There is tension between two kinds of stories in “The Red Shoes,” and that tension helps make it the most popular movie ever made about the ballet and one of the most enigmatic movies about anything. One story could be a Hollywood musical: A young ballerina falls in love with the composer of the ballet that makes her an overnight star. The other story is darker and more guarded. It involves the impresario who runs the ballet company, who demands loyalty and obedience, who is enraged when the young people get married. The motives of the ballerina and her lover are transparent. But the impresario defies analysis. In his dark eyes we read a fierce resentment. No, it is not jealousy, at least not romantic jealousy. Nothing as simple as that.

The film is voluptuous in its beauty and passionate in its storytelling. You don’t watch it, you bathe in it. Yes, the ending is a shocker, but you see it coming and there’s no way around it; the movie tells us a fairy tale and then repeats it as real life. It’s the Hans Christian Andersen fable about a young girl who puts on a pair of red slippers that will not allow her to stop dancing; she must dance and dance, in a grotesque mockery of happiness, until she is dead. This is a dire subject for a ballet, you will agree; the movie surrounds it with the hard-boiled business of running a ballet company.

“The Red Shoes” was made in 1948 by the team of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, British filmmakers as respected as Hitchcock, Reed or Lean. Powell was the director and Pressburger, a Hungarian immigrant, was the writer, but they always took a double credit as writer-directors, and were known as The Archers; their logo was an arrow hitting its target, announcing such masterpieces as “The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp,” “Black Narcissus,” “Peeping Tom,” “The Thief of Bagdad,” and “A Matter of Life and Death,” the David Niven classic that played in America as “Stairway to Heaven.”

Pressburger had written a draft of a ballet film in the 1930s, and after the war, after their enormous success with “Black Narcissus” (1947), which made a star of Deborah Kerr and won Oscars for cinematography and art direction, they had another look at it. Powell had grown up on the French Riviera; his British father ran a hotel on Cap Ferrat, and he often saw the Russian impresario Diaghilev, whose Ballets Russes wintered nearby in Monte Carlo. The Archers used Powell’s notions about Diaghilev and the earlier script to create the story of a proud, cold, distant impresario who meets his match with a fiery ballerina. Pressburger may have been inspired by a famous scandal in 1913 when Diaghilev’s great but tortured star, Vaslav Nijinsky, married the Hungarian ballerina Romola de Pulszky. He fired them both.

Casting is everything when the characters must move between realism and fantasy, and “The Red Shoes” might have failed without Moira Shearer and Anton Walbrook as the stars. Shearer and Walbrook have distinctive, even idiosyncratic personalities, and they bring an emotional realism to characters who are really, after all, only stereotypes. Walbrook plays Boris Lermontov, the imperious manager of the Ballet Lermontov, a company ruled by his iron will. He is arrogant, curt, unbending, able to charm, able to chill. Shearer plays the dancer Victoria Page, whose friend Julian Craster (Marius Goring) bursts into Lermontov’s office to complain that his composition has been stolen by the company’s conductor. Julian is hired by Lermontov, Vicky wins an audition, and when the company’s leading dancer resigns to get married, they are told “we have three weeks to create a ballet — out of nothing.”

