Although it was not quite his last film, there can be little doubt that “Limelight” was Charlie Chaplin’s farewell. It is also probably his most personal, revealing film. He plays an old clown, Calvero, who was once hailed on the stages of the world as the greatest clown alive. But now Calvero has been forgotten, his art is considered “obsolete,” and he lives by himself in a run-down rooming house. He goes on a toot occasionally to break the monotony. Otherwise, there is nothing but his old scrapbooks and his daydreams.

As symbolical characters go, Calvero stands in pretty well for the Chaplin of 1952 (aside from the fact, of course, that Charlie was worth several dozen million dollars). Chaplin’s previous film, “Monsieur Verdoux” (1947), had not been received well — and represented, indeed, his first critical failure. His personal life bad been plagued by lawsuits and witch hunts, and it is sad to say that when “Limelight” opened in American theaters is was actually picketed by those who thought Chaplin was a Communist, or at least some sneaky kind of pinko.

He never had anything to do with any political party, of course, and in its own way “Limelight” considers what must have really been on Chaplin’s mind in 1952. He had been, at one time not so many years before, the world’s most popular entertainer. It was said that the Little Tramp was the most familiar character ever invented. But now all that was behind him.

What comes through most clearly in “Limelight,” however, is that Chaplin had come to terms with his life. The character he plays doesn’t miss the limelight, not really, and he had not become bitter just because of his recent hard times. He saves a young ballet dancer (Claire Bloom) from suicide and nurses her back to a stage career with his own unshakable optimism. His religion is the stage, but he doesn’t need an audience in order to practice it (and some of the film’s best scenes are his daydreams of stage performances that never were, or maybe never will be).

Like several of Chaplin’s later films, “Limelight” has stretches of sentimentality. I don’t hold that against it; when the clown Calvero suffers a heart attack during his final performance, and then asks to be carried onstage in a drum to take his bow anyway, sentimentality is at work, yes, but a kind of sentimentality that grows out of the hammy, sincere character Chaplin has created.

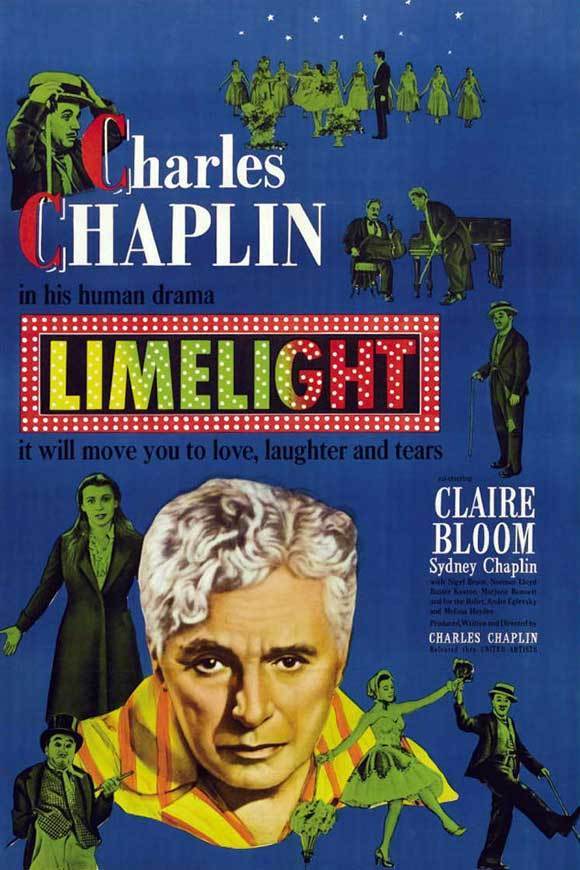

If “Limelight” as a whole is Chaplin’s farewell, then that final vaudeville act is surely his farewell to slapstick. It is a perfect, hilarious gem; he teams up with Buster Keaton to do a piano-violin duet that runs into small problems like a smashed violin and an overstrung piano. His final exit — and then his last request to have his couch carried to the wings, so that he can watch Miss Bloom dance — is perhaps not so much sentimentality as an expression of his belief that if all things must end, then at least they should end gracefully.

NOTE: “Limelight,” like all of Chaplin’s earlier films, was originally shot in the screen ratio of 4 to 3 (which is to say that the picture was 1.33 feet wide for every foot of height). This classic ratio, the so-called “Golden Frame,” has been replaced since the mid-1950s with various ratios in which the screen is wider in relation to height.

Since every shot was conceived with the 4 to 3 ratio in mind, any other projection ratio would, of course, undermine the director’s original intentions and his sense of visual composition and balance. Occasionally such films as “Gone with the Wind” have been “adapted” to a wider screen ratio, with unhappy results. I am very happy to report that for the engagement of “Limelight,” the Carnegie has obtained and is using the correct equipment to project the “Golden Frame.” I’m told the Carnegie is the only theater in the country — including New York — showing the Chaplin festival in the proper screen ratio.