“Maybe it is like a mirror,” Makavejev told me late one night in Chicago. “People hold it up to themselves and see reflected only what they are most offended by.” That has a way of happening with his work. “Sweet Movie” (1974) was described by Time as “not a movie — a social sickness.” At that crucial period in history spanning the late 1960s to the late 1970s, Makavejev (born 1932) was the most eclectic, eccentric, impenetrable, jolly anarchist to come out of eastern Europe.

He was from Yugoslavia, that late country, and ethnically Serbian, but international to the core. The director of the first Serbian talkie has a line in Makavejev’s “Innocence Unprotected” (1967) that could apply to Makavejev himself: “Gentlemen, I assure you the entire Yugoslavian cinema came out of my navel. In fact, I have made certain inquiries, and I am in a position to state positively that the entire Bulgarian cinema came out of my navel as well.” The movie, a comic treasure, contains most of the footage of the 1944 talkie, about an acrobat whose daring stunts were recycled as patriotic resistance to the Nazis. Makavejev revisits the director, the acrobat, and others who were involved.

That night in Chicago we were walking up Lincoln avenue to see the Biograph theater, where Dillinger was shot by the FBI. Makavejev was in the city for a retrospective of his work at Facets Multimedia, and eventually he and several Facets workers ended up in my kitchen, eating vegetable soup and solving the problems of the cinema.

In a real way, Makavejev is his films. Like Andrei Tarkovsky, Guy Maddin, Russ Meyer or Alejandro Jodorowsky, he cannot help but make the films he makes, and no others. In his early career in Yugoslavia, in movies like “Love Affair, or the Case of the Missing Switchboard Operator” (1967), he delighted in sneaking political parallels past the censors; he was not anti-communist but anti-authority. The man in charge of film funding in Yugoslavia was an old classmate of Makavejev’s. Faced with one of his scripts, the man sighed: “Dusan, Dusan, Dusan! I know what you are really saying in this screenplay, and you know what you are really saying. Now go home and revise it so only the audience knows.”

Bald, burly and bearded, Makavejev has fashioned a career out of poverty, windfalls, luck and genius. The year “Sweet Movie” played at Cannes, he had a suite at the Carlton Hotel. The next year, I asked him if he was staying at the Carlton again. “Wife and I have tent on beach,” he said. “Some years Carlton, some years beach.”

The plots of his earlier movies are almost impossible to describe, although such later titles as “Montenegro” (1981) and “The Coca-Cola Kid” (1985) are more linear. “Montenegro,” a brilliant seriocomedy, is about a bored American wife in Stockholm (Susan Anspach) who escapes her marriage and spends two wild, liberating nights in a nightclub frequented by Serbo-Croatian immigrants. “The Coca-Cola Kid” stars Eric Roberts as a man from headquarters in Atlanta who is dispatched to Australia to find out why one district drinks absolutely no Coke.

The critic Jonathan Rosenbaum speaks of Makavejev’s method as materials in collision; he combines documentary, fiction, found footage, direct narration and patriotic music in ways startling and puzzling. The movie is about whatever impression you leave it with.

