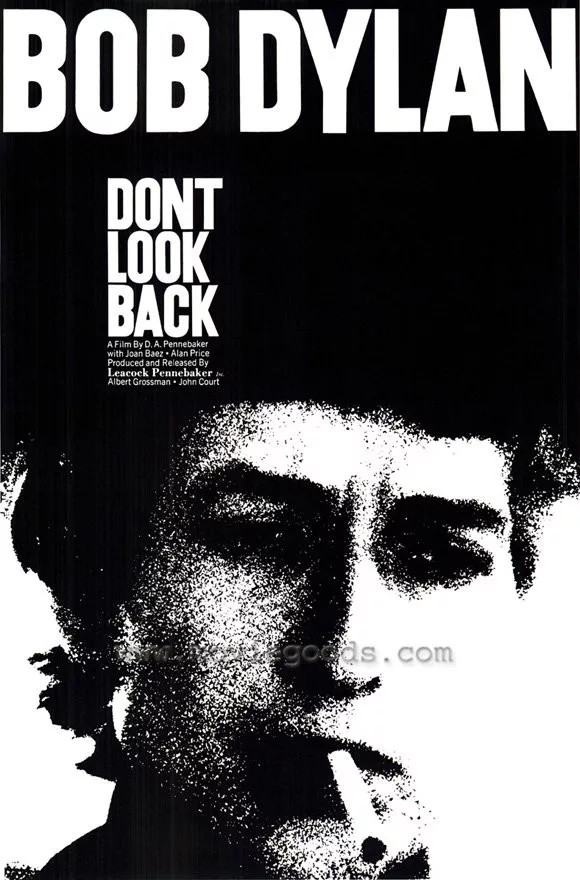

What a jerk Bob Dylan was in 1965. What an immature, self-important, inflated, cruel, shallow little creature, lacking in empathy and contemptuous of anyone who was not himself or his lackey. Did we actually once take this twirp as our folk god? I scribbled down these observations as I watched the newly restored print of “Don’t Look Back,” the 1967 documentary about Dylan’s 1965 concert tour of England. And I was asking myself: Surely I didn’t fall for this at the time? I tried to remember the review I wrote when the movie was new. Was I so much under the Dylan spell that I couldn’t see his weakness of character? Take the two scenes where he mercilessly puts down a couple of hardworking interviewers, who are only trying to do their job (i.e., give Dylan more publicity), while a roomful of Dylan yes-men, groupies and foot-kissers join in the jeers. I was chilled by the possibility that I reacted to these scenes differently the first time around, falling for Dylan’s rude and nearly illiterate word games as he pontificates about “truth.” I hurried home and burrowed into my files for the 1967 review of “Don’t Look Back,” and was relieved to discover that, even then, I had my senses about me. “Those who consider Dylan a lone, ethical figure standing up against the phonies will discover after seeing this film,” I wrote, “that they have lost their hero. Dylan reveals himself, alas, to have clay feet like all the rest of us. He is immature, petty, vindictive, lacking a sense of humor, overly impressed with his own importance and not very bright.” Thank God I was not deceived. I gave the movie three stars, and still do, for its alarming insights.

Of course there is the music. Always the music. I’m listening to “Highway 61 Revisited” as I write these words. I like his music, and I like his whiny, nasal delivery; it speaks to the eternal misunderstood complainer in all of us. I remember the thrill we all felt as undergraduates when we first heard “Blowing in the Wind.” At the time we thought we were the Answer, my friends. But we were young, and hadn’t seen this movie.

As a musician, Dylan has endured and triumphed. Perhaps he has also grown and matured as a human being, and is today a nice guy with an infectious sense of humor and soft-spoken modesty. Or maybe not. I don’t know. What I do know is that D.A. Pennebaker’s 1967 film, which invented the rock documentary, is a time capsule from the period when Sgt. Pepper was steamrolling Mr. Tambourine Man. “You don’t ask the Beatles those questions, do you?” Dylan says to one reporter. To which the only possible answer was, Bob, you just don’t know the half of it.

Another irony is that a true folk goddess, Joan Baez, with her remarkable voice, presence and soul, tags along during the early scenes, barely acknowledged by Dylan. She brings the film to a glow by singing “Love Is a Four-Letter Word” in a hotel room one night, and then disappears from the film, unremarked. My guess is that she’d had enough.

The movie is like a low-rent version of the rock concert documentaries that would follow. Dylan is badgered by a room full of journalists at a press conference–but it’s a small room, with only half a dozen reporters. He insults them, lacking the Beatles’ saving grace of wit. He’s mobbed by fans–hundreds, not thousands. He fills Royal Albert Hall, not Wembley Stadium. He reminds me of that mouse floating down the Chicago River on its back, signaling for the drawbridge to be raised.

Sometimes you simply cannot imagine what he, or the filmmakers, were thinking. “How did you start?” he’s asked at a press conference. Cut to a scene in a Southern cotton field. Dylan stands in front of a pickup truck with some old black field hands sitting on it. He sings a song. Are we supposed to think he rode the rails and bummed in hobo jungles and felt proletarian solidarity with the workers, like Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger or Ramblin’ Jack Elliott? I was reminded of Steve Martin in “The Jerk,” saying “I was born a poor black child.” The field hands break into grateful applause, as the scene dissolves into a thunderous London concert ovation. Give us a break.

If Dylan sees this re-release, I hope he cringes. We were all callow once, but it is a curable condition. A guy from Time magazine comes to interview him. “I know more about what you do just by looking at you than you’ll ever be able to know about me,” Dylan tells him, little suspecting how much we know just by looking at him. He suggests that the magazine try printing the truth. And what would that be? “A photo of a tramp vomiting into a sewer, and next to it a picture of Rockefeller,” suggests the man described in a recent review as “one of the most significant artists of the second half of the 20th century.” Significance I will grant him. More than we knew.