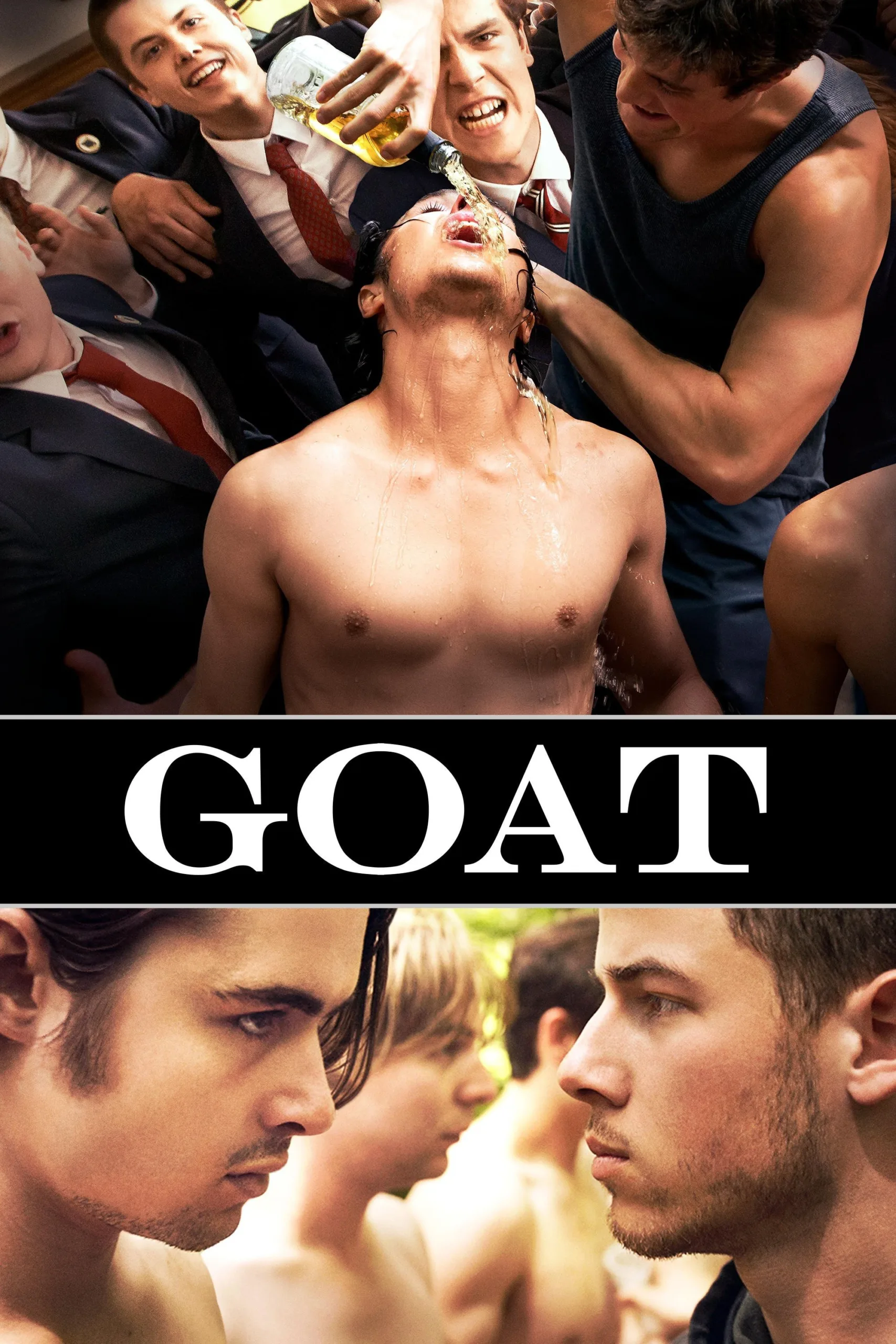

The fraternity drama “Goat” begins in a state of testosterone overload, with a long, slow-motion shot of shirtless Phi Sigma Mu brothers jumping up and down, bellowing with what could be either rage or joy. As Andrew Neel’s film unfolds, we realize there’s not a whole lot of difference.

