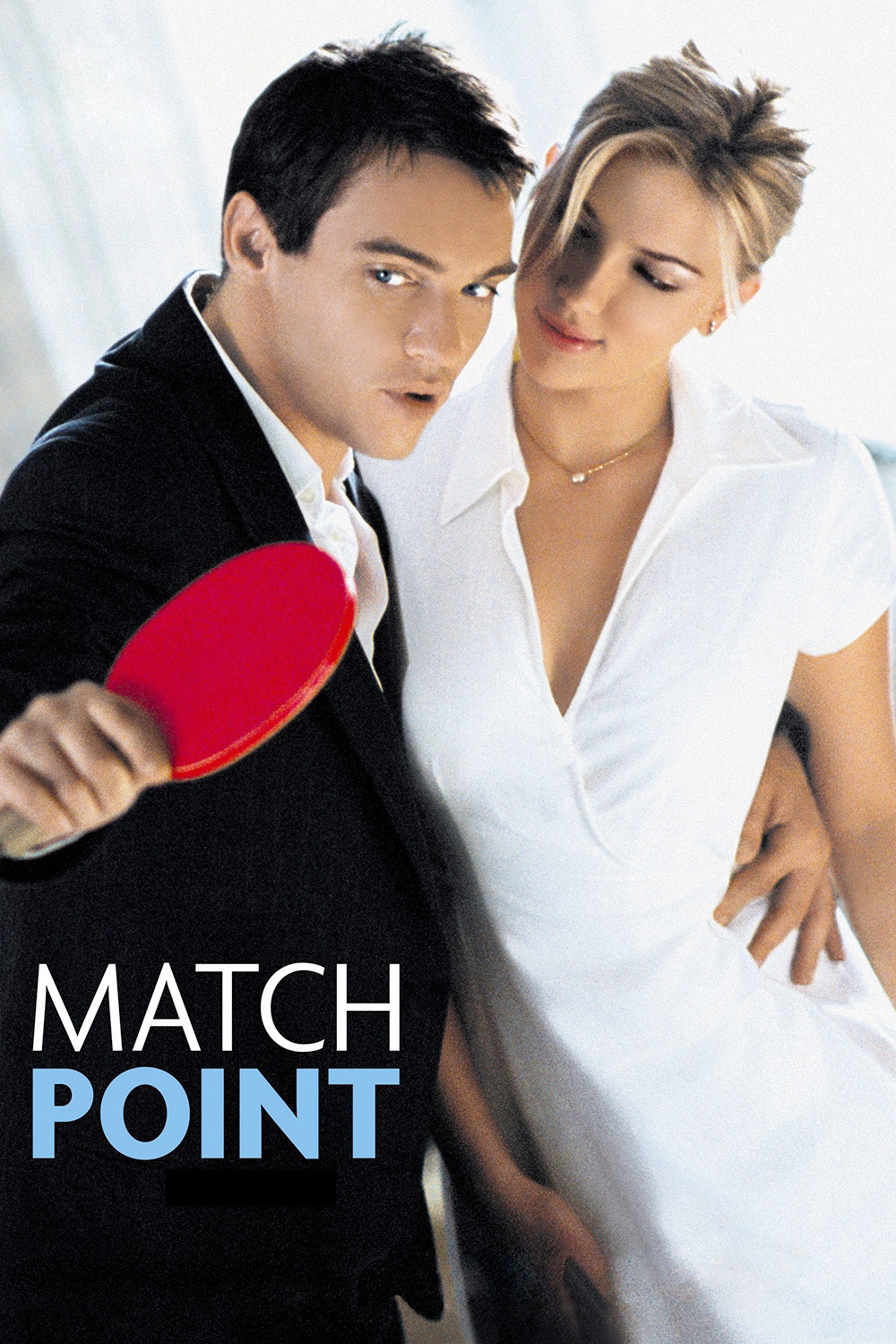

One reason for the fascination of Woody Allen‘s “Match Point” is that each and every character is rotten. This is a thriller not about good versus evil, but about various species of evil engaged in a struggle for survival of the fittest — or, as the movie makes clear, the luckiest. “I’d rather be lucky than good,” Chris, the tennis pro from Ireland, tells us as the movie opens, and we see a tennis ball striking the net – it is pure luck which side it falls on. Chris’ own good fortune depends on just such a lucky toss of a coin.

