One of the more welcome pleasures of “Landline” is that it takes place in 1995, right before mobile phones began their siege upon the general populace. That means the Manhattan dwellers in the movie are forced to actually talk to one another to relay information instead of being constantly enraptured by the presence of a glowing orb in their hands. As someone who has grown weary of watching actors regularly squint at text messages and caller IDs in every contemporary movie, I appreciate the opportunity to be placed in a wayback machine and taken to a not-too-distant past when no hairdo was too big, Natalie Merchant warbled about the weather, “Mad About You” was must-see TV and then-first lady Hillary Clinton delivered her image-defining Beijing speech on women’s rights in a righteous powder-pink suit.

Alas, that last piece of nostalgia might be too soon for some.

But “Landline,” a forlornly funny and emotionally bruising dramedy that rarely misses an opportunity to reveal humans as the flawed and occasionally awful beings that they are, is more interested in the lack of communication that happens among family members and how secrets can fester and turn toxic when they aren’t shared. All too often what is said is less important than what isn’t, especially when the suspicion of infidelity hangs heavy in the air.

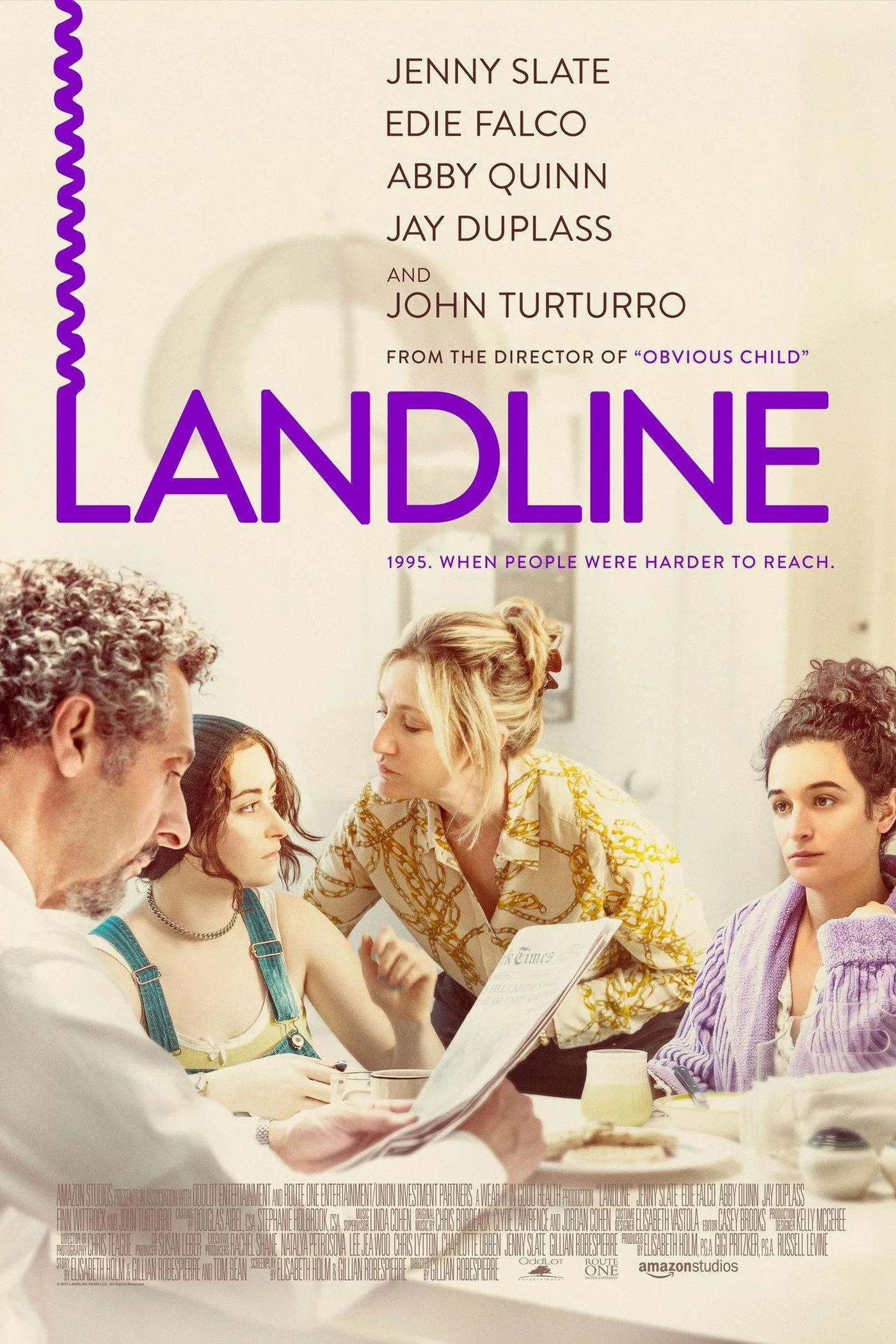

The Sundance breakout has a lot going for it. Topping the list for this darkly droll dissection of dysfunctionality is the reunion of actress Jenny Slate with her “Obvious Child” director Gillian Robespierre and producer Elisabeth Holm, who co-wrote the script that tries to do for divorce what their previous effort did for abortion. That is, demonstrating how such difficult choices can be the right personal decisions for those involved.

And kudos for casting Edie Falco (I so miss “Nurse Jackie”) and John Turturro (I so miss “The Night Of”) as Pat and Alan Jacobs, parents of Slate’s nervous 20-something bride-to-be Dana and newcomer Abby Quinn’s rebellious 17-year-old Ali. They ground the story with more adult matters—namely, the deflated state of their marriage. She’s a Type-A bigshot at the EPA. He’s a mild-mannered ad copy writer and a mediocre wannabe playwright who strives to make art. They reminisce about when they saw Lenny Bruce on their first date and going to Studio 54 when Pat was pregnant. But whatever affection they once had for one another has been overwhelmed by concern for their daughters and disappointment in one another.

