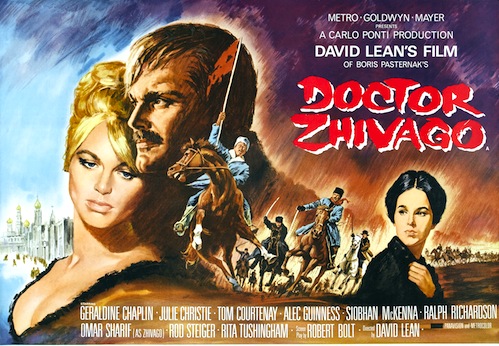

When David Lean’s “Doctor Zhivago” was released in 1965, it was pounced upon by the critics, who found it a picture-postcard view of revolution, a love story balanced uneasily atop a painstaking reconstruction of Russia. Lean was known for his elaborate sets, his infinite patience with nature and climates, and his meticulous art direction, but for Pauline Kael, his “method is basically primitive, admired by the same sort of people who are delighted when a stage set has running water or a painted horse looks real enough to ride.” Sometimes one must admit one is precisely that sort of person. I agree that the plot of “Doctor Zhivago” lumbers noisily from nowhere to nowhere. That the characters undergo inexplicable changes of heart and personality. That it is not easy to care much about Zhivago himself, in Omar Sharif‘s soulful but bewildered performance. That the life of the movie is in its corners (the wickedness of Rod Steiger‘s voluptuary, the solemn pomposity of Tom Courtenay’s revolutionary). That “Lara’s Theme,” by Maurice Jarre, goes on the same shelf as “Waltzing Matilda” as tunes that threaten to drive me mad.

And yet the stage has running water, and the horses look real enough to ride. “Doctor Zhivago,” restored and revived for its 30th anniversary, is an example of superb old-style craftsmanship at the service of a soppy romantic vision, and although its portentous historical drama evaporates once you return to the fresh air, watching it can be seductive. Consider, for example, the early shot of the red star glowing above the dark tunnel opening where the workers march in and out. The shot of a child peering through a frosted pane with the claws of branches tapping against it. The cavalry charge on the Bolshevik marchers. Or the way snow crystals dissolve into flowers, and a flower dissolves into Lara’s face.

Lean did nothing less than recreate Moscow and its countryside at the time of the Russian revolution, using locations in Spain and Canada (which supplied the vast landscape with the tiny train making its way across it). He accepted the challenge of setting most of the key scenes in winter, with all the attendant difficulties of photographing snow (both artificial and real). There is a moment when Zhivago and Lara enter the abandoned dacha, and the snow and frost have preceded them, turning everything into a winter fairyland. It is a scene where you simultaneously think about the skilled set decoration, and catch your breath at the beauty.

The story is based on Boris Pasternak’s novel, much praised on its publication in 1958 as a daring defiance of Russian censorship.

So it was, but today the story, especially as it has been simplified by Lean and his screenwriter, Robert Bolt, seems political in the same sense “Gone With the Wind” is political, as spectacle and backdrop, without ideology.

The specific political content of “Doctor Zhivago” is seen mostly as sideshow: Charges by the Czar’s troops on demonstrating students; the caution of Alec Guinness’ Soviet official; the unyielding way in which Tom Courtenay’s general, once a poet, now says “history has no room for personal feelings.” “Doctor Zhivago” believes that history should have a lot of room for personal feelings – that the problems of its little people do amount to more than a hill of beans – and that’s perhaps why the Russian’s didn’t like Pasternak: He argued for the individual over the state, the heart over the mind.

The first two hours of the 200-minute movie are the best, and the most personal. Rod Steiger gives one of the performances of his career as Victor Komarovsky, the investor and scoundrel who victimizes first a woman and then her daughter, Lara (Julie Christie). Zhivago (Omar Sharif) first meets Lara at this time; he attends at the mother’s deathbed, and later looks on as she enters a wedding party and shoots at Komarovsky, gaining a vision that he will carry with him through his marriage to the loyal and steadfast Tonya (Geraldine Chaplin).

Zhivago is cold to Komarovsky: “What happens to a girl like that when a man like you is finished with her?” The response is colder: “Interested? I give her to you – as a wedding present.” This sets up Zhivago’s romantic obsession, which finds its moral justification when the doctor meets Lara, now a nurse, behaving heroically on a battlefield. There is the temptation to get so swept up in their idealism that we forget (come on!) that the old doctor-and-nurse routine is a venerable building block of soap opera.

Watching the film again, I found it hard to believe that the Chaplin character could be so understanding. Later, when Komarovsky offers Lara an opportunity to save the life of herself and her child, call me a realist, but I thought she should have taken it. And the final pathetic scene, with Zhivago staggering after the woman on the Moscow street, is unforgivable. So, yes, it’s soppy and manipulative and mushy. But that train looks real enough to ride.