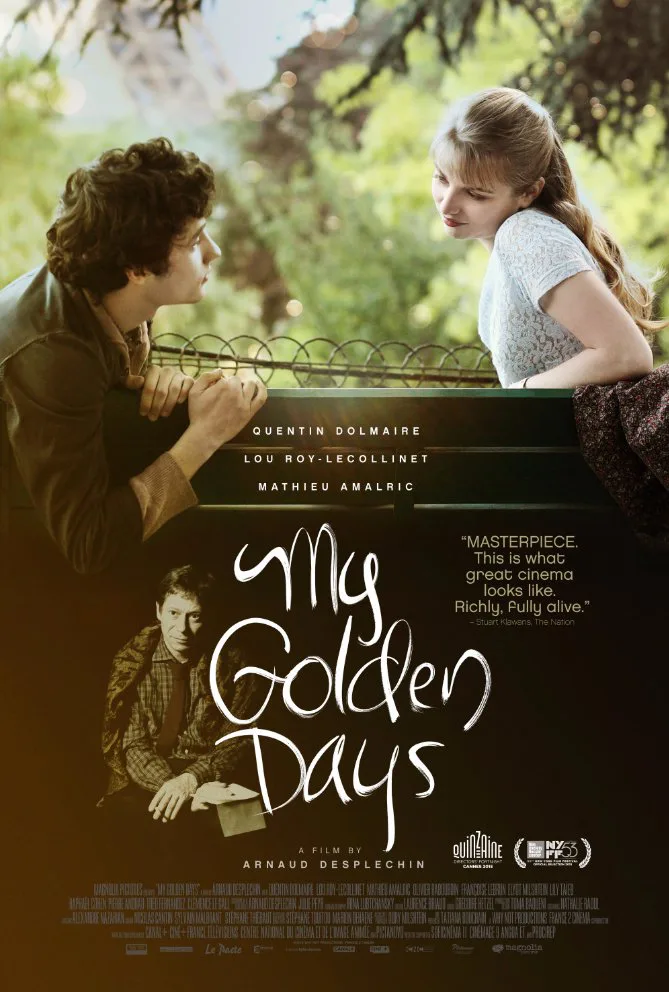

The title of French coming-of-age drama “My Golden Days”—originally named “Trois souvenirs de ma jeunesse,” or “Three Memories of My Youth”—simultaneously is and isn’t a sincere assessment of Paul Dédalus’ memories of adolescence. As an adult, Paul (Mathieu Amalric) recalls his past in fragments—or so he says. Since Paul’s memories are presented as three self-sufficient, narratively unrelated segments, “My Golden Days” primarily concerns Paul’s teenage romance with Esther (Lou Roy-Lecollinet). In fact, Esther and Paul’s relationship monopolizes the film: the other two “memories” that Paul recalls are relatively slight anecdotes, stories that provide a compelling, but inessential backstory for Paul (played by Quentin Dolmaire when Paul is 19 years old). This is the first hint that the film’s American name cannot be strictly trusted.

As our unreliable window into his past, Amalric’s Paul abruptly switches his voiceover narration from the first to the third person. He also warns us and—in the past as well as the story’s present day—tells everyone that he remembers nothing but these three “fragments” with absolute clarity. Paul’s stories are arguably good/happy memories, but they are also full of melancholy, and anxiety. Still, he’s chosen to turn them into miniature oases of time that he can return to at a moment’s notice because of related underlying traumas that writer/director Arnaud Desplechin (“A Christmas Tale,” “Esther Kahn”) thankfully does not fetishize or sappen up with tacky sentimentality. Paul’s stories are the ripples created by Paul’s actions. He is never not in control/to blame for his life, a tough-minded mentality that inspires rich, personal dialogue and characterizations.

Like Bernardo Bertolucci’s enthralling “The Dreamers” before it, “My Golden Days” humanely treats adolescence as a revolutionary period that is at least partly motivated, though not entirely explained by, teenagers’ disdain for parents, teachers, and other authority figures. The first of Paul’s three memories actively hints at what he’s trying to escape: beatings from his father Abel (Olivier Rabourdin) and manic episodes with mother Jeanne (Cécile Garcia-Fogel). But again, this is Paul’s story: nothing that Paul does in “My Golden Days” can be neatly or exclusively attributed to a previous encounter. When he meets Esther, he doesn’t treat her as a surrogate mother, nor does he change in his attitude towards a slightly older, and relatively benign Abel. Instead, he tosses off considerate self-assessments like “The truth is I don’t see [Abel] because I can’t help [him],” and moves on to the next party, the next book, or just the next scene.

That “and moves on” bit is crucial. Paul’s competing passions frequently make it impossible for him to comfortably support a relationship with Esther, a popular, sexually active 14-year-old that Paul tries to impress—by acting uninterested. Their will-they/won’t-they romantic tension arguably provides “My Golden Days” with its main narrative, but that’s not really what the film is about. Desplechin revels in milieu, and in the clarity of his characters’ expressions. These protagonists’ motives are transparent. They have no reservations about their actions: Paul and Esther frequently develop relationships outside of their own, and insist that their satellite hook-ups are purely sexual. But you can see cracks in their cool facades when they joke and tease each other, like when Paul brushes off a girl by flatly insisting “You’re drunk. You deserve better.” Her flirtatious, matter-of-fact rejoinder is priceless: “You’re wrong. I’m not drunk.”

That kind of evasiveness is essentially why Desplechin’s drama feels so honest. Paul repeatedly insists “I’m fine. I didn’t feel a thing” because his first impulse is to run away, to put up a front, and to keep those inter-personal defenses up when he hears Esther beg him to stay with her (“I get scared when you’re gone”). He’s touched by her letters, but that’s just it: these messages are honest, but they’re also composed, as Desplechin notes by filming Roy-Lecollinet reading her letters to his camera/Paul in head-on, fourth-wall-probing close-ups. Neither Esther nor Paul completely bare their souls in melodramatic breakdowns, though they do cry a couple of times. Desplechin wants viewers to see them as people that protect themselves, and in so doing reveal more than they probably know. These memories do not constitute a world of experience, but rather one world among many. If Desplechin chose to make a sequel to “My Golden Days,” it could easily just be three, or five more isolated vignettes.

Desplechin deserves special praise for severing turning Esther into a disposable foil for Paul’s rich inner life. Roy-Lecollinet does the heavy lifting throughout, but Desplechin dotes on her character, like in the scene where Esther dances self-consciously—but earnestly—at a hash party while The Specials’ “I Can’t Stand It” plays, and Paul watches her move. When you watch Roy-Lecollinet struggle to lose herself in the music, you see her as an active character, one who could never be dismissed as a projection, or as an enigma that Paul must solve. You get the impression that these events are all happening outside of Paul’s head, a remarkable feat given that we’re periodically reminded that we’re watching life through Paul’s eyes. “My Golden Days” exists simultaneously within and outside of its characters’ headspace, a testament to Deplechin’s powers of imaginative sensitivity.