“Shallow Grave” is a movie that might have warmed the heart of George Orwell, who in his famous essay “The Decline of the English Murder” complained that too many modern murders were simply unmotivated acts of squalid violence. “Let me try to define,” he wrote, “what it is that the readers of the Sunday papers mean when they fretfully say, `you never seem to get a good murder nowadays.’ ” In the golden age of murder, which he places between 1850 and 1925, “good murders” had several distinguishing characteristics. To begin with, the murderers were generally “little men of the professional class” – doctors, lawyers, the chairman of the local Conservatives. They lived in intense respectability in semidetached houses, so that strange noises could be heard by the neighbors. They killed not out of passion, but for convenience – to cover up an adultery or a theft, say. Their motive was often financial gain.

Their method was usually poison.

The great preoccupation in the golden age of murder was, of course, disposal of the body. The classic cases feature bathtubs full of acid, bones buried in the backyard, corpses bricked up in the wall or fed to the dogs. (The disappearance of Helen Vorhees Brach took on a special interest because of speculations along these lines.) Much of the enjoyment, for newspaper readers, came from the notion of respectable professional people desperately hauling bodies about by moonlight.

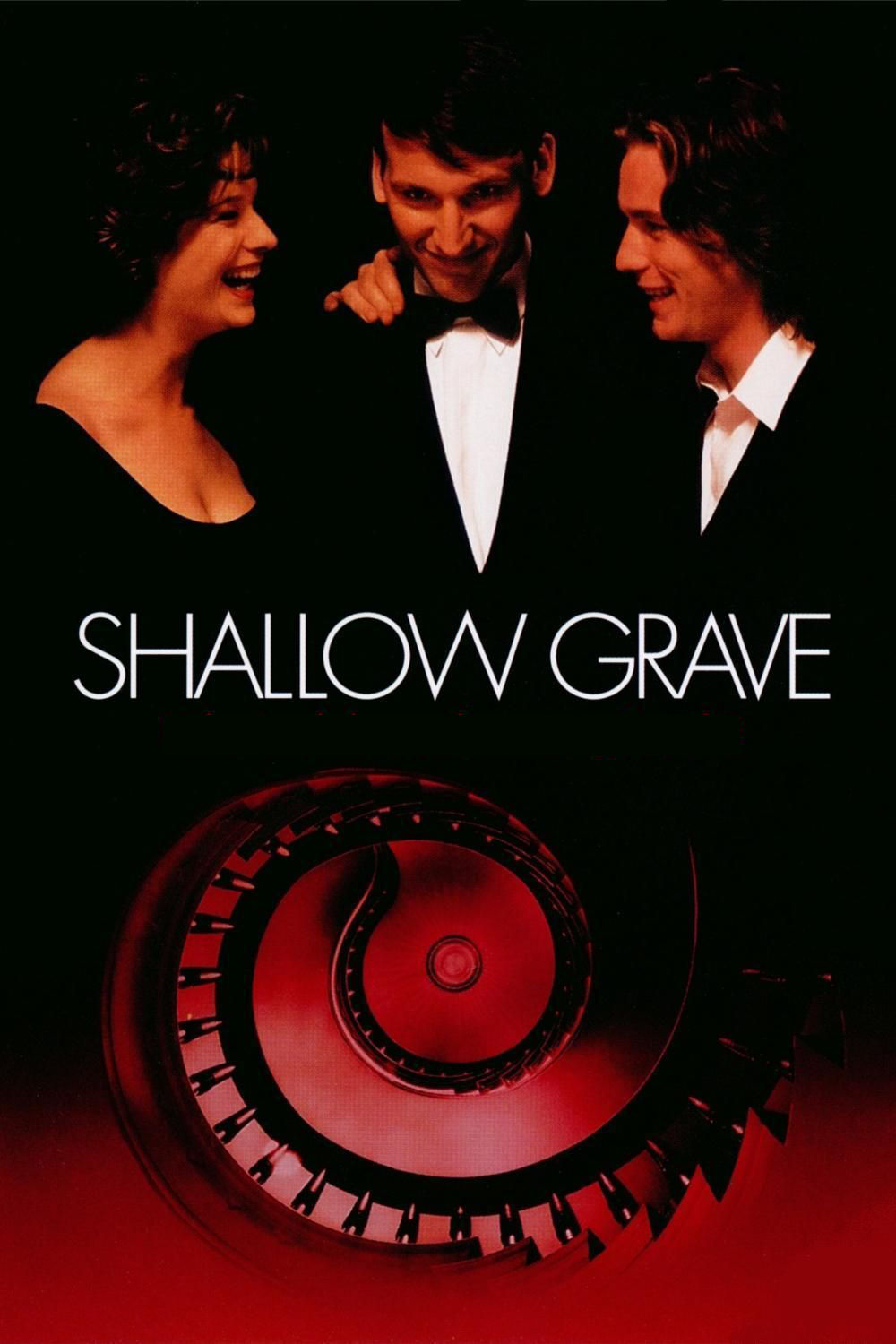

“Shallow Grave” does not supply a perfect murder by Orwell’s standards – the first victim kills himself with drugs before his nasty new roommates can form any designs on him. But it qualifies in many other ways. The movie takes place in Glasgow, Scotland, where three roommates are interviewing for a fourth. They are particularly repulsive types of supercilious yuppie twits: a doctor, an accountant and a journalist. They delight in humiliating and mocking applicants, until finally they find a customer tough enough to impress them: Hugo (Keith Allen), a cool wise guy. “He’s . . . interesting,” says Juliet (Kerry Fox), the doctor.

Hugo moves in and is found dead of an overdose the next morning, sprawled on his red bedspread (in a shot inspired by the famous painting “The Death of Chatterton”). This quite annoys his new roommates, until they discover that his suitcase is filled with cash.

Then they decide that since no one knows he has come to live with them, they should dispose of the body and keep the cash.

This involves doing unsavory and unthinkable things that are completely outside their experience: cutting off the corpse’s head, hands and feet to prevent identification. Burying the remains.

Incinerating the severed parts in the hospital where Juliet works.

Alex (Ewan McGregor) and David (Christopher Eccleston) certainly don’t want to perform the dismemberment. They think Juliet should.

(“But Juliet – you’re a doctor! You kill people every day!”) The director, Danny Boyle, wants the disposal scenes to be funny, as he backlights his fastidious characters desperately sawing away at the bones of the dead. There is a touch here of the Coen brothers’ “Blood Simple,” but if you want to see how a great director gets laughs with the con trast between gruesome deeds and the desire to avoid dry-cleaning bills, look at Martin Scorsese’s “Goodfellas.” Back at the flat, the desperate situation becomes more unmanageable. The three grow paranoid, and David, the meek accountant, moves into the attic with the cash, drilling holes in the ceiling so he can spy on the activities below. A series of visitors arrive at the flat and discover it is unwise to go up into the attic.

The body count mounts.

All of the materials are in place for a film that might have pleased Orwell. But somehow they never come together. One of the problems, I think, is that all three conspirators are so unpleasant.

Not evil – that would be fine, in material like this – but simply obnoxious in a boring way. To some degree we need to identify with their fear of discovery, and we do not: The only likable character is the police inspector (Ken Stott), who asks insinuating questions and then exchanges significant looks with his assistant.

The bottom line in any great murder case, I believe, is the sneaky suspicion that there, but for the grace of God, go we – either as victim or, in our nightmares, murderer. Since no reasonable person can remotely hope to identity with Juliet, David or Alex, the whole case drops through.