Shadowy figures circle a glass-walled house. They find an unlocked door and enter; once inside, they head straight for the bedroom. Sleigh Bells’ “Crown on the Ground” — scrunched guitar and speaker-wrecking drums — kicks in. The figures’ faces are now visible; they’re high school kids — several girls and a boy. They open the door of the bedroom closet and start grabbing necklaces, shoes and purses.

This is the first scene of “The Bling Ring,” Sofia Coppola’s unvarnished and occasionally problematic account of a string of burglaries committed by LA teenagers in 2008 and 2009. The opening credits identify “The Bling Ring” as “based on actual events,” instead of using the more common phrase “based on a true story”; this might seem like a minor distinction, but it’s an important one, because “story” implies a certain structure and viewpoint. Coppola’s approach to the subject is largely impartial; depending on the viewer, this can seem refreshing or off-putting.

Katie Chang and Israel Broussard star as the Ring’s leaders, Rachel Lee and Frank Prugo, here renamed Rebecca Ahn and Marc Hall. Rebecca and Marc meet at an alternative high school in Calabasas, and soon become close friends. Thrill-seeking petty thefts lead to burglaries and joyrides. At first they steal from neighbors and acquaintances, but soon begin to target celebrities, including Orlando Bloom, Lindsay Lohan, Rachel Bilson and Paris Hilton, whose house they are able to burglarize repeatedly without being noticed. Scouring gossip blogs for information, they wait until their targets are out of town to strike.

