Apart from the detail that he was a heroin dealer, Frank Lucas’ career would be an ideal case study for a business school. “American Gangster” tells his success story. Inheriting a crime empire from his famous boss Bumpy Johnson, he cornered the New York drug trade with admirable capitalist strategies. He personally flew to Southeast Asia to buy his product directly from the suppliers, used an ingenious importing scheme to get it into the United States, and sold it at higher purity and lower cost than anyone else was able to. At the end, he was worth more than $150 million, and got a reduced sentence by cutting a deal to expose three-quarters of the NYPD narcotics officers as corrupt. And he always took his mom to church on Sunday.

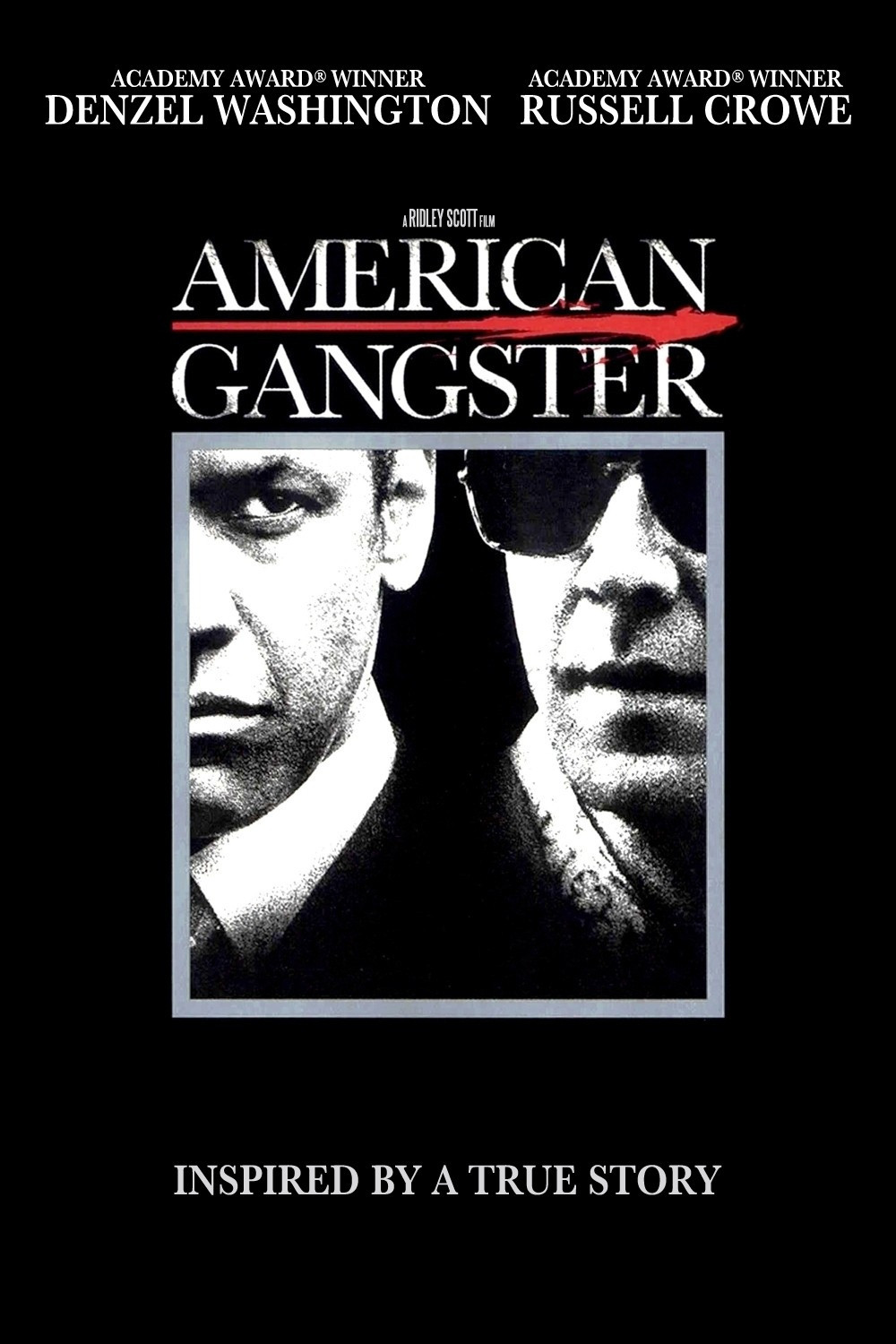

Lucas is played by Denzel Washington in another one of those performances where he is affable and smooth on the outside, yet ruthless enough to set an enemy on fire. Here’s a detail: As the man goes up in flames, Frank shoots him to put him out of his agony. Now that’s merciful. His stubborn antagonist in the picture is a police detective named Richie Roberts (Russell Crowe), who gets a very bad reputation in the department. How does he do that? By finding $1 million in drug money — and turning it in. What the hell kind of a thing is that to do, when the usual practice would be to share it with the boys?

There is something inside Roberts that will not bend, not even when his powerful colleague (Josh Brolin) threatens him. He vows to bring down Frank Lucas, and he does, although it isn’t easy, and his most troubling opposition comes from within the police. Lucas, the student of the late Bumpy, has a simple credo: Treat people right, keep a low profile, adhere to sound business practices and hand out turkeys on Thanksgiving. He can trust the people who work for him because he pays them very well and many of them are his relatives.

In the movie, at least, Lucas is low-key and soft-spoken. No rings on his fingers, no gold around his neck, no spinners on his hubcaps, with a quiet marriage to a sweet wife and a Brooks Brothers image. It takes the authorities the longest time to figure out who he is, because they can’t believe an African American could hijack the Harlem drug trade from the Mafia. The Mafia can’t believe it, either, but Frank not only pulls it off, but is still alive at the end.

When it was first announced, Ridley Scott’s film was inevitably called “The Black Godfather.” Not really. For one thing, it tells two parallel stories, not one, and it really has to, because without Roberts, there would be no story to tell, and Lucas might still be in business.

