s over, nothing has been said in so many words, but we have a pretty clear idea of why James needs to defuse bombs. I’m going to risk putting it this way: (1) bombs need to be defused; (2) nobody does it better than James; (3) he knows exactly how good he is, and (4) when he’s at work, an intensity of focus and exhilaration consumes him, and he’s in that heedless zone when an artist loses track of self and time.

The most important man in his life is Sgt. J.T. Sanborn (Anthony Mackie), head of the support team that accompanies James. Sanborn and his men provide cover fire, scan rooftops and hiding places that might conceal snipers, and assist James into and out of his heavy protective clothing. Sanborn gives him constant audio feedback that James hears inside his helmet. It is Sanborn who has his eye on everything, who is nominally in charge, and not the tunnel-visioned James.

Sanborn is a skilled, responsible professional. He works by the book. He follows protocol. James drives him nuts. Sometimes James seems to almost deliberately invite trouble, and Sanborn believes that by following the procedure, they’ll all have a better chance of going home. He isn’t a shirker and he doesn’t have weak nerves. He’s a realist and thinks James is reckless.

Certainly James behaves recklessly at times, even in his use of protective clothing. He takes risks boldly. But in the actual task of defusing a bomb, he is as careful as if he were operating on his own heart. Bigelow uses no phony suspense-generating mechanisms in this film. No false alarms. No gung ho. It is about personalities in terrible danger. The suspense is real, and it is earned. Hitchcock said when there’s a bomb under a table, and it explodes, that’s action. When we know the bomb is there, and the people at the table play cards, and it doesn’t explode, that’s suspense.

“The Hurt Locker” is a great film, an intelligent film, a film shot clearly so that we know exactly who everybody is and where they are and what they’re doing and why. The camera work is at the service of the story. Bigelow knows that you can’t build suspense with shots lasting one or two seconds. And you can’t tell a story that way, either — not one that deals with the mystery of why a man like James seems to depend on risking his life. A leading contender for Academy Awards.

Revised 7/ 11/09