For a movie about a larger-than-life personality who shook up the world with his brazenness—and since has had to seek political asylum because of it—”The Fifth Estate” feels unfortunately small and safe.

Director Bill Condon tells the story of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange in a way that seems insular and familiar. It is a tried-and-true tale of rise and fall—of a self-made political and cultural phenomenon whose ambitions are tidily explained away through pop psychology.

The man who has dared to post millions of classified documents online—ones which could potentially compromise both national security and individuals’ well-being—certainly must be more than a self-aggrandizing troublemaker. (Although the 42-year-old Australian does continue to issue insistent missives from the Ecuadorian embassy in London, which has protected him for over a year now.)

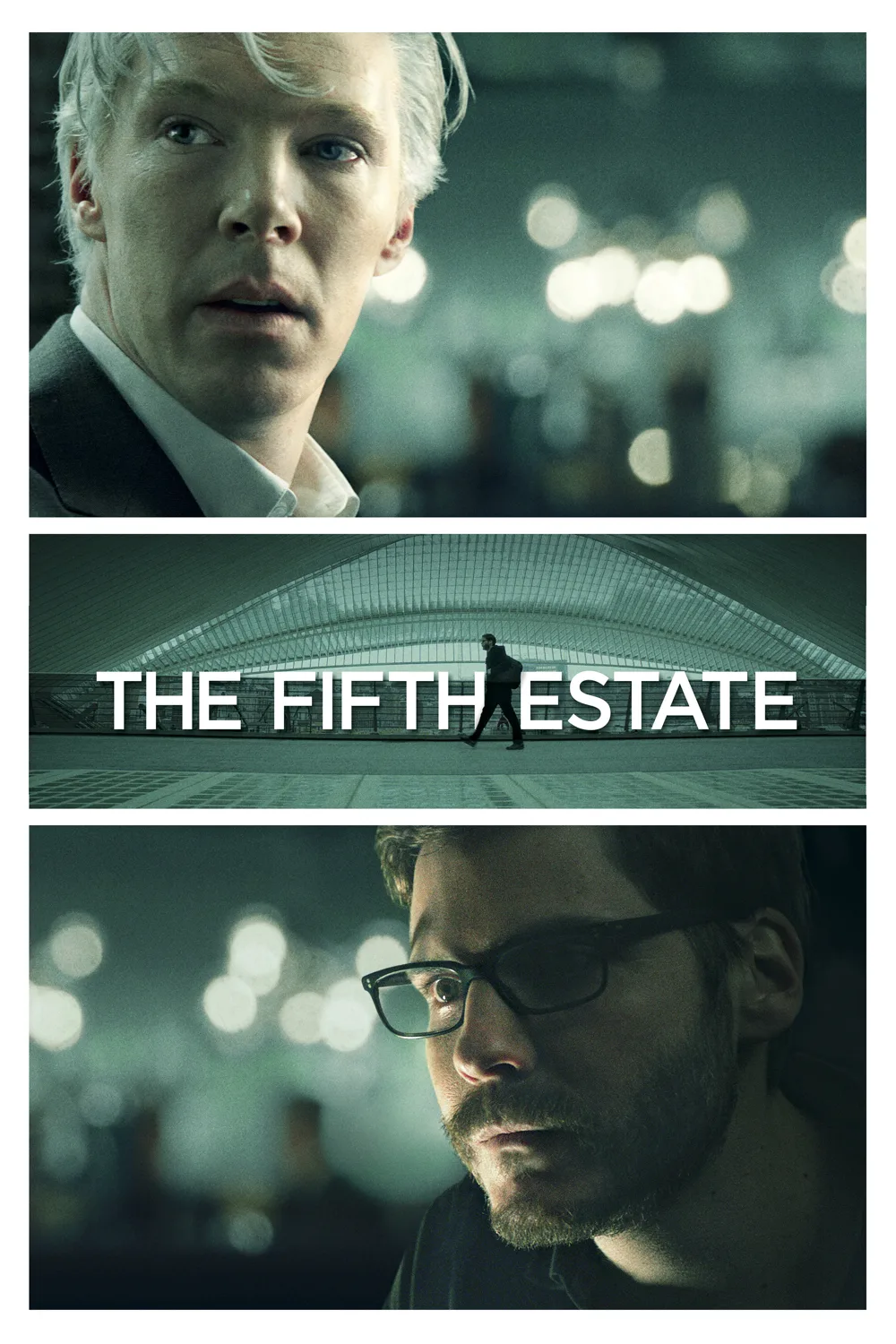

In the hands of a supremely creepy Benedict Cumberbatch, it’s easy to imagine how this persuasive, commanding force has mystified the world at large and entranced a few key followers in particular. He’s off-putting yet beguiling, odd but elegant. He constantly spouts the need for transparency but lies to everyone around him. But despite Cumberbatch’s formidable presence, Assange remains elusive, a white-haired ghost—more of an idea than a fully fleshed-out and complicated man.

Maybe that’s the point of Josh Singer’s script, based on a couple of books: “Inside WikiLeaks: My Time With Julian Assange at the World’s Most Dangerous Website” by Daniel Domscheit-Berg and “WikiLeaks: Inside Julian Assange’s War on Secrecy” by David Leigh and Luke Harding. But it does make it hard to get a grasp on him as a viewer, which is problematic given that he’s the engine that drives the film’s action.

About that action: Sitting at a laptop typing away furiously isn’t the most inherently cinematic pursuit. (Trust me, I’m doing it right now, you wouldn’t want to see it.) David Fincher solved that puzzle in “The Social Network” by creating a vivid, thrilling sense of place and through Aaron Sorkin’s sharp, lively dialogue. Condon has found clever, emotionally honest avenues into real-life figures in his previous films “Gods and Monsters” and “Kinsey” and shown a flair for the theatrical with “Dreamgirls” and the two-part “Twilight” finale; here, he tries to dramatize his characters’ interior lives through a motif that’s overly simplistic and rather gimmicky.