But that doesn’t save us from a stock female character who is becoming increasingly tiresome in the movies, the wife (Carla Gugino) who wants Roberts to choose between his job and his family. Their obligatory scenes together are recycled from a dozen or a hundred other plots, and although we sympathize with her (will they all be targeted for assassination?), we grow restless during her complaints. Roberts’ domestic crisis is not what the movie is about.

It is about an extraordinary entrepreneur whose story was told in a New York magazine article by Mark Jacobson. As adapted into a (somewhat fictionalized) screenplay by Steve Zaillian (“Schindler's List“), Lucas is a loyal driver, bodyguard and coat holder for Bumpy Johnson (who has inspired characters in three other movies, including “The Cotton Club“). He listens carefully to Johnson’s advice, cradles him when he is dying, then takes over and realizes the fatal flaw in the Harlem drug business: The goods come in through the Mafia, after having been stepped on all along the way.

So he flies to Thailand, goes upriver for a face to face with the general in charge of drugs, and is rewarded for this seemingly foolhardy risk with an exclusive contract. The drugs will come to the United States inside the coffins of American casualties, which is apparently based on fact. It’s all arranged by one of his relatives.

In terms of his visible lifestyle, the story of Frank Lucas might as well be the story of J.C. Penney, except that he hands out turkeys instead of pennies. Everyone in his distribution chain is reasonably happy, because the product is high quality, the price is right, and there’s money for everyone. Ironically, an epidemic of overdoses occurs when Lucas’ high-grade stuff is treated by junkies as if it’s the usual weaker street strength. Then Lucas starts practicing what marketing experts call branding: It becomes known that his “Blue Magic” offers twice the potency at half the price, and other suppliers are forced off the streets by the rules of the marketplace, not turf wars.

This is an engrossing story, told smoothly and well, and Russell Crowe’s contribution is enormous (it’s not his fault his wife complains). Looking like a care-worn bulldog, his Richie Roberts studies for a law degree, remains inviolate in his ethical standards and just keeps plugging away, building his case.

The film ends not with a “Scarface“-style shootout, but with Frank and Richie sitting down for a long, intelligent conversation, written by Zaillian to show two smart men who both know the score. As I hinted above: less “The Godfather” than “Wall Street,” although for that matter a movie named “American Gangster” could have been made about Kenneth Lay.