Norman Jewison’s “Jesus Christ Superstar” is a bright and sometimes breathtaking retelling of the rock opera of the same name. It is, indeed, a triumph over that work; using most of the same words and music, it succeeds in being light instead of turgid, outward-looking instead of narcissistic. Jewison, a director of large talent, has taken a piece of commercial shlock and turned it into a Biblical movie with dignity.

That isn’t easy to do. The life of Christ would seem to have an innate dignity to it, but only in such rare films as Pier Paolo Pasolini’s “The Gospel According to St. Matthew” or Martin Scorsese’s “The Last Temptation of Christ” has Christ come off as human, strong and reachable. The character has a tendency to disintegrate before our eyes; it’s the only male role we can imagine where the cinematographer considers gauze over the lens. Christ seems wispy and too ethereal, and Mary Magdalene begins to steal scenes. The lowest point in this sort of thing was reached by Jeffrey Hunter as Christ in the remake of “King of Kings”–but let that memory steal quietly away.

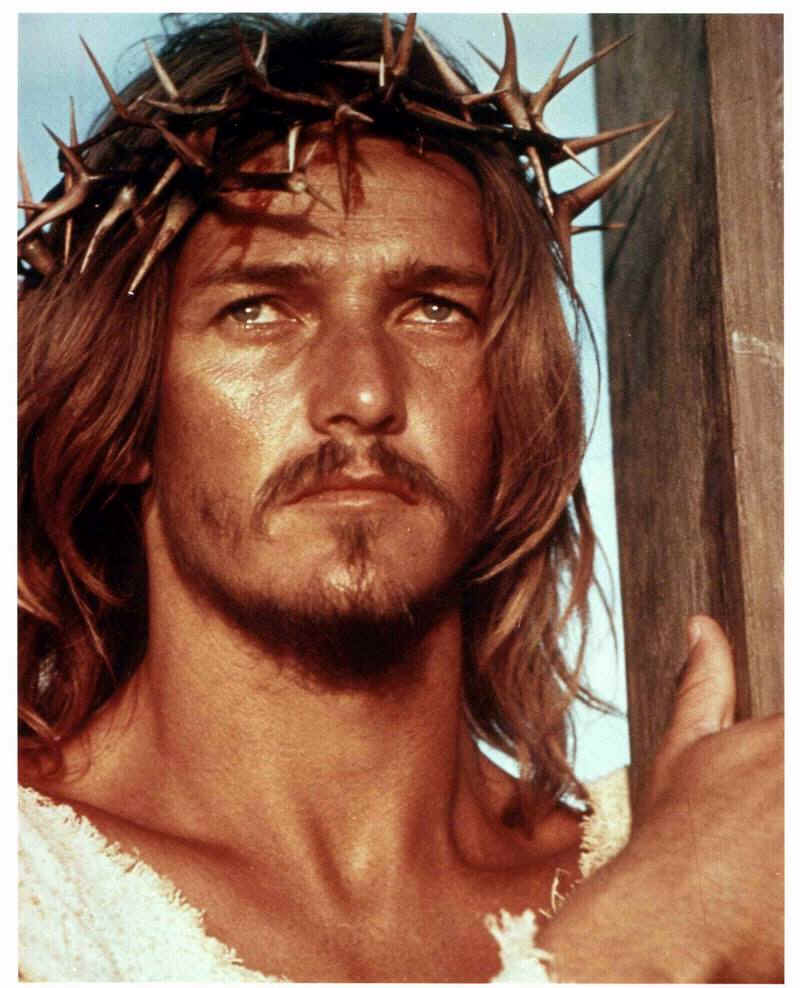

Norman Jewison gives us a likable Christ in Ted Neeley, who sometimes seems a little bemused by his superstar status. The premise of the movie is that Christ was the first superstar–the first man with a hyperthyroid charisma. The ordinary people around him begin to get a little worried after a while; they like him and don’t want him to get in trouble with the Romans. Most worried of all is Judas, who advises Christ to maintain a low profile.

He doesn’t of course; but in deference to the several readers who didn’t like my review of “The Last of Sheila” because I gave away too much of the plot, I won’t reveal what happens to Christ in the end. Along the way, though, Jewison and his cinematographer Douglas Slocombe give us some of the most spectacular wide screen photography since “Doctor Zhivago,” and they achieve a color range that glows with life and somehow doesn’t make the desert look barren.

Individual moments have such beauty and grace that you’re afraid to think of the pains that must have been necessary to get them. There are extreme long shots of characters isolated in a vast wilderness; there are lonely shots into the sun of ancient monuments; and there’s one absolutely stunning shot that shows us an apparently empty landscape and then tilts down to reveal Jesus and his disciples in a gigantic, sunlit cavern.

The movie has become controversial for a couple of reasons: Jewish groups have attacked it for being anti-Semitic, and some reviewers have wondered aloud why the only black in the movie happened to be cast as Judas. Jewison is wrong, of course, to blame the death of Jesus on the Jews; the Roman Catholic Church, which hasn’t exactly been in the vanguard on this question, officially decided some years ago that the doctrine of collective Jewish responsibility was in error. That’s in line with the historical scholarship on the subject. But Jewison is dealing with a fantasy about the life of Christ, not fact, and if he wants to typecast, that’s his right as a filmmaker. We also have the right to be offended.

As for the black Judas, I really don’t think there’s any reason to be concerned after seeing Carl Anderson’s fine performance in the role. He has an energy and strength that makes Judas seem recognizably human, for a change, instead of that vapid little sneak over on the right-hand side of the canvas with the bag in his hand. Jewison suggests that Judas (by his own lights, anyway) had a legitimate concern about Christ’s popularity. And in the Jewison version, Judas doesn’t so much as betray Christ for the pieces of silver as make a tactical error in his dealings with the Romans. Interesting.

The music is clear and bouncy, and the movie sound track album should be a better version of the rock opera than the original. Jewison is especially good with peppy numbers like “What’s the Buzz?” and we never get the feeling he’s manipulating his characters or forcing them into staged-looking choreography. They inhabit the desert freely, enacting their story as if it were not the central event in the Christian religion but rather the interesting career of a promising young man.