“Mifune” is the latest work with the imprimatur of Dogma ’95, a group of Danish filmmakers who signed a cinematic “vow of chastity”–reserving poverty and obedience, apparently, for TV directors. Dogma films are encouraged to use natural light and sound, real locations, no props or music brought in from outside, hand-held cameras and “no directorial touches,” as if the auteur theory was shamelessly immodest. Of the Dogma films I have seen (“The Idiots,” “The Celebration“) and the Dogma wannabe “julien donkey-boy,” it is the most fun and the least dogmatic. With just a few more advances–like props, sets, lighting, music and style–the Dogma crowd will be making real movies.

Only kidding. But in truth, Dogma ’95 is as much publicity as conviction, and its films contain more, not less, directorial style. Like the American indie movement, it calls for small budgets and unsprung plots, but that’s not a creed, it’s a strategy for making a virtue of necessity. That the Dogma films have been good and interesting is encouraging, but a coincidence.

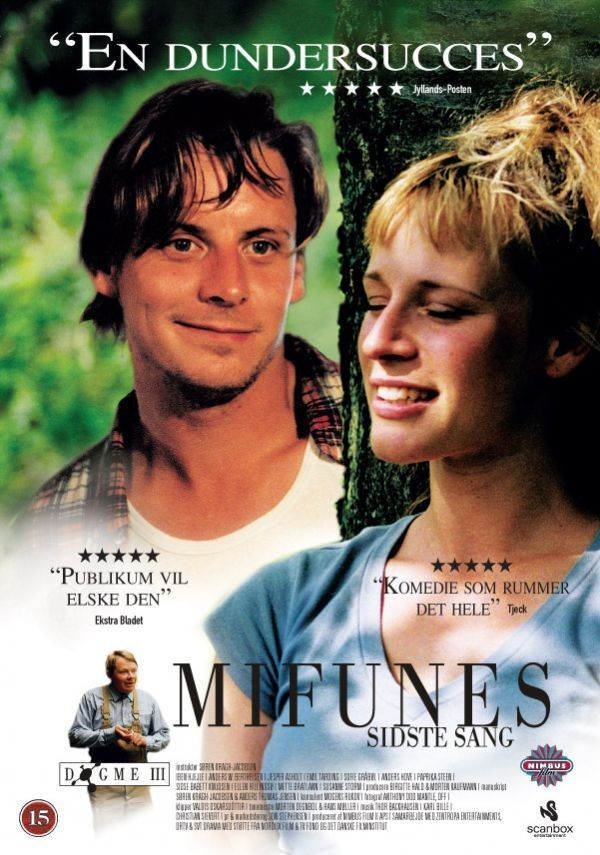

The story of “Mifune” breaks down no barriers but is in the tradition of offbeat romantic comedy, and one can imagine it being remade by Hollywood with Jeff Daniels as the hero, Martin Short as the retarded brother, and Angelina Jolie as the hooker. It is a “commercial” story, and all the more entertaining for being so, but Soren Kragh-Jacobsen‘s low-rent version has a freshness and spontaneity that the Hollywood version would probably lose. There’s something about ground-level filmmaking that makes an audience feel a movie is getting away with something.

The story begins with the wedding of Kresten (Anders W. Berthelsen) and Claire (Sofie Grabol). If the eye contact between Kresten and Claire’s sexy mother is any indication, this marriage might have soon grown very complicated, but Kresten’s past catches up with him and dooms the marriage (not, luckily for Claire, before a wedding night that seems to set Guinness records). Kresten learns that his father has died, and he has avoided telling his wife and snotty in-laws about his family’s ramshackle farm, his retarded brother or his mother who hung herself on “one of the oldest trees in Denmark.” (“He grew up,” observes A. O. Scott, “in the Danish translation of a Tennessee Williams play.”) Kresten returns to the farm, which is a rundown shambles with water damage and animals making free use of the house and finds his brother Rud (Jesper Asholt) drinking under the table that bears the father’s corpse. What to do? Rud cannot take care of himself, the farm is falling to pieces, and this is not the kind of situation he can bring Claire into. Desperate, Kresten hires a housekeeper named Liva, played by Iben Hjejle (she plays Laura, the lost love, in “High Fidelity“). Liva is desperate, too; we learn she was a hooker, is being pursued by an angry pimp and receives alarming phone calls.

At this point in the story, not even the most stringent application of Dogma vows can prevent the director and his audience from hurtling confidently toward the inevitable development in which Kresten and Liva fall in love and form a sort of instant family with Rud as honorary child. Dogma forbids genre conventions, but this story is made from the ground up of nothing else–and more power to it.

If the story is immensely satisfying in a traditional way, the style has its own delights. Kragh-Jacobsen feels free to meander. Every single scene doesn’t have to pull its weight and move the plot marker to the next square. Asides and irrelevant excursions are allowed. Characters arrive at conclusions by a process we can follow on the screen, instead of signaling us that they are only following the script. And there is an earthiness to the unknown actors, especially Asholt as Rud, that grounds the story in the infinite mystery of real personalities.

Watching “Mifune” and the other Dogma films (except for “julien,” which is more of an exercise in video art), we’re taught a lesson. It’s not a new lesson; John Cassavetes taught it years ago and directors as various as Mike Leigh and Henry Jaglom demonstrate it. It has to do with the feel of a film, regardless of its budget or the faces in the cast. Some films feel free, and others seem caged. Some seem to happen while we watch, and others seem to know their own fates. Some satisfy by marching toward foregone conclusions, and others (while they may arrive at the same place) seem surprised and delighted by how they turn out.

“Mifune” is like a lesson in film-watching. If you see enough films like this, you learn to be suspicious of high-gloss films that purr along mile after mile without any bumps. If a film like this were a car and it stalled, you could go under the hood with a wrench. When fancy films stall, you need a computer expert.