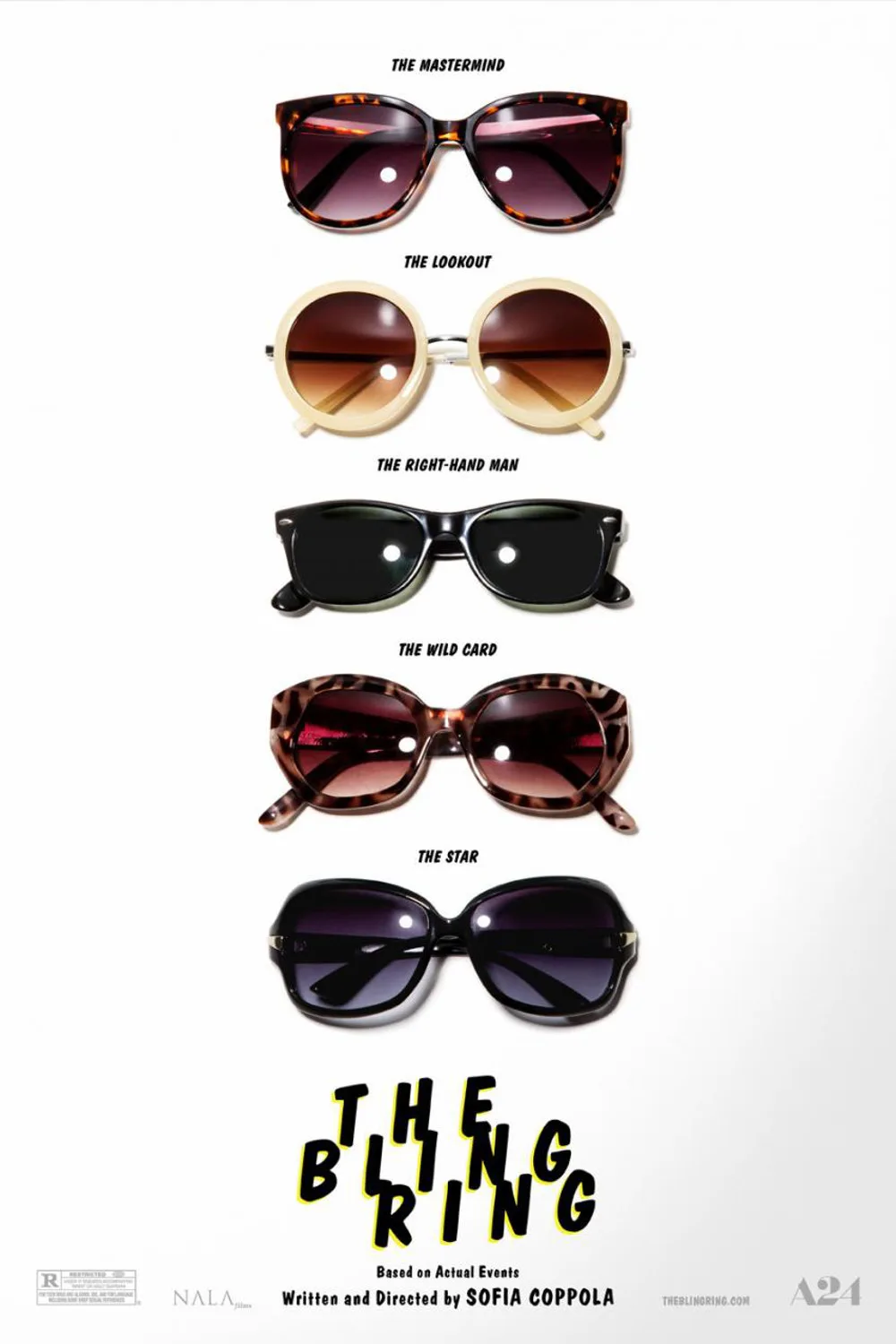

Rebecca and Marc’s “gang” quickly expands to include Chloe (Claire Julien), Sam (Taissa Farmiga), and Nicki (Emma Watson), a stand-in for the group’s most notorious member, Alexis Neiers. Chang, Broussard, Julien, and Farmiga all deliver uniformly strong, naturalistic performances; Watson, however, is “The Bling Ring”‘s premier scene-stealer. She plays Nicki as a sort of social mutant, the product of vapid New Age parenting irradiated with near-lethal doses of tabloid culture — less a personality than a collection of wants in search of immediate gratification.

The movie’s structure is programmatic; the gang party, then rob, then party, then rob, over and over. There’s not much in the way of narrative progression; like Coppola’s under-appreciated “Somewhere” (2010), “The Bling Ring” is more interested in describing a state of being — the mild numbness which comes with living at a safe distance from anything resembling hardship. The Bling Ring steal several million dollars in jewelry and clothes, most of which they keep for themselves; not content with being merely wealthy, they desire the lives of the super-rich. Regardless of how much money and comfort you have, there’s always someone to envy.

“The Bling Ring” represents the final work of Harris Savides, arguably the greatest American cinematographer of the past 15 years. (Savides died of brain cancer while the film was in post-production; “The Bling Ring” is dedicated to him.) Working in long, pliable takes, Savides and co-cinematographer Christopher Blauvelt are key in establishing the movie’s impartial tone; the scene where Rebecca and Marc rob reality TV star Audrina Patridge’s house — presented as a single wide shot with a glacial zoom — is emblematic of the movie’s detached, observational worldview.

However, a few things complicate Coppola’s approach. For one, there’s her disruptive use of stills and videos of celebrities; it’s meant to imitate the characters’ viewpoints — constantly looking at pictures in magazines and on websites — but instead breaks the visual rhythm established by Savides and Blauvelt. The implication is that these robberies are just an extension of the characters’ image-consumption — that these possessions are first and foremost cool pictures — but it’s conveyed in a way that’s so heavy-handed that it becomes a distraction.

For another, there’s the involvement of actual celebrities in a movie that’s overtly about celebrity-envy. Paris Hilton and Kirsten Dunst have non-speaking cameos as themselves; more importantly, Hilton’s real house is used throughout the film. The characters gawk at Hilton’s real possessions and rifle through her real closets.

This points to the movie’s most serious problem: the “impartial” viewpoint. Is “The Bling Ring” a movie about characters ogling at celebrities, or is it an excuse for the audience to ogle along with them? While Coppola’s attitude toward the Bling Ring isn’t entirely sympathetic, it isn’t overtly critical either; in fact, it often comes off as blasé.

All of Coppola’s films have focused on characters that are isolated from the world — movie stars (“Lost in Translation“, “Somewhere”), royalty (‘Marie Antoinette”), a strict family (“The Virgin Suicides”). Because the protagonists of most of these films are wealthy — after all, isolation is a luxury — and because Coppola has never shown much interest in depicting the world that these protagonists have separated themselves from, her work has often been accused of cultural myopia (Coppola, after all, was born into a family that’s the closest Hollywood has to a titled aristocracy). While that criticism isn’t entirely unearned (“Lost in Translation”, for one, is marred by ugly ethnic stereotyping), it overlooks the sensitivity that she brings to the material.

That sensitivity is largely absent in “The Bling Ring”; in its place is a void. Coppola neither makes a case for her characters nor places them inside of some kind of moral or critical framework; they simply pass through the frame, listing off name brands and staring at their phones. About an hour into the film, one starts to get the nagging feeling that Coppola’s “neutrality” is a dodge; she avoids moral commitment, thereby creating a movie ambiguous enough to be interpreted in several ways, but too vague to have much meaning in any interpretation.