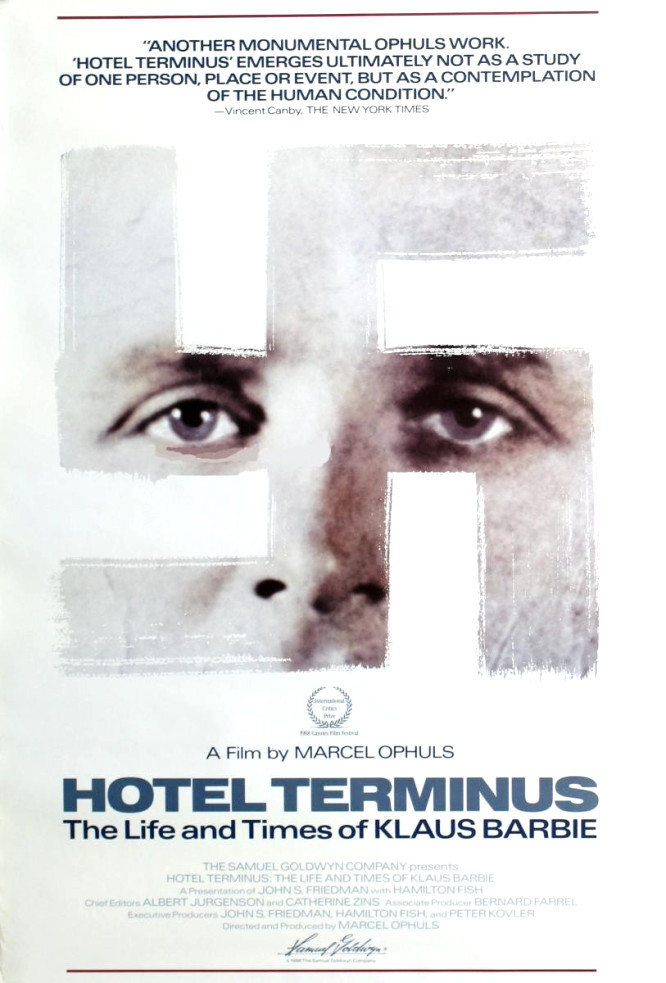

Over and over, during the course of the film, people protest that Ophuls is asking questions about things that happened “over 40 years ago.” If that were true, it would not be a reason to avoid asking the questions. But it is not true. The whole point of the movie is that Barbie’s war did not end with everyone else’s, with the defeat of Nazi Germany.

Barbie was one of the lucky ones whose skills (mostly torture and interrogation) were useful to the postwar Allies in their fight against communism. So he was sheltered from charges of war crimes, used by various agencies (most notably the CIA), and eventually provided with a new identity and resettled in South America – where he continued to practice his torturer’s trade.

Barbie was eventually located and denounced by anti-Nazi groups, was extradited by Bolivia, stood trial in Germany, was convicted of war crimes including the sentencing of 41 orphans to Nazi war camps, and is serving a life sentence. “Hotel Terminus” is not about his capture, trial and conviction. It is about how people remember him.

Some remember what they want to remember, others remember what they cannot forget. In the film’s most harrowing monologue, a woman describes how Barbie methodically tortured one particular prisoner – her father. In other interviews, we learn that Barbie “made the Gestapo respectable” in Lyons by joining it, that he may have betrayed various Resistance fighters, that he enjoyed hitting people, and also that he was a “nice” man, an intelligent man, and a man who was useful to the Allies after the war. As we listen to retired American intelligence agents describe how they used him, there is the impression that he was just the man they needed, a man not too squeamish to do the dirty jobs they were reluctant to do themselves.

Ophuls is a man with a highly developed sense of irony, and in editing more than 120 hours of interviews into a 267-minute film he has often selected moments that are rich with self-contradiction. One man, for example, observes that his dog liked Barbie, “and you can’t fool a dog.” Of course you can fool a dog – and its owner. Other interview subjects are almost absurd as they do verbal handstands to avoid admitting what they almost certainly knew, did and said.

I felt outrage as I viewed these scenes, and I noticed a curious thing within myself: At times I was more outraged at the “good citizens” – the retired American spies, the postwar officials – than I was at Barbie. That was because I accepted that Barbie was evil but I did not want to accept that our side would leap to shelter him and work for him. It is easier when all of the Nazis are Germans, but harder when we cannot isolate the evil of Nazism in the historical past, and have to accept that several U.S. administrations and even the Vatican were willing to protect this man.

The other sensation I felt was the hypnotic rhythm of Ophuls’ reporting process. Long films create a time of their own. Films like “Shoah,” “Little Dorrit” and “Hotel Terminus” cut us loose from the expectation of a beginning, middle and end, and leave us adrift for long periods in the center of the film with no shore in sight. Without a story structure to guide us, we become the accomplices of the director – his passengers. We go where he goes. Ophuls asks the same questions again and again, until we grow as angry as he does by the evasions of the answers. When he grows sarcastic (ridiculing one man who will not talk to him by interviewing the cabbages in his garden), it is a relief – we’re fed up, too. By the end of “Hotel Terminus,” we have become absorbed somewhat into the filmmaking process; in a strange way, we have gone on the same quest as Ophuls.

“Hotel Terminus” is not a great film, like Ophuls’ “The Sorrow and the Pity,” his masterful indictment of the French who collaborated with the Nazis. It is almost deliberately a film in a minor key, a stubborn film, a gadfly’s film, the film of a man who agrees with you that the Nazis were monsters, but adds that he hopes you won’t mind if he clears up a few other details, such as the utter embarrassment of the postwar history of Barbie. “The Sorrow and the Pity” was the film of a man who held his audience spellbound. “Hotel Terminus” is the film of a man who continues the conversation after others would like to move on to more polite subjects. It is a stubborn, angry, nagging, sarcastic assault on good manners, and I am happy Ophuls was ill-tempered enough to make it.