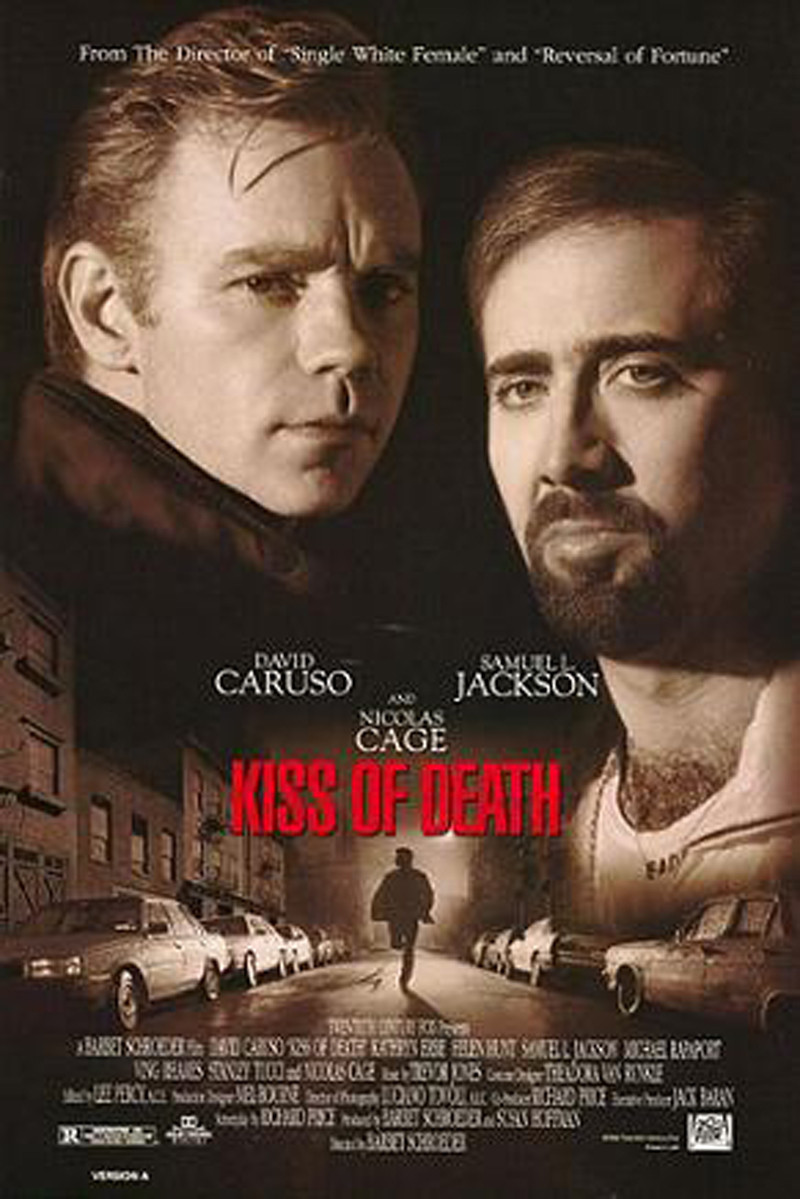

“Kiss of Death” is a hard-boiled crime movie featuring first-time leading man David Caruso, from TV’s “NYPD Blue,” opposite Nicholas Cage as the weirdest villain since Dennis Hopper slithered into “Blue Velvet.” The direction is by Barbet Schroeder (“Reversal of Fortune“), the screenplay is by novelist Richard Price (Clockers), it’s a loose remake of the 1947 movie where Richard Widmark pushed the wheelchair down the stairs, and with a pedigree like that it shouldn’t be disjointed and uncompelling, but it is.

It’s about professional car thieves in Queens. Caruso plays Jimmy Kilmartin, who used to be a drunk and a thief. Now that he and his wife have sobered up and started a family, he wants to stay on the straight and narrow.

But one night his cousin Ronnie comes pounding on the door, desperate, because he has a carrier of stolen cars and if he doesn’t get someone to drive it the mob will kill him. Against his better judgment, Jimmy goes along, and gets caught in a bust that results in the shooting of a cop.

He ends up serving time, but won’t rat on his friends, out of his own highly personal code, which seems glued together out of Mafia honor and his 12-step program. Meanwhile, everybody is betraying him, especially Ronnie, who gets the wife drunk and seduces her, setting up Jimmy’s motive for a dangerous game of double-cross revenge.

There is plot and more plot in “Kiss of Death.” By the time it’s over you may wish you had taken notes, to keep track of who is doing what, and with which, and to whom. A lot of the scheming centers around Little Junior Brown, the Nicholas Cage character. The first time we see Junior, he’s bench-pressing a stripper in his father’s topless bar, called Baby Cakes. This is the kind of “gentleman’s club” where you wonder why any of the customers ever come back again, since if they look sideways at anyone they get pounded by Junior.

A little of Little Junior Brown goes a long way. The part has been overwritten by Price, who gives Junior so many traits that Cage is run ragged keeping up with the weirdness. Junior is a body-builder, and has severe asthma, and adores his father, and can’t stand the taste of metal in his mouth, and compresses his rules for living into “agonyms,” which is how he says “acronyms.” He also likes to debate philosophy, although, in his business, when he asks, “What’s worse? Losing a wife, or a father?” he isn’t dealing in abstractions.

Junior talks like a guy who reads the “Increase Your Word Power” page in the Reader’s Digest; every sentence has one extra word, as in “the difficult becomes the repulsively impossible.” At first he hates Jimmy. Then he gets to like him, and eventually he confides in him: “I never told anybody about me and the metal-tasting before. I hated it in prison. I couldn’t get plastic forks.” One problem with Junior is that the things he says don’t match the things he does; he’s too dumb to be as smart as he is. But Cage is a real movie actor and plays the role with style and bravado.

David Caruso, on the other hand, is a serious problem in the lead.

Sure, he’s the good guy, which is a disadvantage in this movie, but he should project more of a sense of menace.

When he gets into showdowns with tough guys, you don’t see why they should take him seriously. He seems too laid-back and unfocused, and is not able to carry this movie. He doesn’t compel us to identify with him as he winds through the labyrinthine plot.

The conflict in “Kiss of Death” is triangular, involving not only Jimmy against the mob, but also the law vs. the mob, with Jimmy in the middle. He has a lot of trouble with an unforgiving cop (Samuel L. Jackson), and with a district attorney (Stanley Tucci), whose word is meaningless.

Since one of the motifs in the movie is the way Jimmy stands by his word, the message may be that an honest man can’t stand with the cops or the robbers. Jimmy winds up wearing a wire at times and places where common sense indicates it would be discovered, and is saved only by the Bathroom Rule, which indicates toilets in movies are never used for biological purposes, but only to dispose of wires, guns, evidence, etc.

When I’m watching a movie as complex as “Kiss of Death,” I look forward to the ending, since the filmmakers have to somehow tie together all the loose ends. The climax of “Kiss of Death,” set in Baby Cakes, is so ludicrous it could be comedy, with characters arriving, leaving and being killed or saved according to an elaborate plot-driven timetable. Those who remember the original “Kiss of Death” will be waiting for somebody to push a wheelchair down the stairs, but in a plot like this, that would be wretched excess.