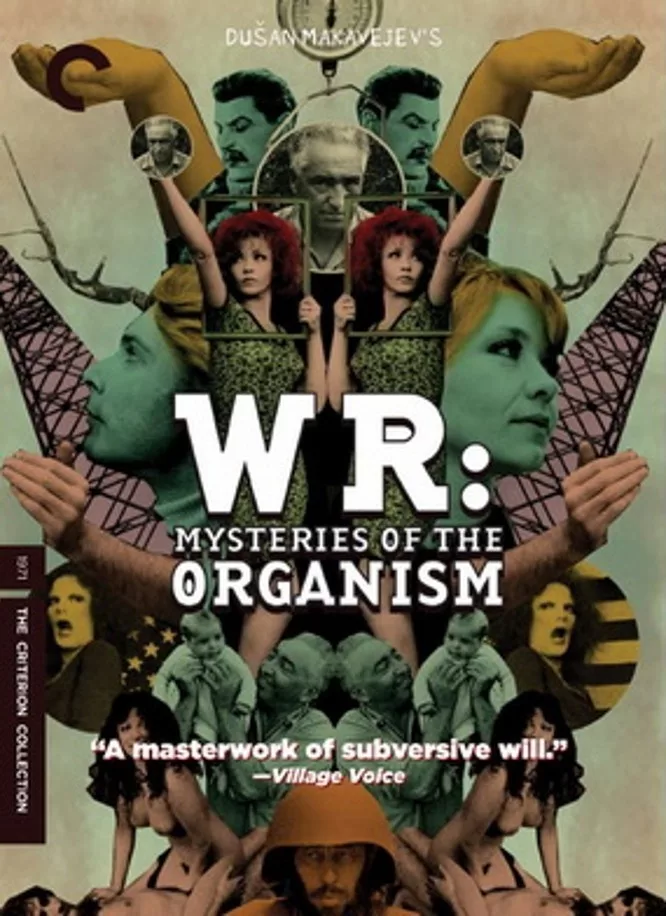

“WR,” for example, begins as a documentary about the Austrian analyst Wilhelm Reich, once Freud’s first assistant, later a communist, later an anti-communist, eventually an American, who believed the orgasm was the key to freedom and happiness, and possibly a cure for disease. His Orgone Accumulator was a box the size of a phone booth, wood on the outside, lined with metal, which he believed concentrated orgasmic energy within anyone sitting inside of it. Reich’s science was condemned by the FDA, his books were burned by the U.S. government, and he died in prison. You see how dangerous sex is.

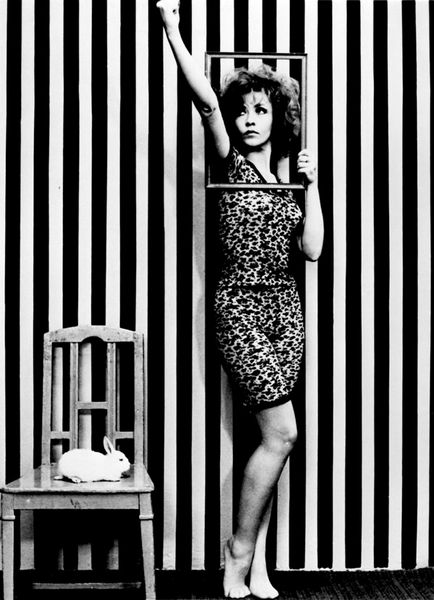

Makavejev’s film strays from Reich to investigate the wilder shores of modern sex. There is a sequence involving the once-infamous practice of “plaster casting.” Reflections by the transvestite Jackie Curtis. Poetry (bad) by Tuli Kupferberg as he stalks Manhattan streets with a toy machine-gun. And a fictional subplot about a love affair between a Yugoslavian named Milena (Milena Dravic) and the Russian figure skater Vladimir (Ivica Vidovic). After she supplies him with an orgasm, he chops off her head with one of his ice skates (“Nickel-plated Champions,” a cop says. “The finest made.”) Not to worry: Her severed head continues to speak.

To list “WR” as a great movie will stir outrage from some. “I never, in all my years of moviegoing, booed a film, no matter how bad, boring or insipid the film might have been,” wrote David Bienstock in The New York Times. “Sometimes the crime being committed in the name of cinema seemed outrageous enough to justify such a response, but I restrained myself.”

“WR” offended him principally because of its distortions of the teachings of Reich, which he felt amounted to character assassination. That Bienstock took the film as being serious about Reich, or anything else, is surprising.

“Collage,” Rosenbaum calls Makavejev’s style. Yes. Materials from anywhere come together to create whatever it is you get from it. The movie embodies the very essence of the hippie and flower-power period, which is maybe why it was a box-office hit (the nudity and X rating didn’t hurt, although there is no specifically erotic material). It is as evocative of its time as “Woodstock.” I think Makavejev’s purpose is to ridicule authorities in the areas of sex and politics (Stalin comes in for some rough sledding), and to suggest we’d get along just fine without anyone issuing us instructions in either area.

Movies like this are impossible now, unless they are made marginally, on small indie budgets. Makavejev’s own later films had stars like Roberts and Greta Scacchi, and I liked them, and they made money, but they lacked the anarchy. He hasn’t made a feature in 10 years, but is still a frequent visitor and juror at film festivals, where somehow he seems to be the host. In recent years he has taught at Harvard.

The new editions of Makavejev’s films in the Criterion Collection include fascinating supplementary material, not least a little documentary on the “improved” version of “WR.” The movie was purchased by the BBC’s Channel Four, which asked Makavejev to re-edit some of the more graphic scenes. He was happy to oblige. Key elements of the “plaster casting” scene are obscured by starbursts of psychedelic colors. And an opening nude sequence from an old silent sex film is tidied up with goldfish swimming past the crucial areas.

There is also Makavejev’s own short doc about the experience of leaving the dissolving Yugoslavia and finding himself in Hollywood. Monique Luddy, wife of the co-founder of the Telluride Film Festival, takes him to buy some trendy clothes. He looks dubiously at a colorful shirt. She encourages him: “If the producer doesn’t like you, maybe he’ll like the shirt.”

Ebert’s original reviews of “Love Affair, or the Case of the Missing Switchboard Operator,” “Innocence Unprotected,” “WR,” “Sweet Movie,” “Montenegro” and “Coca-Cola Kid” are online at rogerebert.com, along with a 1975 Makavejev interview.