Filmmaker Mike Leigh’s biography of the landscape painter J.M.W. Turner is what critics call “austere”—which means it’s slow and grim and deliberately hard to love—yet it’s fascinating, and the performances and photography are outstanding. Leigh, the writer and director of such classics as “Naked” and “Secrets and Lies,” usually tells stories set in the present day, often of a more urban character. His notable exceptions, such as the outstanding “Topsy-Turvy” and this movie, require him to work in a somewhat different vein, and be more attentive to composition and atmosphere and period-accurate psychology; but it’s just as compelling a mode, because Leigh’s emotionally reserved nature comes through more strongly, and seems attuned to his buttoned-up, often repressed characters, who shove negative thoughts way down inside themselves, practically to the bottoms of their feet, and soldier on.

The film’s title character is one of many such characters in “Mr. Turner.” Timothy Spall plays the Cockney painter, who imbued often outwardly unremarkable panoramas with an intensely spiritual feeling that’s intriguingly hard to match up with the man we see before us onscreen. Often described as the “painter of light,” Turner was part of the Romantic school of painters, whose work eventually led, on visual art’s slowly unfolding timeline, to the Impressionists. The film is appropriately fascinated by light and color and what it takes to create or re-create them. Turner, who’s a stiff when it comes to talking about everything else in life, can go on forever about light. He listens closely when his Scottish polymath cousin Mary Somerville (Lesley Manville) schools him on the magnetic properties of violet, or when his father (Paul Jesson), who travels the world buying his son paint, warns him, “Ultramarine’s going up a guinea a bladder.”

I say Turner’s a “stiff” when he’s not talking about art, but that’s an understatement. When not painting or discussing painting, much of his behavior is socially inept, insensitive, often unfathomably inappropriate, to the point where you wonder if he has some sort of condition. He seems not to be in control of his impulses, much more so than more functional people around him. At times he seems—to put it in a modern way—to be not quite wired right. The combination of his awe-inspiring talent and the acclaim it brought him explains, at least partly, why almost nobody calls him on his strangeness or piggishness. To be fair, though, the 1829 death of his father, an event that occurs early in this movie, might have spurred a lot of the behavior that Leigh explores; depression tends to amplify one’s personality as surely as intoxicants might. We see Turner going to a brothel and asking to draw a prostitute, then weeping inconsolably, then having his way with his housekeeper (whose expression indicates that this is not an uncommon occurrence, and is in fact one aspect of their complicated relationship). He is a shattered man.

We also see Turner interacting with his colleagues, many of them landscape painters nearly as famous, at a gallery show, where he walks around inspecting the layout of the gallery, telling a painter friend that a woman’s leg in a panorama could use a bit of highlight, and then startling everyone by painting a single daub of red in the middle of an intricately finished landscape painting—an act that another painter interprets as a declaration of war on whatever cliches the show embodies. It’s in this latter sequence that “Mr. Turner” most distinguishes itself from other films about art and artists, indeed from most screen biographies.

Like Leigh’s “Topsy-Turvy,” which showed the world of Gilbert and Sullivan almost exclusively through their eyes, and the eyes of their performers and collaborators, “Mr. Turner” understands creative people on every conceivable level, and translates that understanding with a deftness rarely seen outside of astute documentaries about creative people. To watch it is to feel as though you’re a part of its world, talking shop with the painters, experiencing tiny fluctuations in received wisdom and sudden changes of artistic direction that can only be sensed by professionals who are plugged into their art form, and completely in command of their talents.

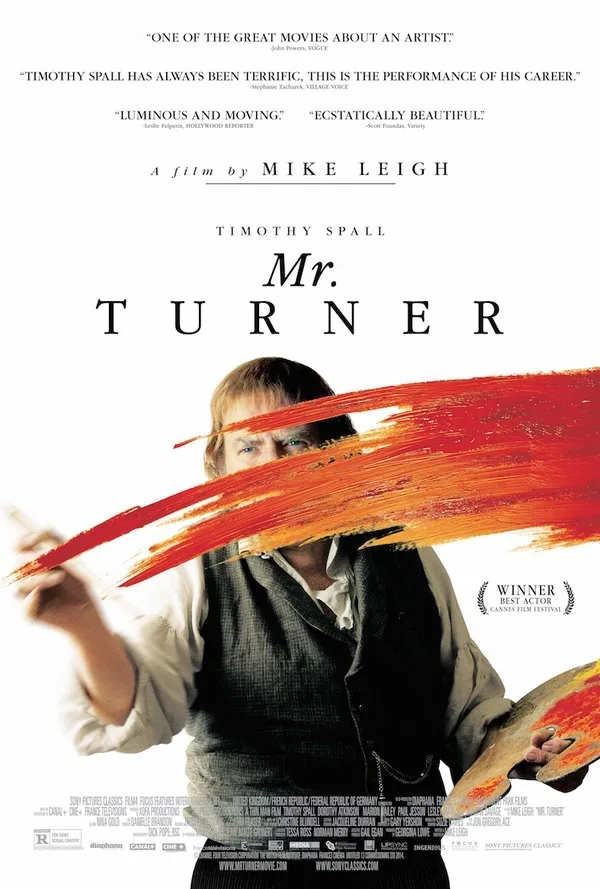

That the performances are excellent will come as no surprise to Leigh fans. Spall, who’s had a remarkably varied career, adds another fine portrait to his own actor’s gallery with Turner, a character who’s impossible to fully fathom (as if you’d want to!) and even more impossible to approve of. He can be high-handed, brusque, oblivious. But there’s something immensely sad about him, and you can sense it most strongly during moments like the one pictured at the top of this page, when he’s seen from a distance, from head to toe, moving through the sorts of landscapes that he himself might paint. These images, photographed by Leigh’s regular cinematographer Dick Pope, express the essence of a phrase used by Manville, “the interconnectedness of all things.”