The key moment in “The Hurricane,” which tells the story of a boxer framed for murder, takes place not in a prison cell but at a used-book sale in Toronto. A 15-year-old boy named Lesra spends 25 cents to buy his first book, the autobiography of the boxer Rubin “Hurricane” Carter. As he reads it, he becomes determined to meet the boxer and support his fight for freedom, and that decision leads to redemption.

The case and cause of Hurricane Carter are well known; Bob Dylan wrote a song named “Hurricane,” and I remember Nelson Algren’s house sale when the Chicago novelist moved to New Jersey to write a book about Carter. Movie stars and political candidates made the pilgrimage to Carter’s prison, but his appeals were rejected and finally his case seemed hopeless.

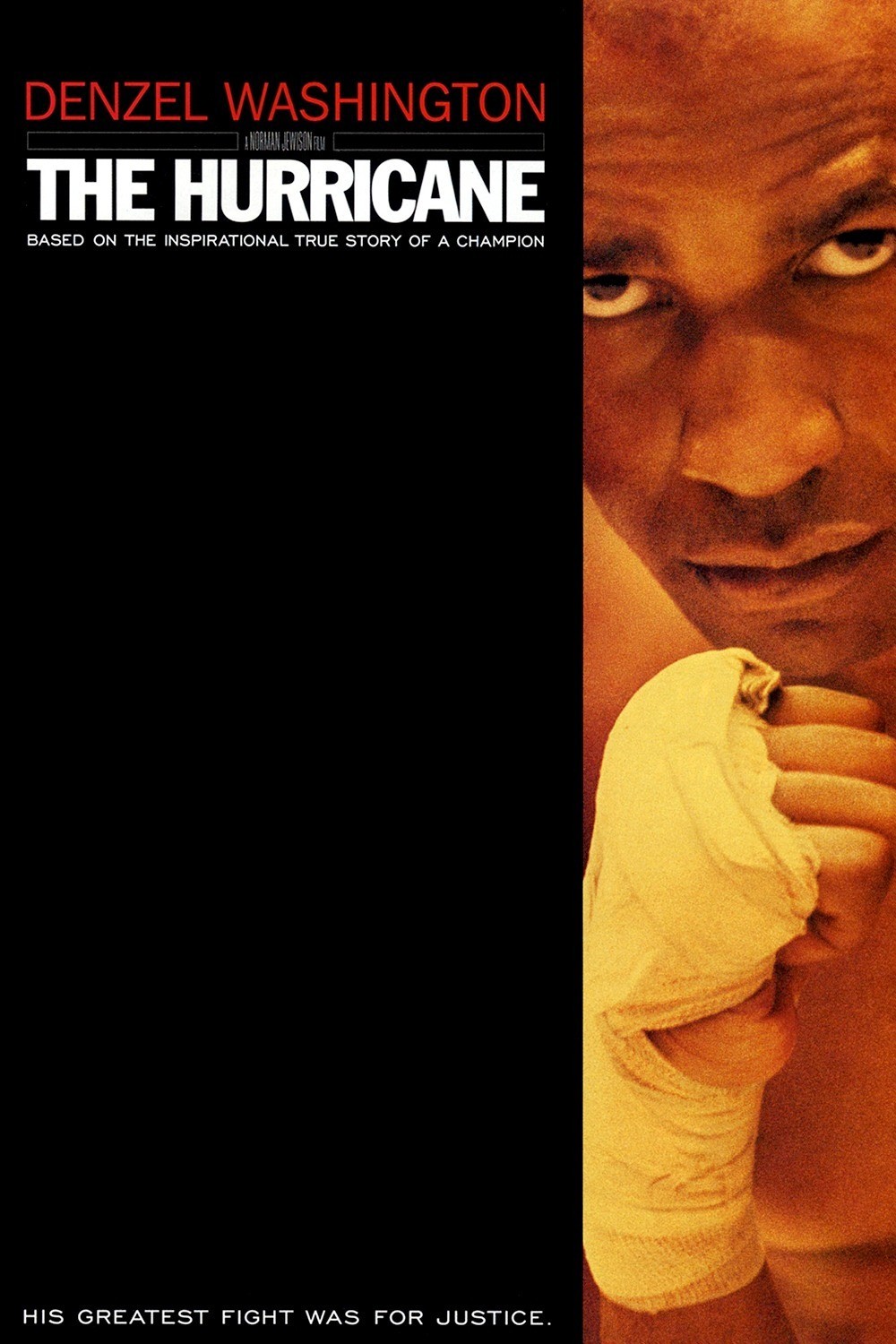

This film tells his story–the story of a gifted boxer (Denzel Washington) who was framed for three murders in Patterson, N.J., and lost 19 years of his life because of racism, corruption and–perhaps most wounding–indifference. In the film, the teenage boy (Vicellous Reon Shannon), who is from New Jersey, enlists his Canadian foster family to help Carter, and they find new evidence for his defense attorneys that eventually leads to his release. The villain is a cop named Vincent Della Pesca (Dan Hedaya), who essentially makes it his lifelong business to harm Carter.

