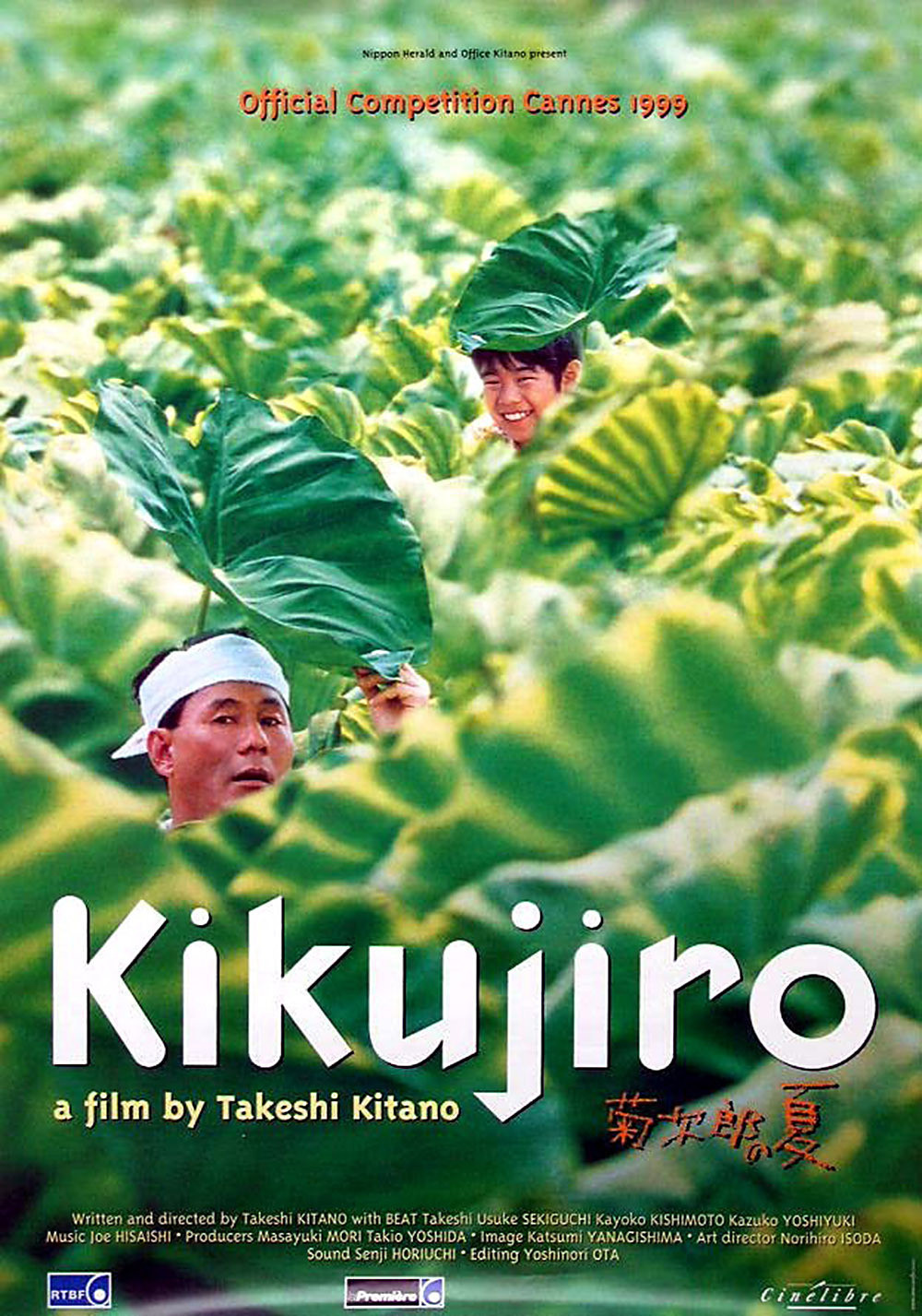

The little boy lives with his grandmother, who leaves food for him before she goes to work. The summer days stretch long, and the streets are empty. He is lonely, and finds the address of his mother, who works far away. He wants to visit her. The grandmother has a friend who has a husband who is a low-level gangster. The gangster is assigned to take the kid to find the mother, and that’s the set-up for “Kikujiro,” which is a lot of things, although one of them is not a sweet comedy about a gangster and a kid.

The movie was made by Takeshi Kitano, Japan’s most successful director, and he stars in it under the name he uses as an actor, Beat Takeshi. Kitano is a specialist in taut, spare crime dramas where periods of quiet and tension are punctuated by sharp bursts of violence. “Kikujiro” is the last sort of film you would expect him to make–even though he skews the material toward his hard-boiled style and away from the obvious opportunities for sentiment.

Kikujiro, known only as “Mister” to the little boy, is played by Kitano as a man who is willing to seem a clown, but keeps his thoughts to himself. His dialogue to the kid is not funny to the kid, but might be funny to a third party, and since there is none (except for the audience), it seems intended for self-amusement. Unlike “Gloria” or “Little Miss Marker,” this movie’s kid doesn’t have much of a personality; he pouts a lot, and looks at Mister as if wondering how long he will have to bear this cross.

The two of them are essentially broke for most of the movie, after Mister trusts the kid’s ability to pick the winners at a bicycle race track. The kid guesses one race right and all the others wrong, and so the man and the boy are reduced to hitching to the remote city where the mother may live. This turns the movie into a road picture that develops slapstick notes, as when Mister tries to stop cars by laying down in the road or positioning nails to cause flat tires. (His efforts produce one puncture, which results in a great sight gag.) Some of the adventures, like the kid’s run-in with a child molester in a park, are fairly harrowing; the movie is only rated PG-13, but we can see why one newspaper mistakenly self-applied an R rating; scenes like this would be impossible in an American comedy, and it’s all Kitano can do to defuse them enough to find comedy (very little, it is true) in them. Other scenes are funnier, including a road relationship with a couple of Hells Angels named “Baldy” and “Fatso,” who despite their fearsome appearance, are harmless. One extended sequence, when the man and boy are stranded at a remote bus stop, has a Chaplinesque quality.

If the movie finally doesn’t work as well as it should, it may be because the material isn’t a good fit for Kitano’s hard-edged underlying style. Japanese audiences would know he is a movie tough guy (Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry is our equivalent), and so they’d get the joke that he seems ineffectual and clueless. Western audiences, looking at the material with less of the context, are likely to find some scenes a little creepy, even though the cheerful music keeps trying to take the edge off. This same movie, remade shot for shot in America, wouldn’t work at all, and only its foreign context blunts the bite of some scenes that are a little cruel or gratuitous.

Still, Takeshi Kitano is a fascinating filmmaker–a man with a distinctive style that’s comfortable with long periods of inactivity. As an action director, he relishes the down time, and keeps the action to a minimum; there is a relaxed rhythm, a willingness to let scenes grow at their own speed instead of being pumped out at top volume. I like the director and his style, but the material finally defeats him. You can’t smile when you keep feeling sorry for the kid–who is not, after all, in on the joke.