Felice is Jewish and a lesbian, in Berlin in 1943–which means she is walking around with a suspended sentence of death. She takes incredible chances. She works for an underground resistance group, and her daytime job is as the assistant to the editor of a Nazi newspaper (“What would I do without you?” he asks). Her strategy is to hide in plain view; her boldness is a weapon. Then she falls in love with Lilly.

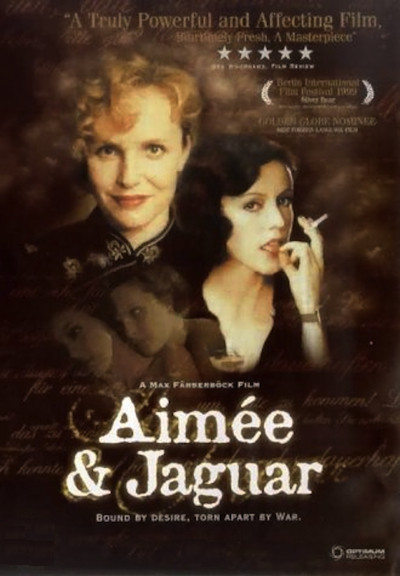

Lilly (Juliane Kohler) is the mother of four. Her husband is away at the front. The first time we see her, she is at a Beethoven concert with a German officer–not her husband. She cheats. He cheats, even with their nanny. It is wartime. One night at a club, Lilly is swept up by Felice (Maria Schrader) and her friends; she’s too naive at first to know they are lesbians, and doesn’t figure out Felice is Jewish until she is finally told. Why would you suspect that of an employee of the Nazis? “Aimee & Jaguar” (Lilly and Felice’s pet names for each other) is based on a true story. Lilly Wust is alive today, at 85, and is the subject of a book that inspired the film. Felice almost certainly died in the concentration camps; her death was hastened because Lilly heedlessly tried to visit her there, calling the wrong kind of attention. War is a time for desperate and risky love affairs, but theirs was so dangerous it was like an act of defiance against the laws, the state, the world, all set against them.

It is pretty clear that Germany is losing the war, that the end is not far away; the bombs rain on Berlin, and through her underground sources, Felice knows even better than her editor of the German defeats. The movie suggests that a few Jews who did escape identification were able to survive in a sort of shadowland. Early in the film, a German woman in a restroom sells food stamps to women she knows (or assumes) are Jewish, and later other Germans know Felice’s secret but do not reveal it. They support a genocidal state, but are unwilling to take personal action. There is even a subtle and delicately written scene suggesting that the editor of the Nazi paper realizes Felice is not what she seems, and chooses not to know.

For Lilly, love with Felice is a revelation. At first she doesn’t even realize her new friend is a lesbian, and when Felice kisses her, she reacts with horror. On reflection, she is not so horrified at all, and soon they are lovers. There is a sex scene in the movie, not graphic in its visual details but startling in its intensity, that is one of the most truthful I have seen. Most lovers in the movies are too in command; the actors fear the embarrassment of lost control. A person having an orgasm can look funny, even ridiculous, to an outsider, which is why you won’t find many movie stars who really want to fake it all that well. When Lilly and Felice make love, there is a trembling, a fear, a loss of control, that colors all the scenes that follow.

Maria Schrader plays Felice with a kind of doomed and reckless bravery. She must know her days are numbered. She cannot get away with her deception forever, and when she is caught, she will not be just any Jew, but one who penetrated to the center of the Nazi establishment–who partied with those who had condemned her to death. She is initially attracted to Lilly as sort of a lark; it might be fun to take this officer’s wife, this mother of four little Aryans and conquer her. Then they are both surprised by love.

There is a moment in the film when it appears that the nightmare is ending. A report spreads of Hitler’s death, after the failed assassination plot by some of his officers. No one knows quite how to respond; Felice is too cautious to reveal her feelings, but among Berliners in general there is the unstated feeling that the war was lost anyway, and might as well end. Then Hitler goes on the radio to declare himself untouched, and for Felice, his voice is a death sentence: she will not get another pass, she senses. “I’m Jewish, Lilly,” she tells her lover. Lilly looks at her in surprise, and then asks, “How can you love me?” It is the crucial moment of the movie.

“Aimee & Jaguar” has some holes in its storytelling that raise questions. How can Lilly’s husband return from the fighting seemingly at will? Was Felice hired by the newspaper without any personal documentation? These questions do not matter. What matters is that at a turning point in her life, Felice is given a chance to escape Germany, and stays. Maybe she didn’t have a choice. This is the kind of story that has to be true; as fiction, it would not be believable.