Ray Charles became blind at age 9, two years after witnessing the drowning death of his little brother. In a memory that haunted his life, he stood nailed to the spot while the little boy drowned absurdly in a bath basin. Why didn’t Ray act to save him? For the same reason all 7-year-olds do dumb and strange things: Because they are newly in possession of the skills of life and can be paralyzed by emotional overload. No one seeing the scene in “Ray,” Taylor Hackford‘s considerable new musical biography, would think to blame the boy, but he never forgives himself.

If he had already been blind, he could not have blamed himself for the death and would not have carried the lifelong guilt that, the movie argues, contributed to his eventual drug addiction. Would he also then have not been driven to become the consummate artist that he was? Who can say? For that matter, what role did blindness play in his genius? Did it make him so alive to sound that he became a better musician? Certainly he was so attuned to the world around him that he never used a cane or a dog; for Charles blindness was more of an attribute than a handicap.

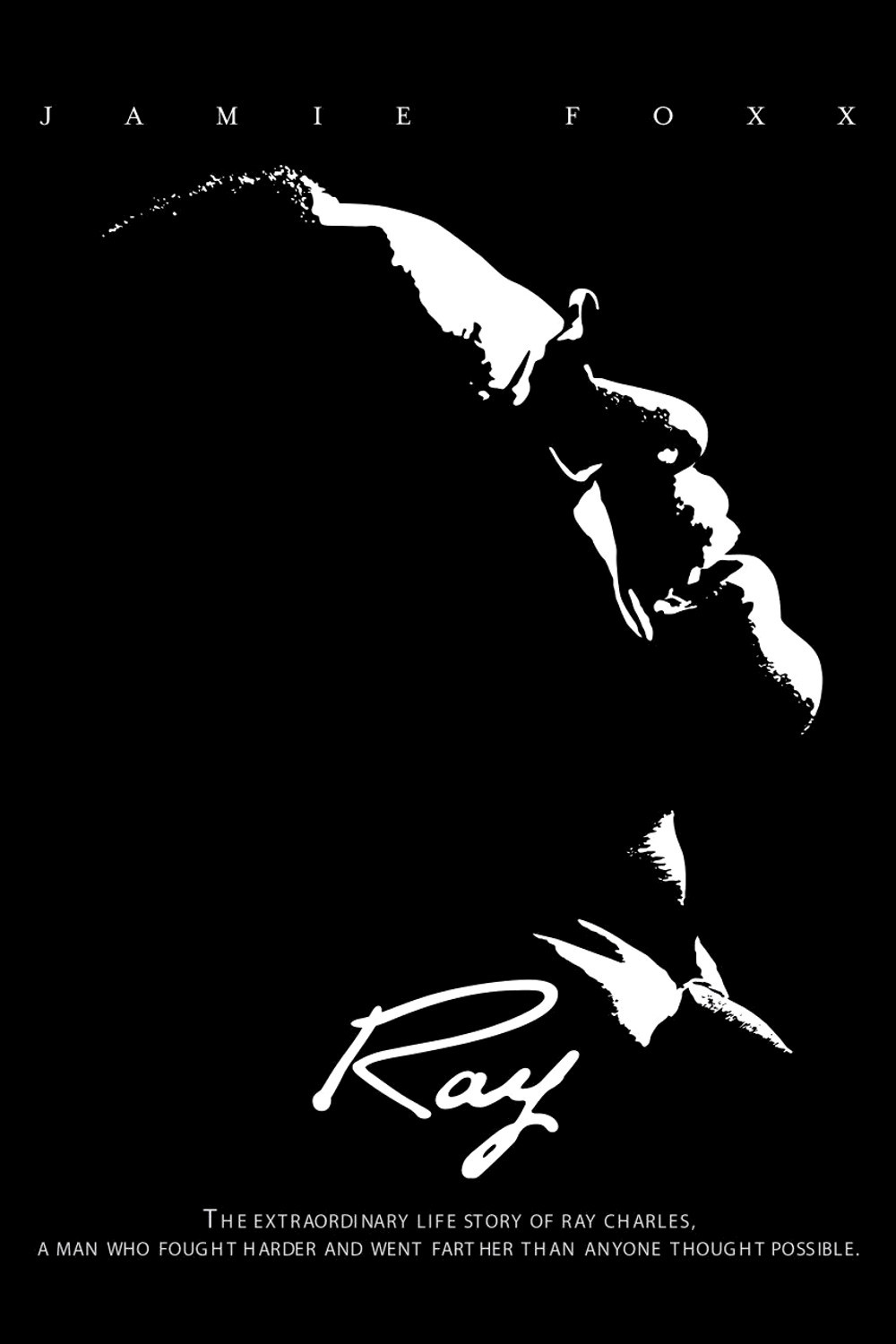

Jamie Foxx suggests the complexities of Ray Charles in a great, exuberant performance. He doesn’t do the singing — that’s all Ray Charles on the soundtrack — but what would be the point? Ray Charles was deeply involved in the project for years, until his death in June, and the film had access to his recordings, so of course it should use them, because nobody else could sing like Ray Charles.

