You don’t need to squint very hard to see the satirical elements that might have elevated blood-soaked horror flick “The Belko Experiment” to greatness. The premise—a group of employees are forced to kill each other at the whims of an anonymous employer—is promising. But the script, penned by James Gunn (“Guardians of the Galaxy,” “Slither”), is undercooked, its violence foregrounded to the point of distraction. Many people will either love or hate this film based on how gory and aggressively cynical it is. But realistically, Gunn’s biggest conceptual failure is that his scenario is thoughtlessly cruel. The characters could have embodied traits of typical office drones and managers, turning the film into a savage black comedy. But those elements aren’t developed beyond a point, making the movie’s only selling point its excessive gore and violence.

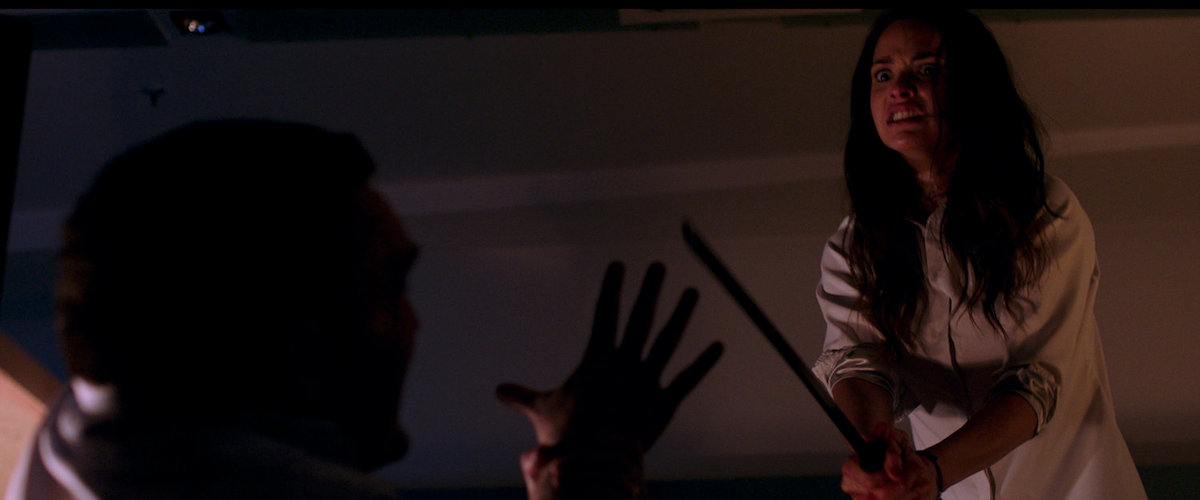

You’ll notice, from the start, how easy it is to either identify with or dismiss characters in “The Belko Experiment” based on how they respond to the stress of being told to kill their fellow employees. Never mind that stress makes people do crazy things: we’re supposed to sympathize with by-the-book employee Mike (John Gallagher Jr.) because he’s a moderate voice of reason compared to self-appointed megalomaniac Barry (Tony Goldwyn). Mike is the kind of guy who encourages his fellow employees to take the stairs, not the elevators while Barry is the kind of guy who says that the group should “consider our options” and think about cooperating with the mysterious uber-boss who’s compelling them to kill each other. Both characters clash sooner rather than later because each employee has a GPS micro-chip implanted in their heads—they are working in Bogota, where kidnappings are supposedly not uncommon—which is ultimately used as an explosive to pick off disobedient employees.

Secondary characters either voice their disapproval or support of Barry and Mike’s respective positions: Mike insists that nobody has “the right to choose who lives and who dies” while Barry suggests that they have no choice. You may, at some point, wonder if Barry has a point. But that moment will pass when you see the other guys he’s allied himself with, people like jittery, trigger-happy Lonny (David Dastmalchian) and sexual-harassment-happy Wendell (John C. McGinley). There’s no way to take the utilitarian position in this film because these guys are defined exclusively by personality-revealing bad behavior.

Conversely, there’s no way to relate to Mike because he’s such a generic goody-goody. What kind of guy warns people to take the stairs and not the elevators during such an emergency? That’s a half-serious question: I do not know anything about Mike beyond the fact that he handles stress well, talks other employees down from stress, and is a rational thinker given how much of the film’s early expository speculation comes from him (he’s a bit chatty at the start, but necessarily so since he’s essentially the lone voice of reason). There’s no way to tell what he was like before the Belko bosses starting killing their employees off, nor any way to know why we should sympathize with the character beyond the fact that he’s part of the solution and not the problem.

Then again, the lack of motivation could have also been a source of great comedy. Belko could be an office like any other: a place where bosses and fellow employees act kind and genial one minute but have the potential to transform into domineering thugs as soon as they fear they’re going to be thrown under the bus. That’s who Lonny, the most sympathetic of Gunn’s baddies, seems to be. But he’s annoyingly knock-kneed, and ineffectual, making him instantly unlikable. McGinley’s character is defined by his insincere toothy grin, and proud tendency of showing off his muscles, making his narcissism all too apparent. And Barry just wants to stay in control, as he shows when he undermines nice guy security guard Evan (James Earl) by breaking into the company’s weapons cache(!).

This makes a bloody, unpleasant series of murders the only reason to see “The Belko Experiment.” Director Greg McLean (“Wolf Creek,” “Rogue”) fails to distinguish himself during medium close-up shots of heads exploding and torsos flailing. But McLean’s contributions to “The Belko Experiment” aren’t what makes the film so disappointing. Gunn’s unimaginative conception of a “Battle Royale” meets “Office Space” style horror film—I just bet that that was the elevator pitch—holds a decent cast back from dying meaningful deaths. Even the most diehard gorehounds and Gunn supporters should give this stinker a pass.