I’m not going to bore you with my own handful of personal anecdotes, so you’ll have to take my word for it: The artist Julian Schnabel is the most socially gifted human being I have ever watched work a room, whether that room is a packed party or an intimate conversation space. The now-grizzled, bearish man exudes and controls a charisma that’s hard to quantify.

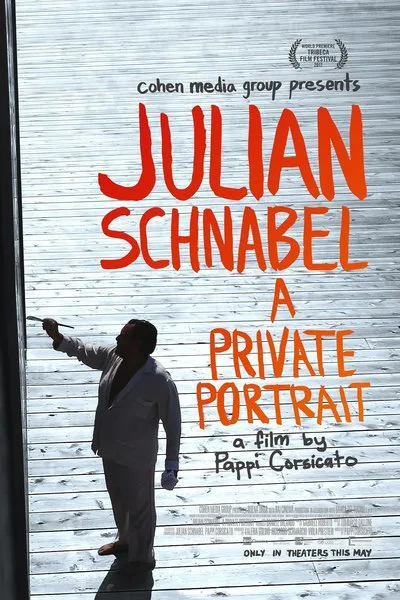

In “Julian Schnabel: A Private Portrait,” Schnabel keeps the personal magnetism burner at low, the better to wax reflective on his life and career in the art-crazy 1980s and beyond. Directed by Pappi Corsicato and executive produced, typically, by the subject himself, the movie is never uninteresting but is often surprisingly low-energy and, even more surprisingly, visually drab.

The movie begins with Schnabel seeming to preside, like a Prospero without the liability of exile, on one of the Li Galli islands on Italy’s Amalfi coast, piggybacking a naked blond infant on his back as he walks to the sea. Stripping off his robe to reveal his once-barrel chest has shifted down to his belly, he nevertheless asserts his vitality with a high dive.

Like Picasso before him, but without, I presume, the sadistic streak, Schnabel is an Imperial Artist, a Caesar by dint of self-proclamation and will, and yes, of talent and an incredible work ethic. In keeping with the movie’s title, the story is told by friends and family. Early childhood in New York; years of acid-dropping, surfing and art-making in Brownsville, Texas; the move to New York, where he worked as a chef in a top restaurant and bounded from the kitchen on occasion to inveigle the favor of dining art dealers; controversial stardom in the 1980s; then on to the occasional but (mostly) very distinguished forays into filmmaking which gained him a whole new cachet. (He won the best director award at the Cannes Film Festival in 2007 for his “The Diving Bell and the Butterfly.”) The interviewees are art world stalwarts such as Mary Boone and Peter Brant, also weighing in are various family members, and by the end of the film one has the impression that Schnabel has fathered something like 40 children, and also given them all jobs on his films.

His personal expansiveness definitely keys into his work. Schnabel is a hard artist to pin down; at one point he’s described as “a figurative artist of great physicality” but that’s not quite enough to categorize him. He became notorious early in his career for “plate paintings,” portraits and figures painted over and around an array of cracked dishware; it’s his signature style but at the same time it’s only one aspect of his work. What it all has in common is being big. I suppose you could call him a maximalist, a gigantist.

I said I wouldn’t share an anecdote, but this one is not lacking in pertinence. In the early 2000s, I was to interview Christopher Walken for Premiere magazine. Walken’s publicist wanted to book a restaurant, and I explained I wanted a quiet place because this wasn’t a “what are you up to lately?” interview but rather an expansive career survey. I believe it was Walken himself who came up with the idea of doing it at his friend Julian’s house/studio, a now-legendary piece of New York real estate in downtown Manhattan atop which Schnabel built a controversial (too high, said the neighbors) Venetian-style addition. (We learn in the film the origin of its name, Palazzo Chuppi.) On arriving, I went to the studio floor, a high-ceilinged loft. In one nook, Schnabel was playing with a new toy, a large-format Polaroid with a baffle that looked like an elephant’s trunk, taking portraits of his pal Chris with it. The rest of the studio was taken up by these large papier-mâché sculptures, three feet high or so on average; and these deliberately crude and almost Play-Doh like figures depicted scenes from Greek mythology. Taking a break from posing, Walken joined me as I looked at a scene of Agamemnon’s bathtub murder. We contemplated it in silence for a bit and Walken said, “Yeah, but where would you put it?” Overall, Schnabel’s work is plentiful and eclectic enough that it’s like the weather in certain locales—if you don’t like one piece of work, wait a while in the virtual slideshow, there’s probably something you’ll take to coming up

It’s too bad Walken isn’t in this film, but Willem Dafoe is, as is much of the cast of “The Diving Bell and the Butterfly,” as are filmmaker friends Hector Babenco and Jean-Claude Carriere. Babenco calls Schnabel “a figure from a Balzac novel,” while Carriere extemporizes on what he feels to be Schnabel’s essential unknowabilty. Schnabel’s friendship and collaboration with Lou Reed is touched upon to moving effect (and Bono turns up for the requisite sound bite in this section). A bit of not-quite-inside-art baseball features critic/historian and Picasso biographer John Richardson, nearly 90 when depicted in the film, seen coming around on Schnabel’s work. The torch is passed, sort of!

Despite its “private portrait” subtitle, there are some corners the film declines to wander into (and here, perhaps, is where the subject’s participation in the production came to bear). There is no mention of 2011’s “Miral,” a Schnabel-directed movie that is not very good at all; nor is his personal involvement with that film’s screenwriter. No mention is made of the fact that the toddler he carries on his back at the movie’s opening has a mother who is wholly other from his second wife Olatz. Not that I’m affronted or feel denied, but these kind of omissions do stand out in this context. My main complaint, as mentioned above, is that for a movie about a visual artist, it’s not very good looking. The original footage looks as if it might have been captured on a color Portapak, and the film clips seem to have gotten slathered with video noise in the transfer. Back in the day, Schnabel might have arranged for his self-tribute to screen in Glorious Technicolor, Breathtaking CinemaScope, etcetera. Wonder what happened.