Remember that Orson Welles himself didn’t always look like Orson Welles. He was a master of makeup and disguise, and even when appearing in the first person, liked to use a little putty to build up a nose he considered a tad too snubbed. The impersonation of Welles by Christian McKay in “Me and Orson Welles” is the centerpiece of the film, and from it, all else flows. We can almost accept that this is the Great Man.

Twenty-four years after his death at 70, Welles is more than ever a Great Man. There is something about his manner, his voice and the way he carries himself that evokes greatness, even if it is only his own conviction of it. He is widely thought of as having made one masterpiece, “Citizen Kane” (1941) and several other considerable films, but flaming out into uncompleted projects and failed promise. Yet today even such a film as “The Magnificent Ambersons” (1942), with its ending destroyed by the studio, often makes lists of the greatest of all time.

Oh, he had an ego. He once came to appear at Chicago’s Auditorium Theatre. A snowstorm shut down the city, but he was able to get to the theater from his nearby hotel. At curtain time, he stepped before the handful of people who had been able to attend. “Good evening,” he said. “I am Orson Welles — director, producer; actor; impresario; writer; artist; magician; star of stage, screen and radio, and a pretty fair singer. Why are there so many of me, and so few of you?”

Richard Linklater’s “Me and Orson Welles” is one of the best movies about the theater I’ve ever seen, and one of the few to relish the resentment so many of Welles’ collaborators felt for the Great Man. He was such a multitasker that while staging his famous Mercury Theatre productions on Broadway, he also starred in several radio programs, carried on an active social life and sometimes napped by commuting between jobs in a hired ambulance. Much of the day for a Welles cast member was occupied in simply waiting for him to turn up at the theater.

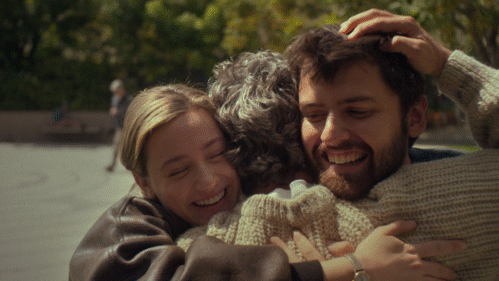

Most viewers of this film will not necessarily know a lot about Welles’ biography. There’s no need to. Everything is here in context. The film involves the Mercury’s first production, a “Julius Caesar” set in Mussolini’s Italy. It sees this enterprise through the eyes of Richard Samuels (Zac Efron), a young actor who is hired as a mascot by Welles, and somehow rises to a speaking role. He is star-struck and yet self-possessed and emboldened by a sudden romance that overtakes him with a Mercury cohort, Sonja Jones (Claire Danes).

The film is steeped in theater lore. The impossible hours, the rehearsals, the gossip, the intrigue, the hazards of stage trap doors, the quirks of personalities, the egos, the imbalance of a star surrounded entirely by supporting actors — supporting on stage and in life.

Many of the familiar originals are represented here, not least Joseph Cotton (James Tupper), who co-starred with Welles in “Citizen Kane” and “The Third Man.” Here is John Houseman (Eddie Marsan, not bulky enough but evocative), who was Welles’ long-suffering producer. And the actor George Coulouris (Ben Chaplin), who played Mr. Thatcher in “Kane.” All at the beginning, all in embryo, all promised by Welles they would make history. They believed him, and they did.

McKay summons above all the unflappable self-confidence of Welles, a con man in addition to his many other gifts, who was later able to talk actors into appearing in films that were shot over a period of years, as funds became available from his jobs in other films, on TV, on the stage and in countless commercials (“We will sell no wine before its time”). Self-confidence is something you can’t act; you have to possess it, and McKay, in his first leading role, has that in abundance.

He also suggests the charisma that swept people up. People were able to feel that even in his absence; I recall having lunch several times at the original Ma Maison in Beverly Hills, where no matter who I was interviewing (once it was Michael Caine), the conversation invariably came around to a mysterious shadowy figure dining in the shade — Welles, who ate lunch there every single day.

Efron and Danes make an attractive couple, both young and bold, unswayed by Welles’ greatness but knowingly allowing themselves to be used by it. Linklater’s feel for onstage and backstage is tangible, and so is his identification with Welles. He was 30 when he made his first film, Welles of course 25, both swept along by unflappable fortitude. “Me and Orson Welles” is not only entertaining but an invaluable companion to the life and career of the Great Man.