Gus Van Sant has made three movies in which the camera follows young men as they wander toward their deaths. All three films resolutely refuse to find a message in the deaths. No famous death can take place in our society without being endlessly analyzed by experts, who find trends, insights, motives and morals with alarming facility. It’s brave of Van Sant to allow his characters to simply wander off, in John Webster’s words, “to study a long silence.”

In “Gerry” (2003), death is accidental, caused by carelessness. Two friends fecklessly wander into a desert, get lost, and don’t get found. In “Elephant” (2003), death is preceded by murder, and is deliberate but pointless. Two friends carry out a plan to kill students and teachers at their high school, and then they, too, are shot. Now in “Last Days,” death is a condition that overtakes a character as he mumbles and stumbles into the final stage of drug addiction.

These deaths are not heroic or meaningful, and although they may be tragic they lack the stature of classical tragedy. They are stupid and careless, and in “Elephant” they are monstrous, because innocent lives are also taken. If Van Sant is saying anything (I am not sure he is), it’s that society has created young men who do not live as if they value life.

“Last Days” is dedicated to the suicide of Kurt Cobain, who led the band Nirvana, influential in the creation of grunge rock. Grunge as a style is a deliberate way of presenting the self as disposable. In a disclaimer that distances itself from Cobain with cruel precision, the movie says its characters are “in part, fictional.”

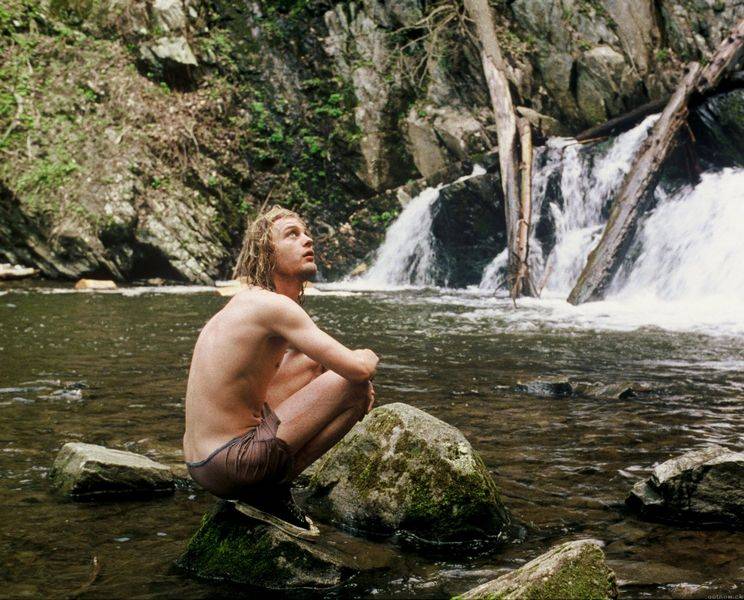

The movie concerns a singer named Blake, who wanders about a big stone house in a wet, gloomy forest area. The first scenes show him throwing up, stumbling down a hillside to a stream, bathing himself, drying his clothes at a campfire, and, in the middle of the night, singing “Home on the Range.” The movie seems unwilling to look at his face very clearly; it is concealed by lanky hair and a hooded coat, and the camera prefers long shots to closeups. We notice that he is wearing the sort of wrist tag you get in a hospital. Blake walks aimlessly through the house, prepares meals (Cocoa Puffs, macaroni and cheese), and listens without comment as people talk to him in person and on the phone.

They’re worried about him. Kim Gordon of Sonic Youth plays a woman who asks him, “Do you talk to your daughter? Do you say I’m sorry that I’m a rock ‘n’ roll cliche?” No answer. “I have a car waiting, and I want you to come with me.” No answer. A detective (Ricky Jay) turns up, cannot find Blake (who hides in the woods), and relates an anecdote about a magician who could catch a bullet in his teeth (most of the time). A musician turns up and wants Blake’s help with a song he is writing about a girl he left behind in Japan. A (real) Yellow Pages salesman (Thadeus A. Thomas) turns up and tries to sell Blake an ad. Harmony Korine turns up (all the characters have the same names as the actors) and talks about playing Dungeons & Dragons with Jerry Garcia.

None of this interests Blake. One night he wanders into a nearby town, into a bar, and out of the bar again. No doubt some of the people in the bar know he is a famous rock star, but his detachment is so complete it forms a wall around him; you look at him, and you know nothing is happening there.

There is a moment at the house when some friends are about to leave, and one man pauses and looks for a long time as Blake, seen indistinctly through the windows of a potting shed, moves aimlessly. That is where his body will be found in the morning. In a curious coda to such a minimalist film, Van Sant shows Blake’s ghostly image leaving his body and ascending, not by floating up to heaven, but by climbing — using the frames of a window as a ladder.

“Last Days” is a definitive record of death by gradual drug exhaustion. After the chills and thrills of “Sid & Nancy” and “The Doors,” here is a movie that sees how addicts usually die, not with a bang but a whimper. If the dead had it to do again, they might wish that, this time, they’d at least been conscious enough to realize what was happening.