[Editor’s note: This review contains spoilers.]

There’s one crucial thing that “Looking for Mr. Goodbar” doesn’t make clear: Just because you find Mr. Goodbar doesn’t necessarily mean you were looking for him. The heroine of Judith Rossner’s bestseller was looking. Theresa was turned on to a particular flavor of self-destructive sexual experience, one involving possible danger to herself, and she played a role in bringing about her own death.

In Richard Brooks’s film version, that masochistic impulse isn’t considered as openly. He gives us a Theresa who drinks too much, sleeps around too much, and takes too many drugs — but she seems more of a hedonist than a masochist. She’s looking for a combination of good times, good sex, and a father figure, for psychological reasons the movie makes all too abundantly clear. But she isn’t looking for danger, mistreatment, or death. Maybe Brooks thought audiences would find Rossner’s masochistic heroine too hard to understand. He has rewritten the story, in any event, into a cautionary lesson: Promiscuous young women who frequent pick-up bars and go home with strangers are likely to get into trouble.

Brooks hasn’t improved the story by changing its focus, and he’s distracted from the heart of the narrative by several unnecessary scenes. Theresa’s fantasies, for example, are handled in ways that annoy viewers more than they intrigue them. And her home life — its broadly painted Freudian details right out of soap operas — could have just simply been dropped.

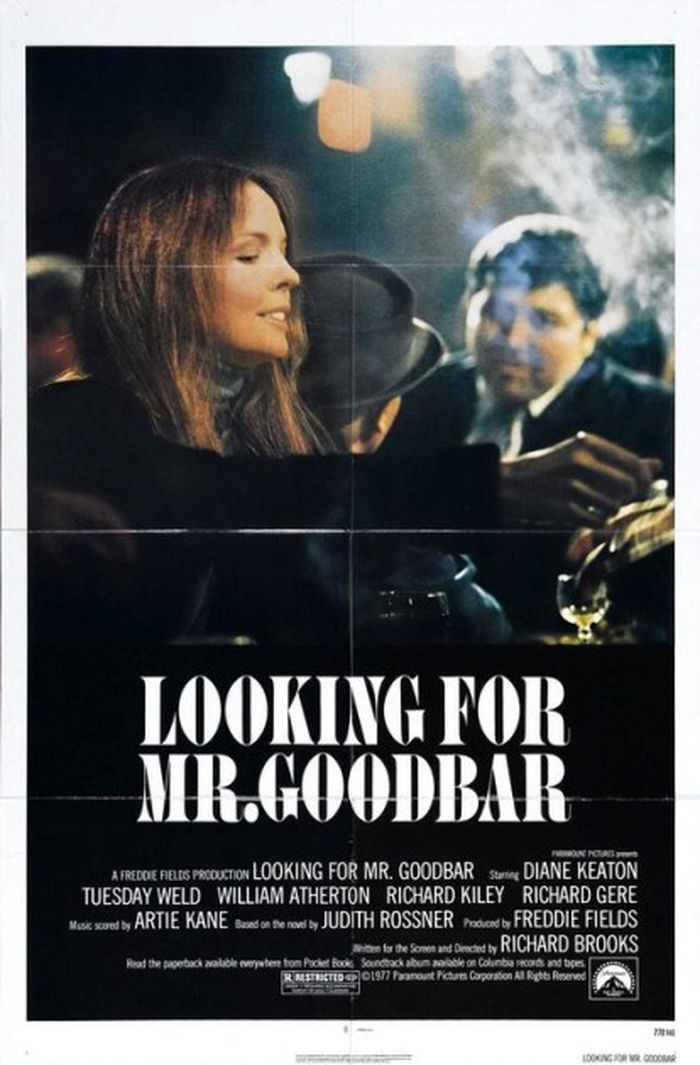

But, all the same, Brooks hasn’t directed a bad picture. “Looking for Mr. Goodbar” is very much worth seeing, particularly for the Diane Keaton performance. And it’s not fair to praise her while damning Brooks (as so many critics have done). Brooks and Keaton must have worked together to create such a great performance; it’s just a shame that it’s surrounded by perhaps half an hour of material that only distracts.

The performance creates a character who would have been unthinkable in the movies of thirty years ago: A young woman who spends her days teaching first grade to a classroom of deaf-mutes and her nights making herself available in singles bars. Women weren’t allowed to be that complicated in the “women’s pictures” that “Mr. Goodbar” has come such a long way from. They were ladies or they were tramps. Now they’re allowed to be both, which has done wonders for the quality of the tramps you meet these days.

Diane Keaton suggests the motivation for her character almost independently from all those heavy-handed scenes in which her father stomps around the living room, and we get flashbacks of her tragic childhood. She suggests that Theresa is driven by a need to communicate on her own terms — and that those terms require her to have an advantage. She’s great in a classroom of deaf-mutes, and great, too, with the men she picks up — men who are inarticulate because of insecurity, cultural short-changing, or too much booze. She delights in working people over verbally — in kidding them, mocking them, putting them down, playing games with them. On the physical level, though, she needs constant reassurance.

This Theresa is a different woman from the Judith Rossner character, but she’s an interesting one. And Keaton plays her wonderfully, with a light touch you’d think would be impossible with this material. She’s always moving. She choreographs every situation, and only eventually do we realize she’s dancing out of the way. Her voice is liquid and funny, tossing off asides because they cut more deeply that way. The performance and the character are fully realized, even in this movie that finds room for so many loose ends and dead ends.

Then there’s that ending that bothers me. On a New Year’s Eve, she makes a fatal decision in choosing the next guy she’s going to take home. We know she’s made the wrong decision because Brooks abandons her point of view to show us a scene in which the guy is established as unbalanced and hostile. But she doesn’t know that and gets killed because she doesn’t. Her lack of knowledge is exactly the issue here: In the book, Theresa might have picked up the guy because she knew he’d be trouble.

What we get (and I quote from someone walking out of the screening ahead of me) is “another one of those movies that are supposed to be all filled with significance because the person gets killed at the end.” What we might have gotten is a movie about a character obsessed, and fascinated, by what the end might be. Even a movie about how she got to be that way.