Sidney Lumet‘s “Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead” is such a superb crime melodrama that I almost want to leave it at that. To just stop writing right now and advise you to go out and see it as soon as you can. I so much want to avoid revealing plot points that I don’t even want to risk my usual strategy of oblique hints. You deserve to walk into this one cold.

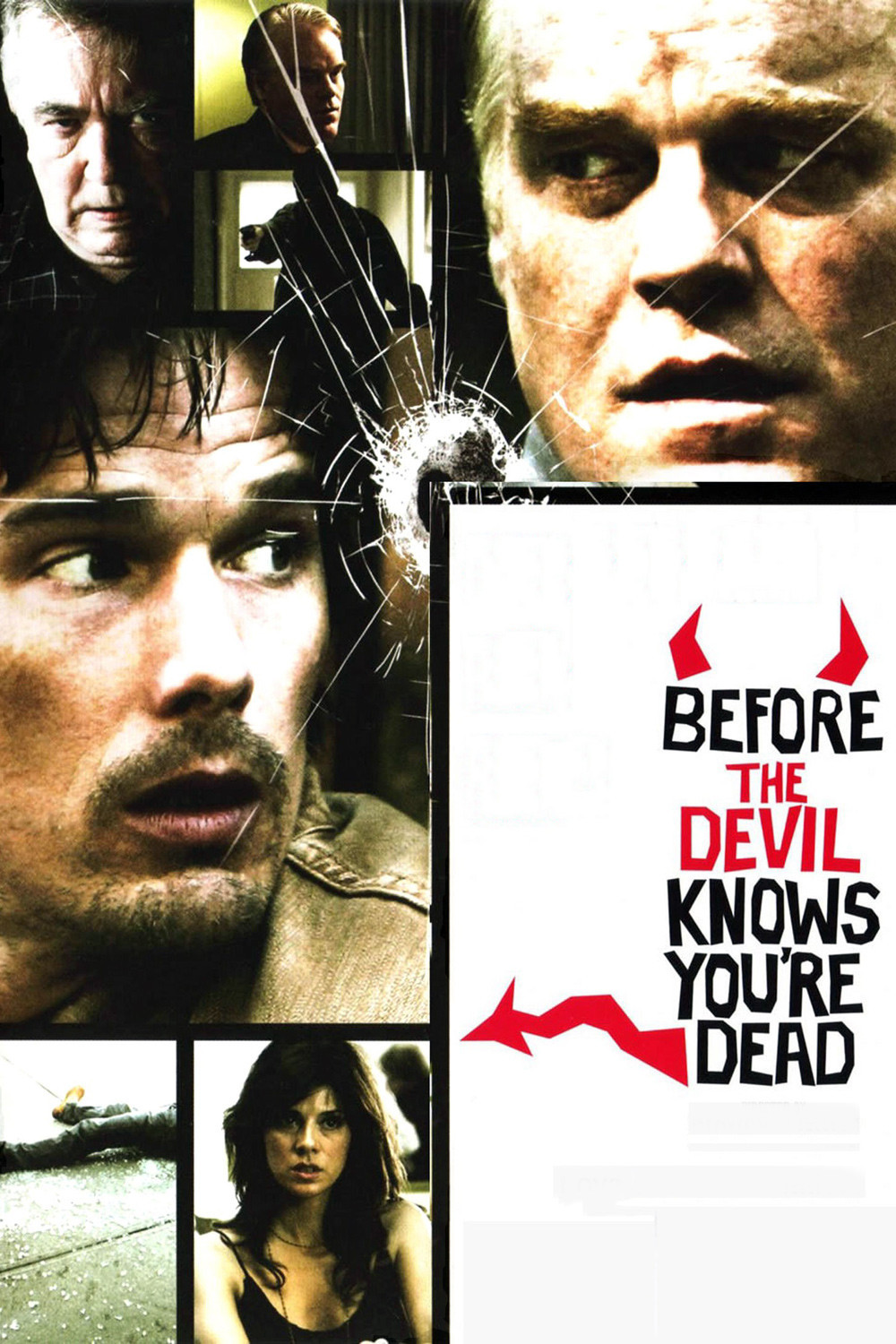

Yet that would prevent my praise, and there is so much to praise about this film. Let me try to word this carefully. The movie stars Philip Seymour Hoffman and Ethan Hawke as brothers — yes, brothers, because although they may not look related, they always feel as if they share a long and fraught history. Hoffman plays Andy, a payroll executive who dresses well and always has every hair slicked into place, but has a bad drug habit and an urgent need to raise some cash. Hawke plays Hank, much lower on the financial totem pole, with his own reasons for needing money; he can’t face his little girl and admit he can’t afford to pay for her class outing to attend “The Lion King.” Hank looks more like the druggie, but you never can tell.

Andy suggests they solve their problems by robbing a jewelry store. And not just any jewelry store, but find out for yourself. He has it all mapped out as a victimless crime: They won’t use guns, they’ll hit early Saturday when the shopping mall doesn’t have customers, the store’s losses will be covered by insurance, and so on. Sounds good on paper, before everything goes wrong. And that’s when the movie becomes intense and emotionally devastating.

These two brothers are capable of feeling emotions rare in modern crime films: grief and remorse. They cave in with regret. And they still need money; Andy learns that when you are heartbroken it is bad enough, but even worse when your legs may be broken, too. Meanwhile, their dozy father (Albert Finney) starts looking into the case himself, and that leads to a conversation with one son that Eugene O'Neill couldn’t have written any better.

The movie fully establishes the families involved. Finney has been married forever to Rosemary Harris, and still loves her to pieces. Hoffman is married to Marisa Tomei, who just keeps on getting sexier as she grows older so very slowly. Hawke is divorced from Amy Ryan, who would happily see him in jail for non-payment of child support. Although the film opens with Hoffman and Tomei ecstatically making love in Rio (say what you will about the big guy, Hoffman looks to be an energetic and capable lover), their marriage is far from perfect.

The Japanese name some of their artists Living Treasures. Sidney Lumet is one of ours. He has made more great pictures than most directors have made pictures, and found time to make some clunkers on the side. Here he takes a story that is, after all, pretty straightforward, and tells it in an ingenious style we might call narrative interruptus. The brilliant debut screenplay by Kelly Masterson takes us up to a certain point, then flashes back to before that point, then catches us up again, then doubles back, so that it meticulously reconstructs how spectacularly and inevitably this perfect crime went wrong.

And it doesn’t simply go wrong, it goes wrong with an aftermath we care about. This isn’t a movie where the crime is only a plot, and dead bodies are only plot devices. Its story has deeply emotional consequences. That’s why an actor with Albert Finney’s depth is needed for an apparently supporting role. If he isn’t there when he’s needed, the whole film loses. As for Hoffman and Hawke, so seemingly different but such intelligent actors, they pull off that miracle that makes us stop thinking of anything we know about them, and start thinking only of Andy and Hank.

This is a movie, I promise you, that grabs you and won’t let you think of anything else. It’s wonderful when a director like Lumet wins a Lifetime Achievement Oscar at 80, and three years later makes one of his greatest achievements.