The American “Greek” system, which indoctrinates college students into gender-segregated social clubs, polishes a middle-class version of machismo that’s proudly retrograde, and the young men of Phi Sigma Mu celebrate it. So does the film, despite its game attempt at a questioning attitude. This is a conflicted movie—far darker than the best-know recent looks at the subject, Todd Phillips’ frequently agonizing documentary “Frat House” and his doofus-y comedy “Old School,” both of which looked at their subject from the outside in rather than the other way around; but still ultimately celebratory, because the Stockholm Syndrome effect of spending so much time inside this world, experiencing it subjectively while its exemplars shout the organization’s values at the hero, gets us invested in seeing the world continue and its values be perpetuated.

The film’s hazing scenes evoke the boot camp sequences in “Full Metal Jacket” but without the merciless coldness, because the film’s hero, Brad (newcomer Ben Schnetzer, in a career-making star turn) desperately wants to belong to the organization. The price of admission is enduring Hell Week, a seven-day stretch of hazing that leads up to initiation; activities include punitive drinking, assorted forms of psychological and emotional abuse, a mock rape, and a scene of a pledge being bombarded with rotten fruit that ends very, very badly.

If anyone should avoid such a twisted brand of silliness, it’s Brad. Mere weeks before entering the pledge program, he survived a mugging that ended in a savage, prolonged beating. He’s suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder that’s bound to be set off by Hell Week. But he wants to feel protected and supported—which is the reason so many young men join these groups, this author included; I was a Kappa Sigma in college thirty years ago—and from a distance, the bonds of brotherhood seem to offer the kind of emotional safety net he needs at that point in his life. Brad probably wouldn’t be there if his older brother Brett (Nick Jonas, the youngest Jonas brother) weren’t already a member. Brett is the “cool” one of the two, a confident party monster who navigates the frat’s sealed-off world of boozing and random sex like a lifer in a war movie.

Co-written by David Gordon Green, Neel and Mike Roberts, and based on Brad Land’s same-titled expose of a real case in Ohio, “Goat” does a mostly admirable job of presenting the grim shenanigans of Phi Sigma Mu as rituals: toothless college-boy approximations of the more violent and sadistic rituals that soldiers participate in while they’re being conditioned for war. But there are a couple of crippling problems here, and they prevent the movie from really cohering into a statement instead of an alternately harrowing and absurd experience.

One problem is the screenplay’s omissions. We rarely get a sense of the frat house in relation to the campus and the community that surrounds it; this helps to cement a slightly dreamy atmosphere and intensify the action (they might as well be on a desert island like the kids in “Lord of the Flies”) but it also deprives us of a sense of the world beyond the fraternity house, so we naturally end up wanting Brad to get through initiation and prove himself to Brett and the other brothers. This approach also contributes to the sense that the brothers and pledges are willingly entering into a world largely devoid of women, which feels true to the reality of Greek life inside a frat house; but the film pays scant attention to women as anything other than random sex partners, girlfriends and background color (the hero enjoys one brief kiss with a former high school crush who pretty much vanishes from the story after that), so the film’s perspective ends up endorsing the values that it seems, in the abstract anyway, to want to critique. Also missing in action are parents, whose alternately disapproving and celebratory perspective on the traditions of Greek life might’ve added ballast to the film.

A larger problem is the hero’s specific predicament. While it’s definitely a bad idea for a young man to pledge to a fraternity shortly after surviving a beating, it’s probably not a good idea to do anything else that’s physically demanding and psychologically grueling, either, especially if it involves sensory deprivation or being yelled at or pushed around. Whether Brad would’ve gotten through Hell Week without a hitch had he pledged a couple of years later, after he’d had time to process his mugging, is a question the movie never thinks to asks. When I was in college I had a slightly older friend who pledged to a different fraternity after being discharged from the Army, and he got through it fine, because after what he’d been through in the military, the college campus facsimile seemed like a joke. During a sensory deprivation exercise where his pledge class sat with hoods over their heads in the dark for three hours while music blasted at earsplitting volume, he took a nice, long nap. That anecdote isn’t offered to minimize any of the behavior depicted in “Goat,” only to suggest that the inappropriateness of Brad’s decision to pledge often seems like a matter of bad timing here, which surely wasn’t the point.

There’s still a lot to chew on after seeing “Goat”—in particular the question of why organizations that are essentially incubators for the most retrograde ideas about manhood are still allowed to exist at institutions theoretically dedicated to enlightenment—but any discussion of toxic masculinity, or the ways in which brotherhood in all its forms can get twisted, is likely to be muted by second-guessing of the movie’s methods.