“He didn’t really pay attention to anything else—or anybody else. Marcel Proust explained that very well. He said that if you are a genius you are busy with yourself—and it is true. Voilà.”—Pierre Berge, Yves Saint Laurent’s partner both in business and, sometimes, in life, from a 2012 interview after he was asked whether the French fashion icon was always creating.

It wasn’t easy being Saint Laurent. But, often enough, it could be tres amusant. That is, if a wallow in Fellini-esque excess that involves bottomless glasses of pricey champagne, bins full of sedatives and hallucinogens, louche high-society types, easy pre-AIDS sex of every stripe, pulsing electronica music and gorgeous vapid people lounging about are your thing. Basically, the Rive Gauche version of Studio 54.

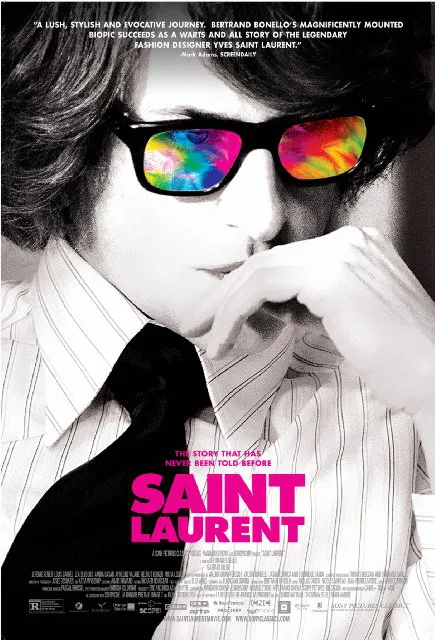

That seems to be the theme of “Saint Laurent,” an epic-length biopic (not to be confused with last year’s “Yves Saint Laurent,” a briefer and less juicy authorized account) about the enigmatic master of haute-couture fabulousness who died from a brain tumor in 2008 at age 71. Ultimately hollow as director Bertrand Bonello keeps his subject somewhat emotionally at bay, the movie is also at times quite addictive—much like Opium, the controversial name of Saint Laurent’s famous scent. As a diversion, it isn’t exactly good for you but it does provide entertainment.

The effect is something like those ennui-inducing Andy Warhol-sanctioned films (“Heat,” “Trash” and “Flesh”) crossed with one of Visconti’s grandiose period pieces such as “The Damned” and “Death in Venice,” all from the era that is the film’s focus. That Warhol crops up in a vocal cameo reading from a fan letter he wrote to the designer and Helmut Berger, a Visconti regular and also one of his lovers, plays the reclusive elder Saint Laurent from 1989 on, just emphasizes these intriguing connections.

But while “All About Yves” could have been a fitting title given the regular fits of narcissistic acting out that is indulged onscreen, the emphasis on the religious aspect of his name is also appropriate. This style innovator who gave the world the trapeze dress and tuxedos for women had more than a bit of a martyr complex—having to top yourself repeatedly is a special type of hell—and sought out some semblance of spirituality to ease his pain, as evidenced by the giant gold Buddha that was the centerpiece of his home décor.

Sprawling if scintillatingly shot, this is yet another portrait of a tortured male genius who suffered for his art while making the world a more beautiful place for the rest of us. That notion is re-enforced by the opening scene set in 1974, in which a barely cogent and exhausted Saint Laurent mysteriously checks himself into a fancy Paris hotel under the name of “Mr. Swann,” an apt reference to Proust’s famous character.

Why is he booking a room? “To sleep,” he says. Yet, instead of catching up on shuteye, the Algerian-born trend setter engages in his own remembrance of things past while conducting a clandestine telephone interview. He speaks of traumas suffered during his short stint in the French Army during the Algerian War and his subsequent treatment for mental problems, including pills and electroshock therapy—both of which likely contributed to lingering psychological issues and ongoing struggles with drug addiction.

However, there are very few other references to Saint Laurent’s beginnings. Often stunning in its baroque visuals though somewhat enervating in its free-flowing structure, this luxurious plunge into his peak period of creativity from 1967 to 1976 is less a straight-forward chronicle than an impressionistic depiction of its subject’s split personality: a slavish perfectionist pushed to his limits and a dedicated denizen of Parisian night life and all its hedonistic pleasures.

Bonello treats Saint Laurent like a vampire, holed up during the day in his sterile white work quarters as he churns out sketch after sketch of fresh designs as if possessed, his drawing hand flicking with the speed and grace of a hummingbird’s wings. After dark, Saint Laurent stalks young men lurking on the street in between clubbing sprees to satisfy his physical urges. But he also is drawn to fashion-forward women who provide him with muse-like inspiration and support.

As played by Gaspard Ulliel—all signature owlish glasses, floppy gold corona of curls, boyish grins and jutting cheekbones—Saint Laurent is nothing if not a contradiction. Early on, when he is working on his 1967 collection, he eyes a simple linen shift and decides to transform it into a more youthful ensemble by ripping off its sleeves. He steps back, admires the effect and finds it to be “as short, neat and precise as a gesture.”

The irony is that “Saint Laurent” the movie will have none of that as it messily shuffles the usual rise-and-fall trajectory of those who have a love-hate relationship with fame and a taste for deranged self-destructive behavior. It’s clear that once Saint Laurent erotically connects with model Jacques de Bascher (memorably embodied by actor Louis Garrel as if he were a member of the glam-rock duo Sparks on steroids), whose effete mustache and beckoning bedroom eyes promise nothing but trouble, rock bottom is not too far away.

Meanwhile, Jeremie Renier as Berge—who handled the ever-expanding corporate side of the YSL label and probably was the most important component to its success outside of Saint Laurent’s own talent—gets short shrift save for one semi-kinky bedroom assignation and a boardroom meeting.

If you come away remembering anything from this 150-minute movie as it overstays its welcome, it will be individual scenes rather than the overall effect, for that is where Bonello shines. One sequence involves a rich client trying on a beautiful yet stark jacket and matching skirt with a black blouse in a showroom. Somehow, it doesn’t make her feel special. Saint Laurent and a stylist quickly sprint into action, adding on a gold chain necklace and belt, opening up the shirt and having her loosen her hair. Suddenly, she is instantly transformed into a sexy, alluring creature. Would that the rest of “Saint Laurent” was as magical.