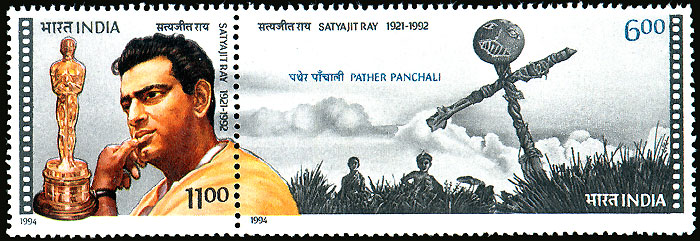

The great, sad, gentle sweep of “The Apu Trilogy” remains in the mind of the moviegoer as a promise of what film can be. Standing above fashion, it creates a world so convincing that it becomes, for a time, another life we might have lived. The three films, which were made in India by Satyajit Ray between 1950 and 1959, swept the top prizes at Cannes, Venice and London, and created a new cinema for India–whose prolific film industry had traditionally stayed within the narrow confines of swashbuckling musical romances. Never before had one man had such a decisive impact on the films of his culture.

Ray (1921-1992) was a commercial artist in Calcutta with little money and no connections when he determined to adapt a famous serial novel about the birth and young manhood of Apu–born in a rural village, formed in the holy city of Benares, educated in Calcutta, then a wanderer. The legend of the first film is inspiring; how on the first day Ray had never directed a scene, his cameraman had never photographed one, his child actors had not even been tested for their roles–and how that early footage was so impressive it won the meager financing for the rest of the film. Even the music was by a novice, Ravi Shankar, later to be famous.

The trilogy begins with “Pather Panchali,” filmed between 1950 and 1954. Here begins the story of Apu when he is a boy, living with his parents, older sister and ancient aunt in the ancestral village to which his father, a priest, has returned despite the misgivings of the practical mother. The second film, “Aparajito” (1956), follows the family to Benares, where the father makes a living from pilgrims who have come to bathe in the holy Ganges. The third film, “The World of Apu” (1959), finds Apu and his mother living with an uncle in the country; the boy does so well in school he wins a scholarship to Calcutta. He is married under extraordinary circumstances, is happy with his young bride, then crushed by the deaths of his mother and his wife. After a period of bitter drifting, he returns at last to take up the responsibility of his son.

This summary scarcely reflects the beauty and mystery of the films, which do not follow the punched-up methods of conventional biography but are told in the spirit of the English title of the first film, “The Song of the Road.” The actors who play Apu at various ages from about 6 to 29 have in common a moody, dreamy quality; Apu is not sharp, hard or cynical, but a sincere, naive idealist, motivated more by vague yearnings than concrete plans. He reflects a society that does not place ambition above all, but is philosophical, accepting, optimistic.

He is his father’s child, and in the first two films we see how his father is eternally hopeful that something will turn up–that new plans and ideas will bear fruit. It is the mother who frets about money owed the relatives, about food for the children, about the future. In her eyes, throughout all three films, we see realism and loneliness, as her husband and then her son cheerfully go away to the big city and leave her waiting and wondering.

The most extraordinary passage in the three films comes in the third, when Apu, now a college student, goes with his best friend, Pulu, to attend the wedding of Pulu’s cousin. The day has been picked because it is astrologically perfect–but the groom, when he arrives, turns out to be stark mad. The bride’s mother sends him away, but then there is an emergency, because Aparna, the bride, will be forever cursed if she does not marry on this day, and so Pulu, in desperation, turns to Apu–and Apu, having left Calcutta to attend a marriage, returns to the city as the husband of the bride.

Sharmila Tagore, who plays Aparna, was only 14 when she made the film. She projects exquisite shyness and tenderness, and we consider how odd it is to be suddenly married to a stranger. “Can you accept a life of poverty?” asks Apu, who lives in a single room and augments his scholarship with a few rupees earned in a print shop. “Yes,” she says simply, not meeting his gaze. She cries when she first arrives in Calcutta, but soon sweetness and love shine out through her eyes. Soumitra Chatterjee, who plays Apu, shares her innocent delight, and when she dies in childbirth it is the end of his innocence and, for a long time, of his hope.

The three films were photographed by Subrata Mitra, a still photographer who Ray was convinced could do the job. Starting from scratch, at first with a borrowed 16mm camera, Mitra achieves effects of extraordinary beauty: Forest paths, river vistas, the gathering clouds of the monsoon, water bugs skimming lightly over the surface of a pond. There is a fearsome scene as the mother watches over her feverish daughter while the rain and winds buffet the house, and we feel her fear and urgency as the camera dollies again and again across the small, threatened space. And a moment after a death, when the film cuts shockingly to the sudden flight of birds.

I heard a distant echo of the earliest days of the filming, perhaps, when Subrata Mitra was honored at the Hawaii Film Festival in the early 1990s, and in accepting a career award he thanked, not Satyajit Ray, but–his camera, and his film. On those first days of shooting it must have been just that simple, the hope of these beginners that their work would bear fruit.

What we sense all through “The Apu Trilogy” is a different kind of life than we are used to. The film is set in Bengal in the 1920s, when in the rural areas life was traditional and hard. Relationships were formed with those who lived close by; there is much drama over the theft of some apples from an orchard. The sight of a train, roaring at the far end of a field, represents the promise of the city and the future, and trains connect or separate the characters throughout the film, even offering at one low point a means of possible suicide.

The actors in the films have all been cast from life, to type; Italian neorealism was in vogue in the early 1950s, and Ray would have heard and agreed with the theory that everyone can play one role–himself. The most extraordinary performer in the films is Chunibala Devi, who plays the old aunt, stooped double, deeply wrinkled. She was 80 when shooting began; she had been an actress decades ago, but when Ray sought her out, she was living in a brothel, and thought he had come looking for a girl. When Apu’s mother angers at her and tells her to leave, notice the way she appears at the door of another relative, asking, “Can I stay?” She has no home, no possessions except for her clothes and a bowl, but she never seems desperate because she embodies complete acceptance.

The relationship between Apu and his mother observes truths that must exist in all cultures: how the parent makes sacrifices for years, only to see the child turn aside and move thoughtlessly away into adulthood. The mother has gone to live with a relative, as little better than a servant (“they like my cooking”), and when Apu comes to visit during a school vacation, he sleeps or loses himself in his books, answering her with monosyllables. He seems in a hurry to leave, but has second thoughts at the train station, and returns for one more day. The way the film records his stay, his departure and his return says whatever can be said about lonely parents and heedless children.

I watched “The Apu Trilogy” recently over a period of three nights, and found my thoughts returning to it during the days. It is about a time, place and culture far removed from our own, and yet it connects directly and deeply with our human feelings. It is like a prayer, affirming that this is what the cinema can be, no matter how far in our cynicism we may stray.