The movie, Allen’s best since “Crimes and Misdemeanors” (1989), involves a rich British family and two outsiders who hope to enter it by using their sex appeal. They are the two sexiest people in the movie — their bad luck, since they are more attracted to each other than to their targets in the family. Still, as someone once said (Robert Heinlein if you must know), money is a powerful aphrodisiac. He added however, “flowers work almost as well.” Not in this movie, they don’t.

The movie stars Jonathan Rhys-Meyers as Chris, a poor boy from Ireland who was on the tennis tour and now works in London as a club pro. He meets rich young Tom (Matthew Goode), who takes a lesson, likes him, and invites him to attend the opera with his family. During the opera, Tom’s sister Chloe (Emily Mortimer) looks at Chris once with interest and the second time with desire. Chris does not need to have anything explained to him.

Tom’s own girlfriend is Nola (Scarlett Johansson), an American who hopes to become an actress or Tom’s wife, not in that order. Tom and Chloe are the children of Alec and Eleanor Hewett (Brian Cox and Penelope Wilton), who have serious money, as symbolized by the country house where the crowd assembles for the weekend. It’s big enough to welcome two Merchant-Ivory productions at the same time.

Chloe likes Chris. She wants Chris. Her parents want Chloe to have what she wants. Alec offers Chris a job in “one of my companies” — always a nice touch, that. Tom likes Nola, but to what degree, and do his parents approve? All is decided in the fullness of time, and now I am going to become maddeningly vague in order not to spoil the movie’s twists and turns, which are ingenious and difficult to anticipate.

Let us talk instead in terms of the underlying philosophical issues. To what degree are we prepared to set aside our moral qualms in order to indulge in greed and selfishness? I have just finished re-reading The Wings of the Dove, by Henry James, in which a young man struggles heroically with just such a question. He is in love with a young woman he cannot afford to marry, and a rich young heiress is under the impression he is in love with her. The heiress is dying. Everyone advises him he would do her a great favor by marrying her, and after her death, inheriting her wealth, he could afford to marry the woman he loves. But isn’t this unethical? No one has such moral qualms in Allen’s film, not even sweet Chloe, who essentially has her daddy buy Chris for her. The key question facing the major players is: Greed, or lust? How tiresome to have to choose.

Without saying why, let me say that fear also enters into the equation. In a moral universe, it would be joined by guilt, but not here. The fear is that in trying to satisfy both greed and lust, a character may have to lose both, which would be a great inconvenience. At one point this character sees a ghost, but this is not Hamlet’s father, crying for revenge; this ghost drops by to discuss loopholes in a “perfect crime.”

When “Match Point” premiered at Cannes last May, the critics agreed it was “not a typical Woody Allen film.” This assumes there is such a thing. Allen has worked in a broad range of genres and has struck a lot of different notes, although often he uses a Woody Figure (preferably played by himself) as the hero. “Match Point” contains no one like Woody Allen; is his first film set in London; is constructed with a devious clockwork plot that would distinguish a film noir, and causes us to identify with some bad people. In an early scene, a character is reading Crime and Punishment, and during the movie, as during the novel, we are inside the character’s thoughts.

The movie is more about plot and moral vacancy than about characters, and so Allen uses type-casting to quickly establish the characters and set them to their tasks of seduction, deception, lying and worse. Meyers has a face that can express crafty desire, which is not pure lust but more like lust transformed by quick strategic calculations. Matthew Goode, as his rich friend, is clueless almost as an occupation. Emily Mortimer plays a character incapable of questioning her own happiness, no matter how miserable it should make her. Scarlett Johansson’s visiting American has been around the block a few times, but like all those poor American girls in Henry James, she is helpless when the Brits go to work on her. She has some good dialogue in the process.

“Men think I may be something special,” she tells Chris.

“Are you?”

“No one’s ever asked for their money back.”

“Match Point,” which deserves to be ranked with Allen’s “Annie Hall,” “Hannah and Her Sisters,” “Manhattan,” “Crimes and Misdemeanors” and “Everyone Says I Love You,” has a terrible fascination that lasts all the way through. We can see a little way ahead, we can anticipate some of the mistakes and hazards, but the movie is too clever for us, too cynical. We expect the kinds of compromises and patented endings that most thrillers provide, and this one goes right to the wall. There are cops hanging around trying to figure out what, if anything, anyone in the movie might have been up to, but they’re too smart and logical to figure this one out. Bad luck.