What Foxx gets just right is the physical Ray Charles, and what an extrovert he was. Not for Ray the hesitant blind man of cliche feeling his way, afraid of the wrong step. In the movie and in life, he was adamantly present in body as well as spirit, filling a room, physically dominant, interlaced with other people. Yes, he was eccentric in his mannerisms, especially at the keyboard; I can imagine a performance in which Ray Charles would come across like a manic clown. But Foxx correctly interprets the musician’s body language as a kind of choreography, in which he was conducting his music with himself, instead of with a baton. Foxx so accurately reflects my own images and memories of Charles that I abandoned thoughts of how much “like” Charles he was and just accepted him as Charles, and got on with the story.

The movie places Charles at the center of key movements in postwar music. After an early career in which he seemed to aspire to sound like Nat “King” Cole, he loosened up, found himself, and discovered a fusion between the gospel music of his childhood and the rhythm & blues of his teen years and his first professional gigs. The result was, essentially, the invention of soul music, in early songs like “I Got a Woman.”

The movie shows him finding that sound in Seattle, his improbable destination after he leaves his native Georgia. Before and later, it returns for key scenes involving his mother Aretha (Sharon Warren), who taught him not to be intimidated by his blindness, to dream big, to demand the best for himself. She had no education and little money, but insisted that he attend the school for the blind, which set him on his way. He heads for Seattle after hearing about the club scene, but why there and not in New York, Kansas City, Chicago or New Orleans? Certainly his meeting with the Seattle teenager Quincy Jones was one of the crucial events in his life (as was his friendship with the dwarf emcee Oberon, played by Warwick Davis, who turns him on to pot).

The movie follows Charles from his birth in 1930 until 1966, when he finally defeats his heroin addiction and his story grows happier but also perhaps less dramatic. By then he had helped invent gospel, had moved into the mainstream with full orchestration, had moved out of the mainstream into the heresy of country music (then anathema to a black musician) and had, in 1961, by refusing to play a segregated concert in Georgia, driven a nail in the corpse of Jim Crow in the entertainment industry.

In an industry that exploits many performers, he took canny charge of his career, cold-bloodedly leaving his longtime supporters at Atlantic Records to sign with ABC Paramount and gain control of his catalog. (It’s worth noting that the white Atlantic owners Ahmet Ertegun and Jerry Wexler are portrayed positively, in a genre that usually shows music execs as bloodsuckers.) Charles also fathered more children than the movie can tell you about, with more women than the movie has time for, and yet found the lifelong love and support of his wife, Della Bea Robinson (Kerry Washington).

The film is two and a half hours long — not too long for the richness of this story — but to cover the years between 1966 and his death in 2004 would have required more haste and superficial summary than Hackford and his writer, James L. White, are willing to settle for. When we leave him, Ray is safely on course for his glory years, although there is a brief scene set in 1979 where he receives an official apology from his home state of Georgia over the concert incident, and “Georgia on My Mind” is named as the state song.

Charles’ addictions were to drugs and women. He only beat drugs, but “Ray” is perceptive and not unsympathetic in dealing with his roving ways. Of the women we meet, the most important is his wife Della Bea, played by Washington as a paragon of insight, acceptance and a certain resignation; when one of his lovers dies, she asks him, “What about her baby?” “You knew?” says Charles. She knew everything.

His two key affairs are with Ann Fisher (Aunjanue Ellis), a blues singer, and Margie Hendricks (Regina King), a member of his backup group, the Raelettes. Who knows what the reality was, but in the film we get the sense that Charles was honest, after his fashion, about his womanizing, and his women understood him, forgave him, accepted him and were essential to him. Not that he was easy to get along with during the heroin years, and not that they were saints, but that, all in all, whatever it was, it worked. “On the road,” says Margie, in a line that says more than it seems to, “I’m Mrs. Ray Charles.”

The movie would be worth seeing simply for the sound of the music and the sight of Jamie Foxx performing it. That it looks deeper and gives us a sense of the man himself is what makes it special. Yes, there are moments when an incident in Ray’s life instantly inspires a song (I doubt “What’d I Say?” translated quite so instantly from life to music). But Taylor Hackford brings quick sympathy to Charles as a performer and a man, and we remember that he directed made “Hail! Hail! Rock and Roll,” a great documentary about Chuck Berry, a performer whose onstage and offstage moves more than braced Hackford for this film. Ray Charles was quite a man; this movie not only knows it, but understands it.