Anyone with even a passing familiarity with the irrepressible personality of Broadway legend Elaine Stritch will be unsurprised to find her caustic wit and room-commanding charisma front-and-center in Chiemi Karasawa’s “Elaine Stritch: Shoot Me,” but what elevates the film is its subject’s willingness to reveal a more fragile side in her later years. As she rehearses for a one-woman show built around the music of Stephen Sondheim, manages her diabetes, reminisces about her past loves and career choices for the camera, a complete picture of a resilient artist comes into focus. As she reaches a point in her life, at the age of 86, in which she starts to reflect on “the picture you’re going to leave,” Stritch is a documentary subject as fearless and raw as her stage persona.

“Elaine Stritch: Shoot Me” (and the generic title really is the worst thing about the film) opens with its subject holding court in a city in which she’s recognized on every corner. Proudly strutting the New York City streets, in full-length fur, waving sunglasses in one hand and a coffee cup in the other, Stritch is the Queen of Broadway, where she first appeared in 1944. Largely through still photographs actually being held by Stritch, the filmmaker hits a few of the key moments in Stritch’s career—her early stage years, romance with Ben Gazzara, work on “30 Rock,” and earth-shattering performance in “Company,” for example—but spends most of the film’s running time in the moment. This is not a retrospective film by any stretch, focusing as much on how Stritch struggles to maintain focus and overcome health and addiction issues in preparation for yet another show.

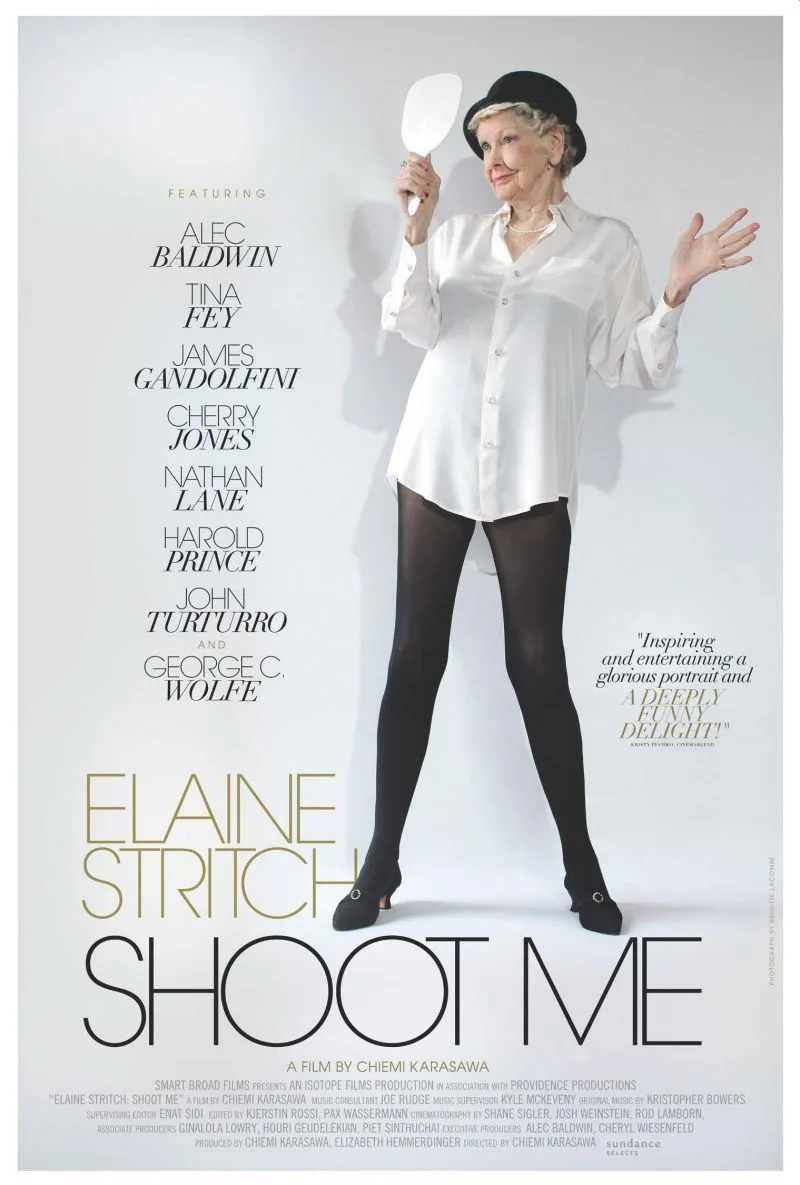

Karasawa does allow for a few bits of talking-head insight from Stritch collaborators past and present, including Nathan Lane, George C. Wolfe, Tina Fey, and, in a bittersweet moment, James Gandolfini (to whom the film is dedicated post-credits). They all express a degree of awe when it comes to Elaine Stritch’s talent and work ethic but the underlying theme of most of “Shoot Me” is that of humanizing a woman who has become larger than life for theatre lovers. Stritch truly struggles with lyrics as she prepares for the show, has difficulty maintaining her blood sugar, battles a decades-long addiction to alcohol, and clearly worries that she may not be able to do what she loves much longer. In fact, she seems to know that she should hang it up and yet can’t bring herself to do it. She talks about the Sondheim show like it’s her last and then starts brainstorming another one built around the work of Elton John.

What emerges from “Elaine Stritch: Shoot Me” is a portrait of a woman who has perhaps always balanced a healthy degree of fear with her external display of confidence. Great artists often come from a position of being afraid of disappointing someone; in Stritch’s case, the people she had the tightest relationship with–her audience. And as lyrics become more difficult to remember and trips to the hospital increase, that fear grows, almost driving Stritch to work even harder. To see such a vibrant, powerful personality as Elaine Stritch stripped away of all artifice and saying things like “I’m getting scared” has an incredible emotional quotient.

Ultimately, “Elaine Stritch: Shoot Me” borders on inspirational in the way that it humanizes someone this undeniably talented and successful. She fears old age and failure as much as anyone. We all do. After all, as her husband used to say in one of Elaine’s favorite phrases, “Everybody’s got a sack of rocks.” And, everyone, even a person as amazingly talented and successful as Elaine Stritch worries about the picture they’re going to leave.