After a summer filled with retreads, ripoffs and whatever in God’s name that thing with Kevin Spacey as the talking cat was supposed to be, most moviegoers are at the point where they are desperate for something that doesn’t look like it will actively insult their intelligence. At first glance, “Hell or High Water” would seem to be just the candidate—it is written by Taylor Sheridan, whose first produced screenplay became last year’s largely acclaimed thriller “Sicario,” and directed by David Mackenzie, the British filmmaker behind such intriguing works as “Young Adam,” “Perfect Sense” and “Starred Up.” “Hell or High Water” even features a cast led by the national treasure that is Jeff Bridges. And yet, while moviegoers desperate to see anything that doesn’t involve a superhero may be willing to overlook its shortcomings, others will undoubtedly be disappointed to find that it’s somewhat less than the sum of its parts.

As the film opens, brothers Toby (Chris Pine) and Tanner (Ben Foster) arrive at a remote Texas Midland bank branch to rob it. While there are some hiccups, they make off with the loose bills in the registers. They then proceed to do the same thing at another branch of the same bank, and while things go a little smoother, the end result is the same. As crime sprees go, these jobs aren’t that impressive on the surface, but, as we soon discover, there is a lot more going on with them than meets the eye. Texas Midland is the bank, we soon learn, that has recently foreclosed on the family ranch after some shady but legal maneuverings. To prevent losing the place and all it represents (which is much more than initially meets the eye), the quietly intelligent Toby has hit upon an ingenious plan to rob a string of Texas Midland branches—only taking the register money to avoid dye packs and the interest of anyone other than local cops—and then using their own money to pay back the debt. He has even figured out a particularly clever way of laundering the take. If not for the occasional danger represented by the more hotheaded Tanner, it would seem like the perfect crime spree—no one gets hurt too much and the victim, frankly, has it coming.

While most of the police investigating the robberies indeed fail to give them much notice, U.S. Marshall Marcus Hamilton (Jeff Bridges), an avuncular lawman on the verge of retirement who comes across like a combination of Columbo and Deputy Dawg, isn’t so sure. What looks like sloppiness to his colleagues—not even trying to go for the big money—seems to him like exceedingly clever planning. As Hamilton and his half-Comanche partner Alberto (Gil Birmingham) pursue their unknown quarry, they even develop a certain degree of admiration for the robbers because of the discipline driving their robberies. That said, this is still criminal activity, and when Tanner impulsively decides to pull a heist on his own that lacks the careful planning of the other jobs, it yields just enough information for Hamilton to start figuring things out. It also requires an acceleration in Toby’s planning, which ends up throwing things out of balance in ways surprising and potentially tragic for all involved.

The early scenes of “Hell or High Water” are the best. After seeing so many meticulously choreographed bank heists that try their damnedest to outdo the likes of “Heat,” it is amusing to see one staged on a smaller and more realistic scale. It becomes even more interesting once we understand that there is more going on than immediately meets the eye. However, once writer Taylor Sheridan has established the basic premise, he doesn’t seem to have much of an idea of how to fill the hour or so between those early scenes and the climactic moments. Instead, he appears to have elected to raid the Cormac McCarthy playbook in order to employ the celebrated author’s sparse and laconic tone wherever possible. Sometimes this works, as in the punchy and pungent lines of dialogue that crop up from time to time (Hamilton has a great one when he spies a bank manager he wants to talk to and remarks, “Now that looks like a man who could foreclose on a house”) or in some bits of bloody black humor, such as the moment when the brothers try to take a bank where the customers are packing more heat than the guards. More often than not, however, it tries so hard to emulate the likes of “No Country for Old Men” at times that you can feel it practically straining from the effort without quite pulling it off. The finale is a particular disappointment—it is staged and performed about as well as can be but the whole scene is just so unlikely that it fails to have the impact that Sheridan and Mackenzie clearly desired.

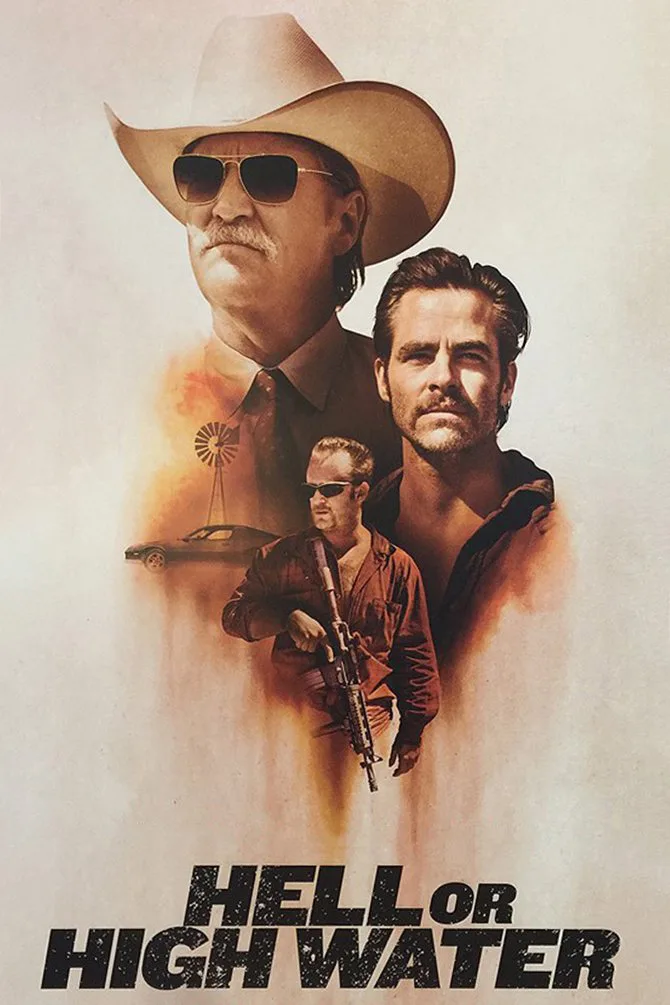

Even though none of them are especially revelatory, the performances are probably the best thing to be had in the film. The most surprisingly satisfying of the bunch comes from Chris Pine, who turns in his best work to date in a part that finds him dialing down the smirky charm of his nouveau Captain Kirk in order to play a far more serious-minded character. As his brother, Ben Foster is okay but at this point in his career, he might do well to avoid playing any characters in the near-future that could be described as “twitchy.” As for Jeff Bridges, he is entertaining to watch—of course, one could count the number of his non-entertaining performances on one hand and still have room left over in case “The Giver 2” ever becomes a thing—but this is not a performance that will linger heavily in future Lifetime Achievement Award highlight reels. Of the various supporting turns, the spikiest one comes from Katy Mixon as a bone-tired waitress who receives a large tip from a guilt-ridden Toby and lets Hamilton have it—not the money—when he requests that she turn it over as being potential evidence.

It’s frustrating that “Hell or High Water” contains so many good things that just don’t coalesce into a fully satisfying moviegoing experience. The story as a whole is a little too derivative for its own good and not even the strong elements are quite able to compensate for that. Of course, seeing as how even vaguely competent films have been so few and far between as of late, some viewers may be a little more willing to overlook its flaws—to wildly paraphrase one of the key lines from “No Country for Old Men,” “If it ain’t a good movie, it’ll do till the good movie gets here.” If only it had spent a little more time trying to find its own voice and a little less overtly trying to ape the styles of its influences, “Hell or High Water” might have been as good of a movie as it wishes it was.