Norman Jewison’s film starts slowly, with Carter’s early years and his run-ins with Della Pesca. In my notes I wrote: “If this is going to be the story of a persecuting cop, we need to know him as more than simply the instrument of evil”–as a human being rather than a plot convenience. We never do. Della Pesca from beginning to end is there simply to cause trouble for Carter. Fortunately, “The Hurricane” gathers force in scenes where Carter refuses to wear prison clothing and learns to separate himself mentally from his condition. Then young Lesra enters the picture, and two people who might seem to be without hope find it from each other.

This is one of Denzel Washington’s great performances, on a par with his work in “Malcolm X.” I wonder if “The Hurricane” is not Jewison’s indirect response to an earlier controversy. Jewison was preparing “Malcolm X” with Washington when Spike Lee argued that a white man should not direct that film. Jewison stepped aside, Lee made a powerful film with Washington–and now Jewison has made another. Washington as Hurricane Carter is spare, focused, filled with anger and pride. There is enormous force when he tells his teenage visitor and his friends, “Do not write me. Do not visit me. Find it in your hearts to not weaken me with your love.” But the Canadians don’t obey. They move near to Trenton State Prison, they meet with his lead defense attorneys (David Paymer and Harris Yulin), they become amateur sleuths who help take the case to the New Jersey Supreme Court in a do-or-die strategy. It always remains a little unclear, however, just exactly who the Canadians are, or what their relationship is. They’re played by Deborah Kara Unger, Liev Schreiber and John Hannah, they share a household, they provide a home for Lesra, a poor African-American kid from a troubled background, and we wonder: Are they a political group? An unconventional sexual arrangement? I learn from an article by Selwyn Raab, who covered the case for the New York Times, that they were in fact a commune. Raab’s article, which appeared the day before the film’s New York opening, finds many faults with the facts in “The Hurricane.” He says Carter’s defense attorneys deserve much more credit than the Canadians. That Carter was not framed by one cop with a vendetta, but victimized by the entire system. That Carter’s co-defendant John Artis (Garland Whitt) was a more considerable person than he seems in the film. That events involving the crime and the evidence have been fictionalized in the film. That Carter later married the Unger character, then divorced her. That Lesra broke with the commune when it tried for too much control of his life.

News travels fast. Several people have told me dubiously that they heard the movie was “fictionalized.” Well, of course it was. Those who seek the truth about a man from the film of his life might as well seek it from his loving grandmother. Most biopics, like most grandmothers, see the good in a man and demonize his enemies. They pass silently over his imprudent romances. In dramatizing his victories, they simplify them. And they provide the best roles to the most interesting characters. If they didn’t, we wouldn’t pay to see them.

“The Hurricane” is not a documentary but a parable, in which two lives are saved by the power of the written word. We see Carter’s concern early in the film that the manuscript of his book may be taken from his cell (it is protected by one of several guards who develops respect for him). We see how his own reading strengthens him; his inspirations include Malcolm X. And we see how his book, which he hoped would win his freedom, does so–not because of its initial sales, readers and reviews, but because one kid with a quarter is attracted to Hurricane’s photo on the cover. And then the book wins Lesra’s freedom, too.

This is strong stuff, and I was amazed, after feeling some impatience in the earlier reaches of the film, to find myself so deeply absorbed in its second and third acts, until at the end I was blinking at tears. What affects me emotionally at the movies is never sadness, but goodness. I am not a weeper and have really lost it only at one film (“Do the Right Thing“), but when I get a knot in my throat it is not because Hurricane Carter is framed, or loses two decades in prison, but that he continues to hope, and that his suffering is the cause for Lesra’s redemption.

That is the parable Jewison has told, aiming for it with a sure storyteller’s art and instinct. The experts will always tell you how a movie got its facts wrong (Walter Cronkite is no doubt correct that Oliver Stone’s “JFK” is a fable). But can they tell you how they would have made the movie better? Would “The Hurricane” have been stronger as the story of two selfless lawyers doing pro bono work for years? And a complex network of legal injustice? And a freed prisoner and a kid disillusioned with a commune? Maybe. Probably not.