He envisions a giant office filled with multiple desks where multiple Assanges hammer away, exposing the truth. (Assange repeatedly informs skeptics and fans alike that WikiLeaks “has thousands of volunteers,” when actually it’s just him and his hardworking second-in-command, Berg, played by Daniel Brühl.) This sprawling room also serves as the imaginary location of the submission platform, where whistle-blowers could offer up secrets while maintaining anonymity through a complex encryption system. When it all begins to fall apart and the pressure becomes too much, “The Fifth Estate” depicts Berg smashing all that imaginary office furniture in a way that looks like a tantrum and comes off as more of a laughable moment than a startling one.

Condon is also too reliant on montages to cram in a ton of information while simultaneously providing a sense of movement as Assange and Berg hop from one major European city to the next collecting secret information. To the tune of Carter Burwell’s thumping techno score to go with the frequently sleek architecture, this technique often makes “The Fifth Estate” feel like a glossy travelogue: Look, they’re in Brussels! Now they’re in Stockholm! Ooh, Reykjavik looks pretty!

The film begins in October 2010—which seems like a lifetime ago in the Internet age—with The New York Times, The Guardian and Der Spiegel simultaneously publishing WikiLeaks’ Iraq War Logs: 400,000 classified U.S. military documents about the war in Iraq. Editors in all three cities anguish over pressing the button and blasting the story to the world. The moment also provides a flashback to when the German technology expert Berg first met Assange in 2007, quickly fell under his spell and became the fledgling website’s first volunteer. Berg is intended as our everyman conduit but compared to the shiny Assange, he’s rather dull; Brühl registers far more effectively as the precise and demanding racecar driver Niki Lauda in Ron Howard’s “Rush.”

From there, “The Fifth Estate” follows Assange’s rise to celebrity as WikiLeaks reveals more and more secret and damning information. But aside from a few scenes involving Stanley Tucci, Laura Linney and Anthony Mackie as U.S. government officials wringing their hands and shuffling papers—truly, these supporting roles are a huge waste of three great actors—we don’t get much of a sense of the global repercussions of the documents’ disclosure. A subplot involving a threat to a longtime asset of Linney’s character in Libya (Alexander Siddig, also underused) feels underexplored; it’s a blip, when in truth his situation is emblematic of the huge moral quandary that arises repeatedly when WikiLeaks chooses to expose every classified word.

“The Fifth Estate” seems more interested in contributing to a cult of personality, rather than cultivating a serious debate.