* Ebert’s Note: “Beyond the Valley of the Dolls,” a movie for which I wrote the screenplay in 1969, has over the years become a cult film. Although it would not be appropriate for me to review it or give it a star rating, I offer the following observations written for Film Comment magazine on the occasion of the movie’s 10th anniversary in 1980.

Remembered after 10 years, “Beyond the Valley of the Dolls” seems more and more like a movie that got made by accident when the lunatics took over the asylum. At the time Russ Meyer and I were working on “BVD” I didn’t really understand how unusual the project was. But in hindsight I can recognize that the conditions of its making were almost miraculous. An independent X-rated filmmaker and an inexperienced screenwriter were brought into a major studio and given carte blanche to turn out a satire of one of the studio’s own hits. And “BVC” was made at a time when the studio’s own fortunes were so low that the movie was seen almost fatalistically, as a gamble that none of the studio executives really wanted to think about, so that there was a minimum of supervision (or even cognizance) from the Front Office.

We wrote the screenplay in six weeks flat, laughing maniacally from time to time, and then the movie was made. Whatever its faults or virtues, “Beyond the Valley of the Dolls” is an original — a satire of Hollywood conventions, genres, situations, dialogue, characters and success formulas, heavily overlaid with such shocking violence that some critics didn’t know whether the movie “knew” it was a comedy.

Although Meyer had been signed to a three-picture deal by 20th Century-Fox, I wonder whether at some level he didn’t suspect that “BVD” would be his best shot at employing all the resources of a big studio at the service of his own highly personal vision, his world of libidinous, simplistic creatures who inhabit a pop universe. Meyer wanted everything in the screenplay except the kitchen sink. The movie, he theorized, should simultaneously be a satire, a serious melodrama, a rock musical, a comedy, a violent exploitation picture, a skin flick and a moralistic expose (so soon after the Sharon Tate murders) of what the opening crawl called “the oft-times nightmarish world of Show Business.”

What was the correct acting style for such a hybrid? Meyer directed his actors with a poker face, solemnly, discussing the motivations behind each scene. Some of the actors asked me whether their dialogue wasn’t supposed to be humorous, but Meyer discussed it so seriously with them that they hesitated to risk offending him by voicing such a suggestion. The result is that “BVD” has a curious tone all of its own. There have been movies in which the actors played straight knowing they were in satires, and movies which were unintentionally funny because they were so bad or camp. But the tone of “BVD” comes from actors directed at right angles to the material. “If the actors perform as if they know they have funny lines, it won’t work,” Meyer said, and he was right.

The movie was inspired only incidentally by “Valley of the Dolls.” Neither Meyer nor I ever read Jacqueline Susann’s book, but we did screen the Mark Robson film, and we took the same formula: Three young girls come to Hollywood, find fame and fortune, are threatened by sex, violence and drugs, and either do or not do win redemption.

The original book was a roman a clef, and so was “BVD,” with an important difference: We wanted the movie to seem like a fictionalized expose of real people, but we personally possessed no real information to use as inspiration for the characters. The character of teenage rock tycoon Ronnie “Z-Man” Barzell, for example, was supposed to be “inspired” by Phil Spector — but neither Meyer nor I had ever met Spector.

The movie’s story was made up as we went along, which makes subsequent analysis a little tricky. Not long ago, for example, I was invited up to Syracuse University to discuss Meyer’s work, and the subject of Z-Man came up. (Readers who have seen “BVD” will know that Z-Man is a rock Svengali who seems to be a gay man for most of the movie, but is finally revealed to be a woman in drag.) Some of the questions at Syracuse dealt with the “meaning” of Z-Man’s earlier scenes, in light of what is later discovered about the character. But in fact those earlier scenes were written before either Meyer or I knew Z-Man was a transvestite: that plot development came on the spur of the moment. So, too, did such inspirations as quoting a “Citizen Kane” camera movement from a stage below to a catwalk above, or the use of the Fox musical fanfare during the beheading sequence.

