Chain-smoking and Birkenstock-wearing 55-year-old Dorothea “comes from the Depression,” explains her 15-year-old son Jamie, as though “The Depression” is the planet Jupiter. She presides over a rambling household with an open-door policy. Dorothea has a way of squinting tightly when she listens to people talk: she tries to figure out what’s really going on beneath the surface. Her son wriggles away from that piercing gaze. She throws makeshift dinner parties for friends (and anyone else she happens to meet over the course of her day). She’s a homebody, but not a recluse. She’s somewhat confused by the cultural changes since her own youth (“They know they’re not good, right?” she asks when she hears a song by Black Flag). She’s “from the Depression.” She’s tough. Dorothea is played by Annette Bening in “20th Century Women,” writer/director Mike Mills’ wonderful third feature film, and it’s one of the best performances of the year (and one of Bening’s personal best as well).

Mills is a hell of a writer. That was evident in his second feature, “Beginners,” where Christopher Plummer gave an Oscar-winning performance as a father who came out of the closet at age 75. “Beginners” was about Mills’ father; “20th Century Women” is about his mother. Together the films form bookend narratives of love, tribute and elegy. John Steinbeck wrote East of Eden, in part, for his two sons, to show them what his childhood had been like, what Salinas Valley was like back in the day, what their ancestors were like. It’s a documentary-like approach to a personal history. Mills’ films have a similar quality. They aren’t acts of nostalgia filmed through a golden gauzy filter. They want to communicate something. Similar to “Beginners,” Mills uses archival photographs and voiceover to express the connective tissue as well as the abyss between the present and the past. The future is present too. “20th Century Women” is narrated, for the most part, by Jamie, although all of the other characters contribute. They tell us who they are, where they came from, where they’re going. This approach is like peeking at the last page of a novel.

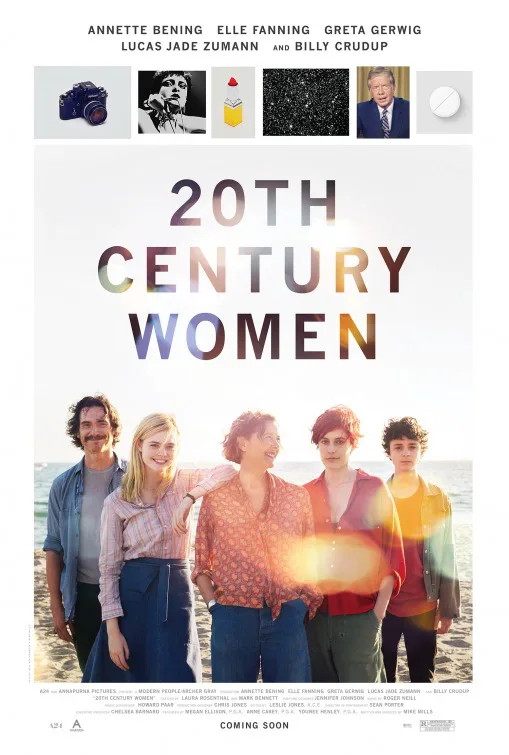

“20th Century Women” takes place in Santa Barbara in 1979. Jimmy Carter looks exhausted on TV. Teenage girls smoke cigarettes and devour Judy Blume’s “Forever.” The new crazes are skateboarding and punk music. Dorothea had her son Jamie (Lucas Jade Zumann) at the age of 40 and has raised him alone. Two tenants rent a couple of rooms in Dorothea’s rambling fixer-upper house: Abbie (Greta Gerwig), a maroon-haired photographer recovering from cervical cancer, and William (Billy Crudup), a mechanic/potter/carpenter who still speaks hippie-speak (“energy,” “earth mothers”), and is tolerant, aimless and helpful. Jamie’s best friend from childhood, a ragingly depressed and promiscuous girl named Julie (Elle Fanning), is so unhappy at home she crawls through Jamie’s window at night to sleep (platonically) with him on his mattress on the floor. Jamie, naturally, is in agonies of horniness about this situation.

In a panicked impulse, Dorothea senses that a single mother might not be “enough” to usher Jamie into this new phase in his life. She asks Abbie and Julie to help Jamie by sharing their lives with him. How this will help is not exactly clear, and Abbie and Julie are confused, but they give it a go. Over the course of the film, Abbie takes Jamie out to punk music clubs and gives Jamie hardcore feminist literature to read. He really takes to it, getting into a fight with a boy at school over “clitoral stimulation” which then leads to one of the funniest exchanges in the film when Jamie explains to Dorothea what the fight was about. (Bening has one of my favorite line readings of the year in that scene: “Okay. Jesus. Yeah.”) Jamie is surrounded by eccentric, complicated women. Their bodies are confusing and erratic: Abbie’s “incompetent” cervix, Julie’s pregnancy scare, Dorothea’s aging process. Jamie wants to understand and wants to be there for them. He tells his mother, “I want to be a good guy, you know?” He means it.

What is so special about Dorothea (and every character in the film) is that they aren’t “quirky” in an annoying, independent film way. They are bizarre and sui generis, as people are in real life. This quality is hard to come by in film. It can’t be faked. It’s in Mills’ script, that’s for sure, but it’s also in his casting. He casts well and then gets out of their way. Everyone inhabits their character like a well-worn sweater. By the end of “20th Century Women,” you really feel like you have gotten to know all of these people. There are so many great scenes, including one of the most awkward and hilarious seduction scenes in recent memory.

During scenes in the house, cinematographer Sean Porter sometimes pushes the camera slowly towards the characters sitting around the kitchen table, or pulls it back, the camera moving towards the doorframe. It’s subtle, almost imperceptible, but it provides a clear sense that “20th Century Women” is an act of memory. The camera seems to be Jamie’s perspective in the future, thinking, “Oh, wait … remember that one conversation in the kitchen? Who was there again? What was said again? Oh, that’s right, that’s right … I remember now.”

The photos, the movie clips, the newsreel clips are all ways that help him, the director, and Jamie, the narrator, to remember. “Beginners” had an inciting dramatic event. “20th Century Women” does not, except for the mildly-contrived request Dorothea makes to Abbie and Julie to share their lives with her son. The film is a portrait of a group of people at a specific moment in time, how they lived, what they fought about, what music they listened to, what they ate and what they cared about. Nothing is irrelevant with that approach. The most pleasurable aspect of “20th Century Women” (and it’s pleasurable throughout) is that it allows itself to be messy. The plot is not bossy, it does not make demands, there are no requirements placed on the characters by an over-planned story. The characters are allowed to breathe. People are weird. People are beautiful. People are annoying and complex. You never ever know what they’re going to do next. You never know what’s going to happen next. Remember that, the film says. It’s important, maybe the most important thing of all.