Men in the films of Patrice Leconte sometimes find themselves in a kind of paralysis of admiration for women. Consider the hero of “The Hairdresser's Husband,” who as a child developed an erotic obsession involving female hairdressers and their rituals and powders, their scents and tools, and now operates a beauty shop simply so that he can gaze in admiration as his wife cuts hair. Or consider “Monsieur Hire,” about a mousy little man who becomes aware that he can see into a seductive woman’s bedroom across the air shaft from his flat. When she makes it clear she knows he is watching her and doesn’t mind, his distance from her is threatened and he is profoundly shaken.

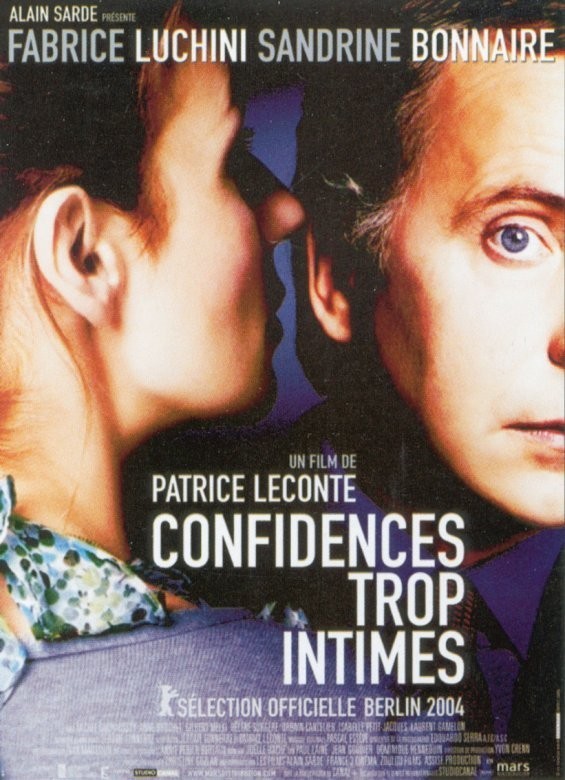

Now here is William Faber (Fabrice Luchini), a quiet, precise middle-aged man who still lives in the flat where he was raised, and carries on the accounting business his father established there. He hasn’t gone far from home. Even his father’s secretary, Madame Mulon, still works for him. He is a man for whom probity is a cardinal virtue, and revealing passion is unthinkable.

One day a nervous young woman named Anna Delambre (Sandrine Bonnaire) walks into his office, lights a cigarette, and begins to spill the beans. She is so nervous that the camera becomes uneasy, regarding her with jerky little noticing shots. She talks frankly of problems in her marriage. William remains almost motionless behind his desk, his face a study in astonishment and alarm. The few words that he speaks are noncommittal and open-ended.

She thinks he is a psychiatrist. He is not, but doesn’t tell her that, and as she continues her visits he ignores the withering stares of Madame Mulon and sits sphinx-like behind his desk, hardly moving a muscle, listening to her story as it grows steadily more strange and, it must be said, more erotic — so much so you would almost think Anna was trying to arouse the him.

You may think I have revealed a great secret by explaining the mistaken identity. If Leconte were a lesser filmmaker, that would be true. But Leconte and his writer, Jerome Tonnerre, present her error and his deception only to prepare their canvas. We find we cannot take anything for face value in this story, that the motives of this woman and her husband are so deeply masked that even at the end of the film we are still uncertain about exactly what to believe, and why.

What is real is William’s fascination. He doesn’t move a muscle, say an unnecessary word, reveal in any way how transfixed he is by Anna and her story. But certainly she knows. There’s something deeply sexual in a woman’s discovery that she has ultimate power over a man, and one possibility is that she continues her visits to the wrong office because they excite her. There is also the possibility that her original motive changes in response to new developments. There is the mystery of her relationship with her husband, who she seems to have accidentally crippled with the car, so that he walks with a cane. And the matter of what her husband wants her to do. And the way in which this is made known to William.

Bubbling away beneath most of Leconte’s films is a stream of wicked humor. He is incapable of a film that exists on one level, for one purpose. He is quite capable, as in “Intimate Strangers,” of telling a story that has completely different meanings for the major characters, so that although they occupy the same rooms and hear the same words, they don’t perceive the same scenario. And then with what delight he surprises us — not with anything so vulgar as a twist, but with a revelation of character so sudden it’s like a psychic blow.

His camera is a co-conspirator in “Intimate Strangers.” We are invited to become voyeurs as we follow the progress of the perverse therapy sessions — sessions which may be doing Anna as much good as if William really were a psychiatrist, although what would be good for Anna becomes increasingly hard to say. William watches this woman as she does small but closely observed things, like tipping the ash of her cigarette into a wastepaper basket. No, that doesn’t start a fire — not in a Leconte film — but functions simply to make her seem reckless.

Consider a high-angle shot late in the film, which establishes that Anna is wearing a dress displaying noticeable cleavage. Now watch as Leconte cuts to William, whose gaze begins to waver as he tries resolutely not to look, and then notice the reaction shot (now our point of view as well as William’s), as the camera hovers almost unsteadily, begins to dip to regard her neckline, and then subtly refuses to. William has not looked, but Leconte has demonstrated that we wanted him to. No big point is made of this, but some members of the audience actually crane their necks, trying to get a better angle through the camera lens.

Leconte is not famous, but he is addictive. You could do worse than hole up for a weekend with half a dozen of his films, also including “Ridicule,” “The Girl on the Bridge,” “The Widow of Saint-Pierre” and “The Man on the Train.” His characters are fascinated by other lives, and by missed opportunities in their own. They think they know their motives, and then life reveals their real motives to them. They are presented with feelings that may be shameful, but are undeniable, and are theirs. It is up to them to decide if they would become more miserable through the realization of their desires or through the tantalizing denial of them.