In a movie named “The Five Obstructions,” the Danish director Lars von Trier creates an ordeal for his mentor, Jorgen Leth. The older director will have to remake a short film in five different ways, involving five obstructions which von Trier will devise. One of the five involves making a film in “the most miserable place on Earth,” which they decide is the red light district of Mumbai. The director is unable to deal with this assignment. Now here is a documentary made in a place which is by definition as miserable: The red light district of Calcutta. I thought of the Danish film as I was watching this one, because the makers of “Born Into Brothels: Calcutta’s Red Light Kids” also find it almost impossible to make. They are shooting in an area where no one wants to be photographed, where lives are hidden behind doors or curtains, where with their Western features and cameras they are as obvious as the police, and indeed suspected of working for them.

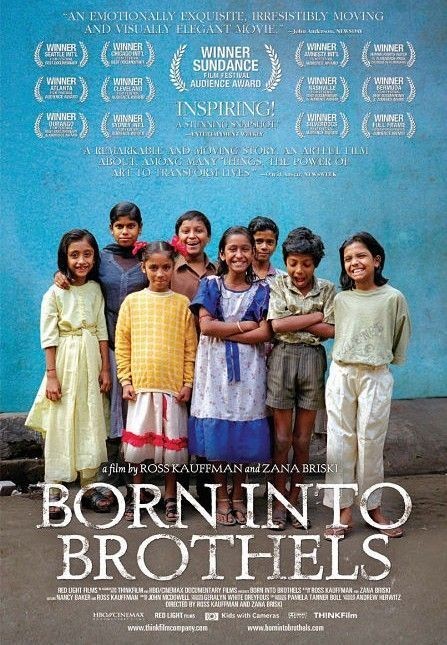

Zana Briski, an American photographer, and Ross Kauffman, her collaborator, went to Calcutta to film prostitution and found that it melted out of sight as they appeared. It was all around them, it put them in danger, but it was invisible to their camera. What they did see were the children, because the kids of the district followed the visitors, fascinated. Briski hit upon the idea of giving cameras to these children of prostitutes, and asking them to take photos of the world in which they lived.

It is a productive idea, and has a precedent of sorts in a 1993 project by National Public Radio in Chicago; two teenagers, LeAlan Jones and Lloyd Newman, were given tape recorders and asked to make an audio documentary of the Ida B. Wells public housing project, where they lived and where a young child had been thrown from a high window in a fight over candy. Their work won a Peabody Award.

The kids in “Born Into Brothels” (which is one of this year’s Oscar nominees) take photos with zest and imagination, squint at the contact sheets to choose their favorite shots, and mark them with crayons. Their pictures capture life, and a kind of beauty and squalor that depend on each other. One child, Avijit, is so gifted he wins a week’s trip to Amsterdam for an exhibition of photography by children.

Over a couple of years, Briski teaches photo classes and meets some of the parents of the children — made difficult because she must work through interpreters. Prostitution in this district is not a choice but a settled way of life. We meet a grandmother, mother and daughter all engaged in prostitution, and the granddaughter seems destined to join them. Curiously, the movie does not suggest that the boys will also be used as prostitutes, although it seems inevitable. The age of entry into prostitution seems to be puberty. There are no scenes that could be described as sexually explicit, partly because of the filmmakers’ tact in not wanting to exploit their subjects, partly no doubt because the prostitutes refused to be filmed except in innocuous settings.

Briski becomes determined to get several of the children out of the district and into a boarding school, where they will have a chance at different lives. She encounters opposition from their parents and roadblocks from the Indian bureaucracy, which seems to create jobs by requiring the same piece of paper to be meaninglessly stamped, marked, read or filed in countless different offices. She goes almost mad trying to get a passport for Avijit, the winner of the Amsterdam trip; of course with his background he lacks the “required” papers.

The film is narrated mostly by Briski, who is a good teacher and brings out the innate intelligence of the children as they use their cameras to see their world in a different way. The faces of the children are heartbreaking, because we reflect that in the time since the film was finished, most of them have lost childhood forever, some their lives. Far away offscreen is the prosperous India with middle-class enclaves, an executive class and a booming economy. These wretched poor exist in a separate and parallel universe, without an exit.

The movie is a record by well-meaning people who try to make a difference for the better, and succeed to a small degree while all around them the horror continues unaffected. Yes, a few children stay in boarding schools. Others are taken out by their parents, drop out, or are asked to leave. The red light district has existed for centuries and will exist for centuries more. I was reminded of a scene in Bunuel’s “Viridiana.” A man is disturbed by the sight of a dog tied to a wagon and being dragged along faster than it can run. The man buys the dog to free it, but does not notice, in the background, another cart pulling another dog.