They asked at Syracuse if Meyer’s use of the Fox trademark music was a put-down of the studio system. Meyer’s motive was much more basic: By using the music, he hoped to establish a satiric tone to the scene that would moderate the effect of the beheading and help protect against an X rating.

In the event, of course, “Beyond the Valley of the Dolls” was rated X anyway. There is a story about that. If the movie were to be rated today, it would probably get an R rating with a few small cuts. It was a very mild X. That was because Meyer and the studio were aiming for the R rating. When they didn’t get it, Meyer believed the ratings board had felt obligated to give the “King of the Nudies” an X rating, lest it seem to endorse his movie to the Majors.

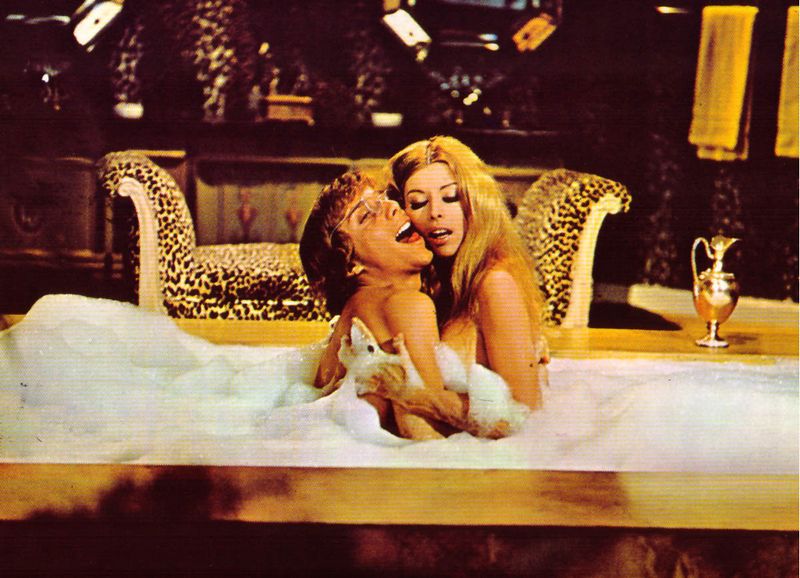

Because the movie was stuck with the X, Meyer wanted to re-edit certain scenes in order to include more nudity (he shot many scenes in both X and R versions). But the studio, still in the middle of a cash-flow crisis, wanted to rush the film into release. Meyer still waxes nostalgic for the “real” X version of BVD, which exists only in his memory but includes many much steamier scenes starring the movie’s many astonishingly beautiful heroines and villianesses.

The visit to Syracuse was a chance for me to see BVD again for the first time in a few years. The movie still seems to play for audiences; it hasn’t dated, apart from the rather old-fashioned narrative quality it had even at the time of its release. It begins rather slowly, because so many characters have to be established and such an ungainly plot has to be set in motion. (The story is such a labyrinthine juggling act that resolving it took a quadruple murder, a narrative summary, a triple wedding and an epilogue.) But the last hour has a real kinetic energy, and the scenes beginning with Z-Man’s psychedelic orgy and ending with his death are, I must say on Meyer’s behalf, as exciting, terrifying and dynamic as any such sequence I can remember. That stretch of “BVD” is pure cinema, combining shameless melodrama, highly charged images of violence, sledge-hammer editing and musical overkill. It works.

And the movie as a whole? I think of it as an essay on our generic expectations. It’s an anthology of stock situations, characters, dialogue, clichés and stereotypes, set to music and manipulated to work as exposition and satire at the same time; it’s cause and effect, a wind-up machine to generate emotions, pure movie without message. The strange thing about the movie is that it continues to play successfully to completely different audiences for different reasons. When Meyer and I were hired a few years later to work on an ill-fated Sex Pistols movie called “Who Killed Bambi?” we were both a little nonplussed, I think, to hear Johnny Rotten explain that he liked “Beyond the Valley of the Dolls” because it was so true to life.