“I enjoy playing the audience like a piano.” — Alfred Hitchcock

So does John Carpenter. “Halloween” is an absolutely merciless thriller, a movie so violent and scary that, yes, I would compare it to “Psycho” (1960). It’s a terrifying and creepy film about what one of the characters calls Evil Personified. Right. And that leads us to the one small piece of plot I’m going to describe. There’s this six-year-old kid who commits a murder right at the beginning of the movie, and is sent away, and is described by his psychiatrist as someone he spent eight years trying to help, and then the next seven years trying to keep locked up. But the guy escapes. And he returns on Halloween to the same town and the same street where he committed his first murder. And while the local babysitters telephone their boyfriends and watch “The Thing” on television, he goes back into action.

Period: That’s all I’m going to describe, because “Halloween” is a visceral experience — we aren’t seeing the movie, we’re having it happen to us. It’s frightening. Maybe you don’t like movies that are really scary: Then don’t see this one. Seeing it, I was reminded of the favorable review I gave a few years ago to “Last House on the Left,” another really terrifying thriller. Readers wrote to ask how I could possibly support such a movie. But it wasn’t that I was supporting it so much as that I was describing it: You don’t want to be scared? Don’t see it. Credit must be paid to filmmakers who make the effort to really frighten us, to make a good thriller when quite possibly a bad one might have made as much money. Hitchcock is acknowledged as a master of suspense; it’s hypocrisy to disapprove of other directors in the same genre who want to scare us too.

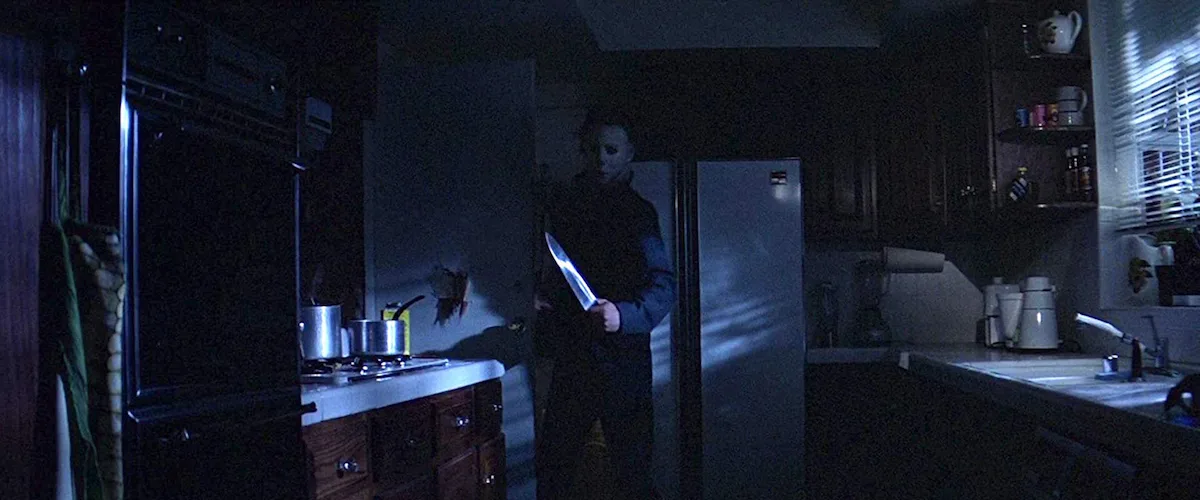

It’s easy to create violence on the screen, but it’s hard to do it well. Carpenter is uncannily skilled, for example, at the use of foregrounds in his compositions, and everyone who likes thrillers knows that foregrounds are crucial: The camera establishes the situation, and then it pans to one side, and something unexpectedly looms up in the foreground. Usually it’s a tree or a door or a bush. Not always. And it’s interesting how he paints his victims. They’re all ordinary, everyday people — nobody’s supposed to be the star and have a big scene and win an Academy Award. The performances are all the more absorbing because of that; the movie’s a slice of life that is carefully painted (in drab daylights and impenetrable nighttimes) before its human monster enters the scene.

We see movies for a lot of reasons. Sometimes we want to be amused. Sometimes we want to escape. Sometimes we want to laugh, or cry, or see sunsets. And sometimes we want to be scared. I’d like to be clear about this. If you don’t want to have a really terrifying experience, don’t see “Halloween.”