Children play on a playground in Jackson Heights, Queens, running through sprinklers, batting at oversized chimes. Parents and sitters look on. On another street in the neighborhood, people march to protest a local restaurant that denied service to a transgender woman. In a mosque, men pray and listen to a sermon. Soccer fans gather outside an electronics store with a huge flatscreen TV in the front window, watching the game; their anxious faces are reflected in the glass. At a farmer’s market, stall-keepers lay out their wares and residents inspect them: tomatoes, zucchini, strawberries, cherries. In a halal restaurant, a man butchers and plucks chickens and ducks. In a city councilman’s office, a woman listens patiently on the phone to a constituent who has a problem and tries to let her know as politely as possible that she’s not agreeing or disagreeing with her, she’s just listening. The sun rises on Jackson Heights. The sun sets. The sun rises and sets again. The city noise creates its own abstract collage of music and sound: salsa, marimba, jazz, soul, sirens, cell phone rings, alarms, the hiss of city buses braking and the whine of their acceleration, the rumble and rattle of elevated trains.

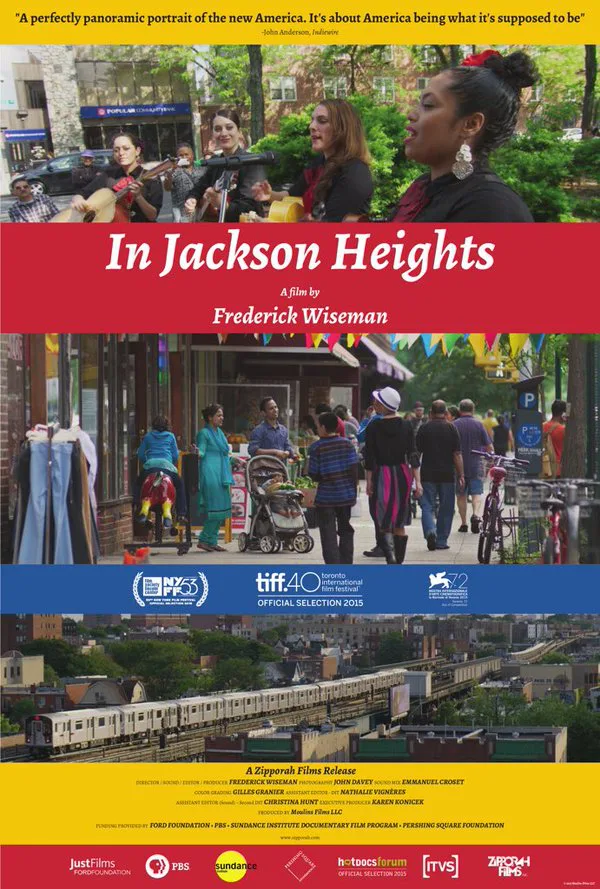

Too lyrical? Too abstract? Too bad. The film is the film. The film is “In Jackson Heights.” It’s hard to write about “In Jackson Heights” without sounding like you’re trying to write poetry.

That’s how precise Frederick Wiseman’s new documentary is. That’s how refined the 85-year old director’s aesthetic has become.

As in nearly all of his previous movies—stretching back fifty years, astoundingly—Wiseman practices what journalists would call “pure reporting.” Which means there’s no hook, no obvious narrative spine—he’s just decided to go somewhere and hang out and watch people and listen to them and then report on what he saw and heard. This movie is the report. It’s a reporter’s notebook of a movie. And it might be the lightest, loosest warmest nonfiction film he’s made since “Boxing Gym,” and maybe ever.

Wiseman makes movies about institutions of one sort or another: high schools, army bases, domestic violence shelters, New England towns, college campuses. They are not about what’s right or wrong with the institutions, although if you watch them closely you might get a clue about the filmmaker’s opinion; the way he arranges material suggests one possible way of thinking about the subject, or one possible conclusion to draw, without ever closing down alternate avenues of interpretation. The films are by necessity decentralized, but they are not disorganized. There’s an internal logic to how they’re put together. A Wiseman logic. Wise man’s logic.

David Simon, the creator of “The Wire” and “Treme,” is on record saying how much he admires Wiseman, and you can see in Simon’s work certain affinities, particularly his conviction that stories about communities be told as democratically as possible, jumping among lots of characters and trying to give them something like equal weight, no matter what they happen to be going through. The films of Robert Altman (“Nashville,” “Short Cuts“) and Richard Linklater (“Dazed and Confused,” “Bernie“) often practice something like a Wiseman aesthetic, too. There are certain methods for telling this kind of story, intuitive ways. Wiseman is the master.

Watch “In Jackson Heights” and notice how he gets from one location to another. His cameras might be spirits that can disappear and reappear in increments. We’re in a place, we stay there a while, we listen to neighborhood advocates talk about a rental crisis or an immigrant’s rights group sharing stories about the perils of getting relatives from Mexico to the United States. And then we leave. We leave by moving outside of the building and standing on the street. Then we move to another street. Maybe we look at a street sign or the exterior of another storefront, or a restaurant under a stretch of elevated train track, or the front door of a house on a leafy residential street. And then we’re inside meeting new people, hearing new stories, experiencing different lives.

But they’re all the same life, in a way, because they are all alive at this moment (the film was shot in the summer of 2014 and ends with Fourth of July fireworks) and because they are all Americans, or people living in the United States, or because they are simply people, and simply living, and often living simply. Wiseman has occasionally been rapped as a cold or even misanthropic director; I’ve never seen that in his films, but that’s one rap against him.

In any case, “In Jackson Heights” is the most vibrant refutation of the charge that I’ve seen, and I’ve seen a lot of Wiseman films. Every frame of it seems delighted by people, delighted by cities, by neighborhoods, delighted by life itself. It’s warm and attentive. It cares about every person, every story, that passes before the camera’s lens, and about the hints of stories contained in fleeting closeups of old women listening to street musicians and old men sitting on park benches and city workers counseling voters and restaurant workers getting through the day. There is a subtle gratitude to the way Wiseman and his sound editors weave city noises (the Mr. Softee ice cream jingle, for example) throughout the film, linking one location to another, one life to another, as if to affirm that it doesn’t matter if you’re black, white, brown, Irish, Italian, Mexican, Dominican, Jewish, Muslim, male, female, straight, gay, bisexual, transgender, adult, juvenile, anyone, anything, it’s all the same life, the only difference is what corner of it we inhabit, what piece of it we see.

Despite its talk of citizenship and what it means to be a New Yorker and a U.S. citizen, “In Jackson Heights” is less patriotic than humanistic. It’s glad to be alive and glad that other people are, too.

“I was happy till my husband died,” says a very old woman in a nursing home. “There’s nobody left in my family, nobody, and if there is, I don’t know of them.”

Another old woman notes how very old she is, then asks her, “What’s your secret?”

“If I find out what it is,” she replies, “I’ll tell you.”