Sullen, sulky and too cool for school, Quinn is quite a find, a perfect foil to chatty, scatter-brained Slate. She stealthily redefines the condition known as “senior slump” by not just simply skipping classes but also staying out all night at raves, snorting heroin and consuming alcohol, having sex with her “not a boyfriend,” hanging out with the wrong crowd and perfecting her caustic put-downs. But matters take a serious turn when Ali stumbles upon a floppy disc containing erotic poetry written by her father that gives every indication that he is cheating on her mother.

He is not the only one with a wandering eye. In the very first scene, Dana and fiancé Ben (Jay Duplass, cuddly yet not exactly studly) try to add spice to their love life by having “woodland sex” against a tree trunk. “Is this good,” he inquires mid-act. “No,” she replies while swatting away spiders. We later learn they regularly shower together in their shared apartment although these days it is more a matter of hygiene than hanky panky. That Ben decides to pee on the poison ivy rash on Dana’s leg does not heighten the experience.

Therefore, it is not surprising that Dana falls for the come-ons provided by a hunky former college chum who shows up at a party and is summarily seduced on a park bench. Taking a page out of the “Seinfeld” handbook, they also meet again at a matinee showing of a Nazi documentary where he delivers a rather satisfying bout of oral sex. (Question: Why does movie lovemaking rarely take place in a bed?)

All these matters come to a head, some in more satisfying ways than others. I was not fond of how Slate’s character is regularly humiliated for laughs, whether at work (she calls in sick and they don’t know who she is) or when she indulges her sudden whims (she gets an eyebrow ring that, of course, gets infected). I guess such behavior is de rigueur in the post-“Girls” female landscape but too often such moments just feel like slapstick gone mean. But the fact that Dana and Ali, who previously only shared a penchant for sniping at each other, bond as sisters over their father’s potential deceptions actually feels real and provides the audience with closure. When they eventually bring their mom into the fold, it results in a true winning trifecta of female fortitude.

“Landline” might not bring back Dustbusters or revive Lorena Bobbitt as a go-to reference for stand-ups, but it leaves behind a lingering grace note about family matters that befits any era.