Movie publicity is filled with buzzwords about acting, “transformation” in particular, but it’s sad how little practical information we viewers get about that process. It’s often wrapped up in mysticism or ignored entirely; we hear in the abstract that an actor trained as a boxer to play a boxer, or studied someone’s accent in order to play a character of a different nationality or ethnicity, but there are precious few examples of what it actually means to enter another person’s consciousness and become them for purposes of telling a story. “Kate Plays Christine,” about an actress preparing to play a newscaster who committed suicide in 1974, is a rare and welcome exception. But for all of its practical details about what the process of acting is actually about, it’s more than a mere record of things done and said. It blurs the line between fact and fiction, to the point where it seems less of an account of real world events than a fact-fiction blur. The actress repeatedly tells us she is getting ready to play a role in the story of her character’s life but we never see the finished film, because it’s the film that you’re watching. The process of transformation is the story, and the story truly belongs to the artist.

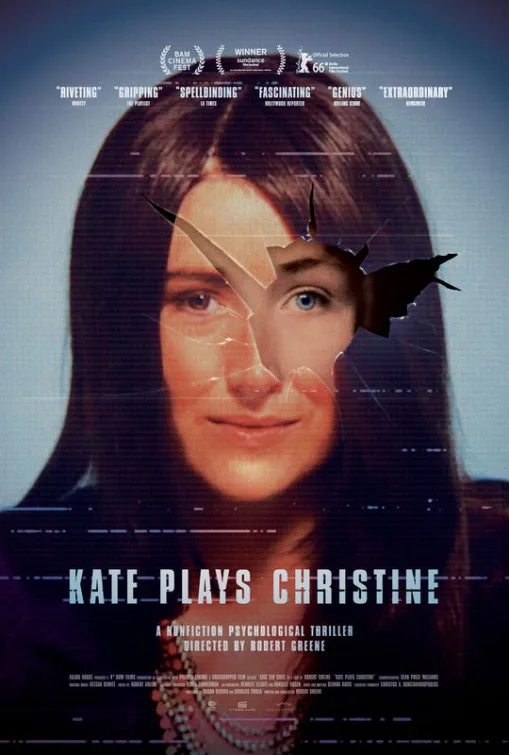

“Kate Plays Christine” is conceived and directed by Robert Greene, a film editor (mainly with director Alex Ross Perry) who is also an accomplished documentary filmmaker; his works all have an aspect of deliberate genre blurring, in particular “Actress,” about a performer putting her career on hold to take care of her family, and “Fake it So Real,” about small-time professional wrestlers in North Carolina. “Kate” focuses on Kate Lyn Sheil (“House of Cards,” “Sun Don’t Shine”), who has been hired to play Christine Chubbuck, a Florida news reporter who is considered to be the first instance in the United States of a person killing herself live on the air: she shot herself in the back of the head during a broadcast and was taken to an emergency room, where she died.

This is a grim assignment, and Sheil treats it with all the gravity it deserves. As she (and we) study the details of Christine Chubbuck’s short life, the movie gives us a sense of the wider context surrounding TV news in the 1970s, and the sexism that affected her professional and personal life. There is something both ghoulish and inspiring about the process of identification depicted here. We learn that Christine had an ovary removed a year before the suicide, and that she was in love with a coworker, a man who read stock market reports on the air, but was rejected by him. We also get a sense of Christine as an isolated and deeply depressed person whose symptoms went largely unrecognized; colleagues who talk about her in the present tense tend to frame her life in terms of the impact that her bloody death had on them, and describe her as simply a serious or “dark” person, rarely giving any indication that she was understood, much less than she had any kind of serious support network.

Kate (it seems wrong to call her by her last name, because the movie is so intimate) begins the process of identification immediately, reading about the case, expressing both relief and dismay that no video exists of the suicide, and trying to study Christine’s vocal mannerisms and posture and get her look right. An early highlight of the process finds Kate sitting with an elderly wigmaker, a widow, who tries to fit her with an approximation of Christine’s long, dark locks. Although Kate doesn’t really look much like Christine in the face—and notice how the wigmaker compliments her on being so much prettier than the dead woman she’s portraying—as she puts on the wig something almost alchemical seems to happen. Greene’s camera frames her alongside an image of Christine, and she seems to be turning into her, like the two women in Ingmar Bergman’s “Persona.”

When actors talk about the adverse emotional effects of playing a dark character for any length of time, there’s a tendency to roll our eyes at them, mainly because of the perception that acting (like filmmaking or writing or music) somehow isn’t “real” work that exacts a different kind of emotional or physical toll. This film puts the lie to that belief. You see Kate becoming Christine, as the title promises, with all the downsides that transformation entails, and it’s not always easy to look at. Much of the time it’s genuinely disturbing. The film sometimes errs on the side of the same kind of mysticism that Kate’s practical approach makes a point of rejecting—there are perhaps too many ominous scenes of the actress being observed from middle distance while a synthesized score drones ominously—but whenever the leading lady is talking to us and to herself, contemplating the work and what it means, the movie is riveting and unique.