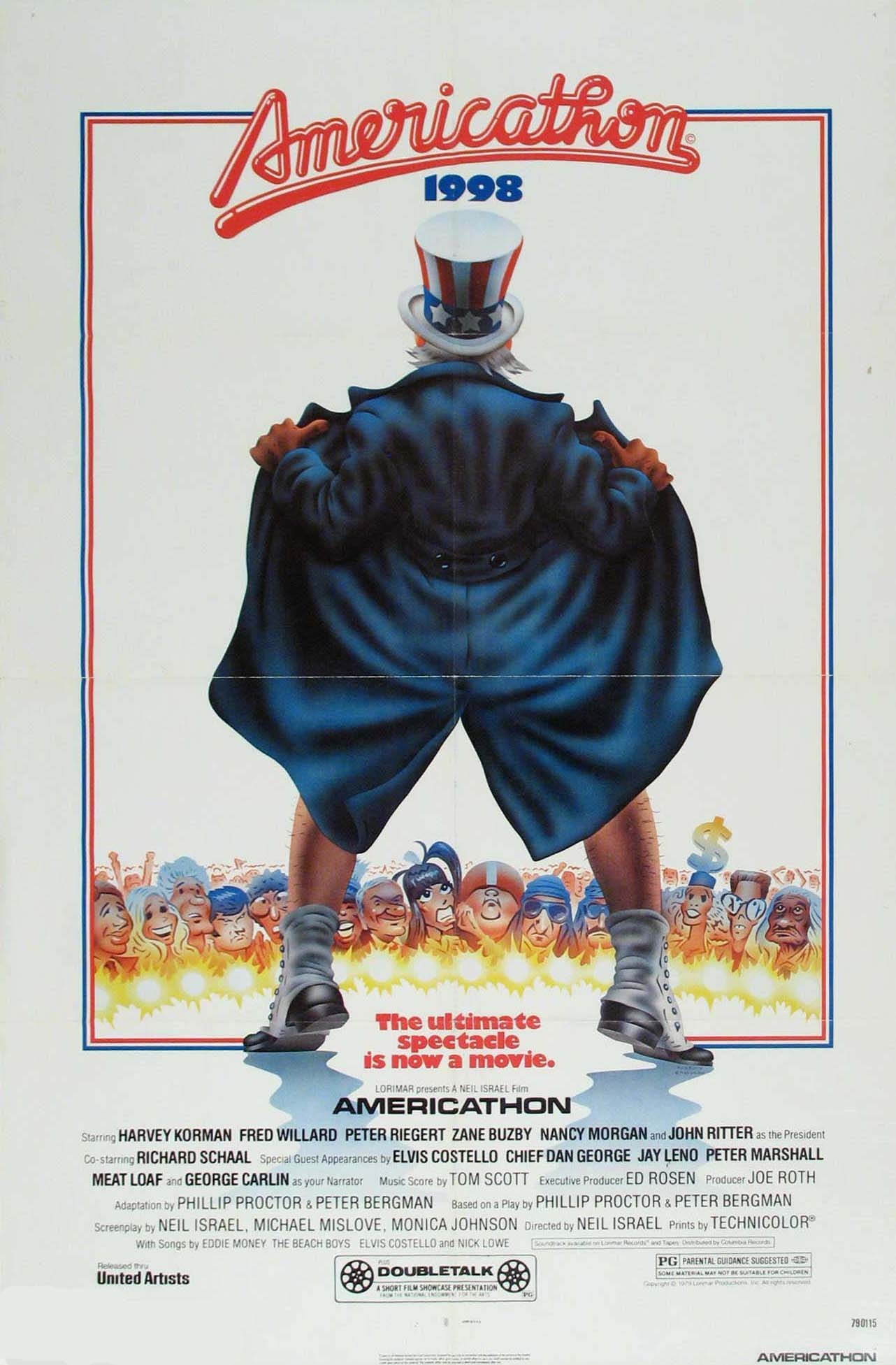

“Americathon” is a puerile exploitation of one very thin joke during 98 very long minutes. It is accompanied by a short subject that is part of the National Endowment for the Arts’ new project to get shorts into movie theaters. If their shorts continue to be played with features like “Americathon,” they will, alas, still remain unseen.

The movie’s about America in 1998, when the gas shortage has completely eliminated the auto, except as a possession you can park permanently and live in. Bicycling and jogging and roller-skating are the means of transportation, and the country is in hock for $400 billion to an ancient Indian (Chief Dan George) who’s cornered the roller-skate market.

What to do? Better still, how to care about an idea that might stretch to a four-minute sketch but hardly to feature length? The challenge had to be faced by director Neil Israel, whose previous credits include “Tunnelvision.” That movie had a Procter and Bergman sketch in it about a charity marathon to save New York. Why not, Israel asked, make a whole movie about a marathon to save America?

He has. And he’s overpopulated his movie with hundreds of comic characters: a berserk master of ceremonies and a lustful President and the usual would-be zany presidential advisers. A lot of this movie feels directly but not cleverly ripped off from “Putney Swope” and the deservedly obscure “The Virgin President.” There are “jokes” involving a government computer that casts the Americathon with dozens of ventriloquists, and about Chinese fast-food stands and warring Arabs and sexy double agents from Vietnam.

But mostly what we get is hysteria. Israel’s idea of a comic scene is to jam his screen with people in funny costumes and have them run around and scream at the top of their lungs. He has not yet discovered the most basic rule of comedy, which is that people are not necessarily funny because they act funny; they’re funny when the way they act seems funny to us, or funny through the story’s logical vision. W. C. Fields never acted “funny.” He behaved always with the utmost self-concentration.

One of the ways in which “Americathon” achieves a horrible fascination, however, is in its absolute consistency: There is hardly a single species of comic business that Israel doesn’t demonstrate he is incompetent to handle. He underlines puns. He picks the wrong angle to shoot the scene where the vain hero loses his toupee. He shoots the midget tap-dancers in extra-long shot, and puts the uncoordinated marching bands on TV monitors, so they just look like regular marching bands, and he lets his actors look like they’re having a good time acting so crazily, when in fact they’d be infinitely funnier if they projected a studied, dim intensity.

Scrutinize this movie closely and you will observe, here and there on the screen, actors attempting bits of comic business which must have seemed funny to them at the time, but which the camera placement and editing have lost or obscured. The movie is also very badly lit — astonishing, since cinematographer Gerald Hirschfeld’s credits include even the difficult but beautiful black-and-white work in “Young Frankenstein.”

If you plan to miss this movie, better miss it quickly; I doubt if it’ll be around to miss for long.