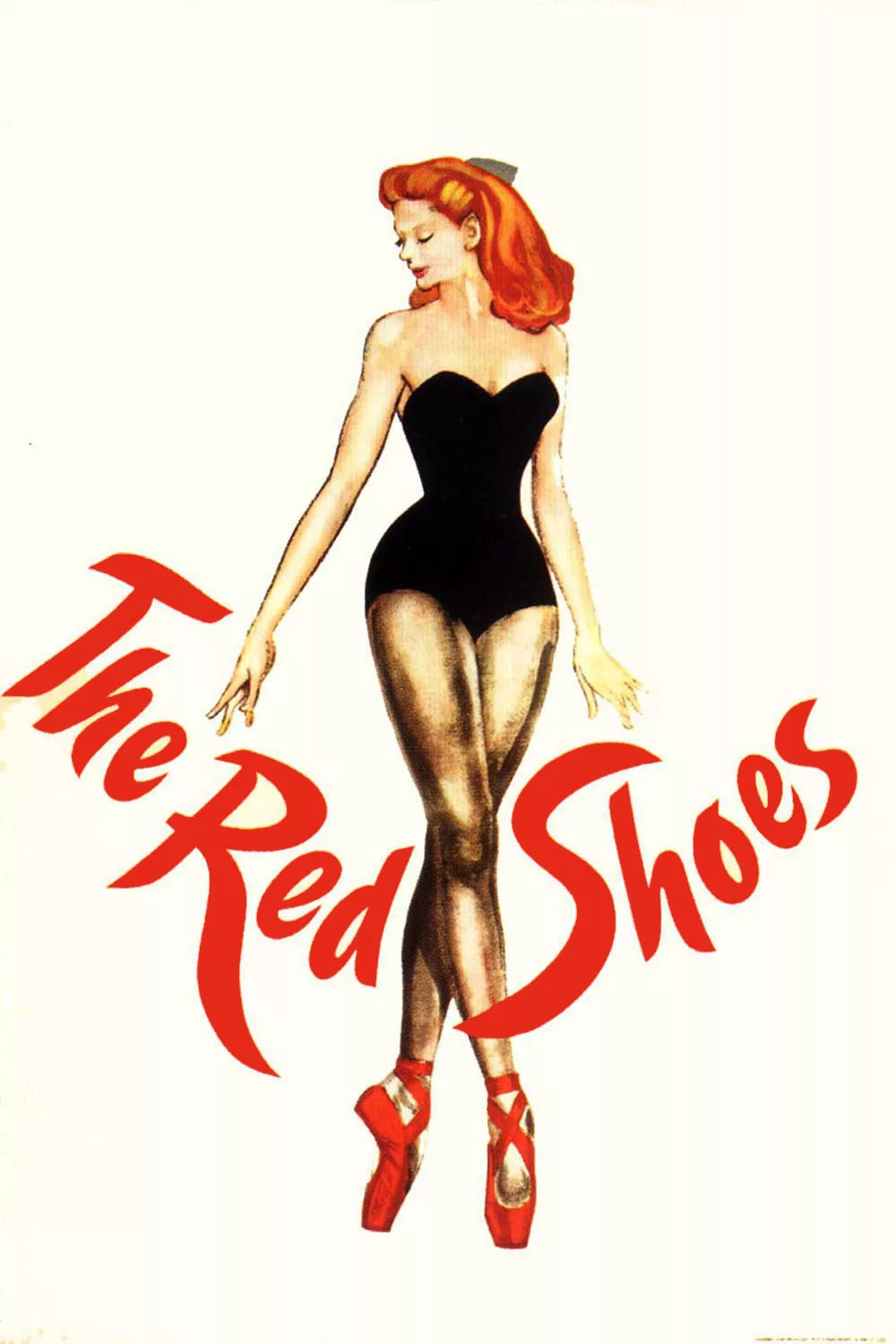

Moira Shearer, let it be said, is a great beauty: “Her cloud of red hair, as natural and beautiful as any animal’s, flamed and glittered like an autumn bonfire,” Powell wrote in his autobiography, the best ever written by a filmmaker. “She had a magnificent body. She wasn’t slim, she just didn’t have one ounce of superfluous flesh.” Of Walbrook he wrote: “Anton conceals his humility and his warm heart behind perfect manners that shield him like suit of armor. He responds to clothing like the chameleon that changes shape and color out of sympathy with its surroundings.”

Quite so. In “Colonel Blimp,” Walbrook makes a German aristocrat sympathetic. In Max Ophuls’ great “La Ronde” (1950), he is our urbane and charming guide to a decadent society. In “The Red Shoes,” he creates a deliberate enigma, a man who does not want to be understood, who imposes his will but conceals his feelings.

Vicky Page is his opposite: Joyous and open to life. Shearer, who was 21 when she was cast, was at the time with the Sadlers’ Wells Company, dancing in the shadow of the young Margot Fonteyn. She didn’t take movies seriously, waited a year before agreeing to star in “The Red Shoes,” went back to the ballet, and possibly never knew how good she was in the movie, how powerfully she related to the camera. “I never knew what a natural was before,” Powell told the studio owner J. Arthur Rank. “But now I do. It’s Moira Shearer.”

The movie tells parallel stories leading up to its 17-minute ballet sequence. While Vicky and Julian are falling in love, Lermontov and his company are creating the new ballet. There is a key scene where Lermontov and all his colleagues meet in his villa to hear Julian play the new ballet for the first time. “I was determined to shoot it in one big master shot,” Powell wrote, and it is a masterpiece of composition, of entrances, exits, approaches to the camera, background action, and the vibrating sense of a creative team at work. “There are lots of clever scenes in ‘The Red Shoes’,” he wrote, “but this is the heart of the picture.”

The other key scenes are the ballet itself, and the sequence leading up to the ending. No film had ever interrupted its story for an extended ballet before “The Red Shoes,” although its success made that a fashion, and “An American in Paris” and “Singin' in the Rain,” among others, have extended fantasy ballet sequences. None ever looked as fantastical as the one in the “The Red Shoes,” where the little shoemaker puts the fatal slippers on the girl. The physical stage is seamlessly transformed into a surreal space, where Shearer glides and flies, enters unreal landscapes and even does a pas de deux with a newspaper that takes the form of a dancer, turns into the dancer, and then into a newspaper again. The cinematographer Jack Cardiff wrote about how he manipulated camera speed to make the dancers seem to linger at the tops of their jumps; the art direction won an Oscar, mostly because of this scene (there was also an Oscar for the music, and nominations for best picture, editing and screenplay).

After Vicky and Julian are married and Lermontov fires them, he persuades her to dance “The Red Shoes” one more time. Julian walks out of the premiere of his new symphony in London to fly to Monte Carlo and accuse her of abandoning him. What will she choose? The dance, or her husband? She puts on the red slippers, and in a brilliant closeup the slippers force her to turn around, and seem to lead her as she runs from the theater and throws herself in front of a train. Discussing the script, Pressburger argued that Vicky couldn’t be wearing the red shoes when she runs away, because the ballet had not yet started. Powell writes: “I was a director, a storyteller, and I knew that she must. I didn’t try to explain it. I just did it.”

That brings us back to the tension we began with. Why does Lermontov object so violently to the marriage of these two young people? Is it sexual jealousy? Does he desire Vicky, or, for that matter, Julian? Lermontov is a bachelor with the elegant wardrobe and mannered detachment that played as gay in the 1940s, but there is not a moment when he displays any sexual feelings. He would rather die than appear vulnerable. My notion is that Lermontov is Mephistopheles. He has made a bargain with Vicky: “I will make you the greatest dancer the world has ever known.” But he warns her: “A dancer who relies upon the doubtful comforts of human love will never be a great dancer — never.” Like the Satan of classical legend, he is enraged when he wins her soul only to lose it again. He demands obedience above all else.

That leaves us with Vicky’s choice. She can return to London with Julian, or leave him and continue her career. Why does she abandon these choices at the height of her youth and beauty, and kill herself? The answer of course is that she is powerless, once she puts on the red shoes.

Reviews of “The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp” and “Peeping Tom” are in the Great Movies collection at rogerebert.com.