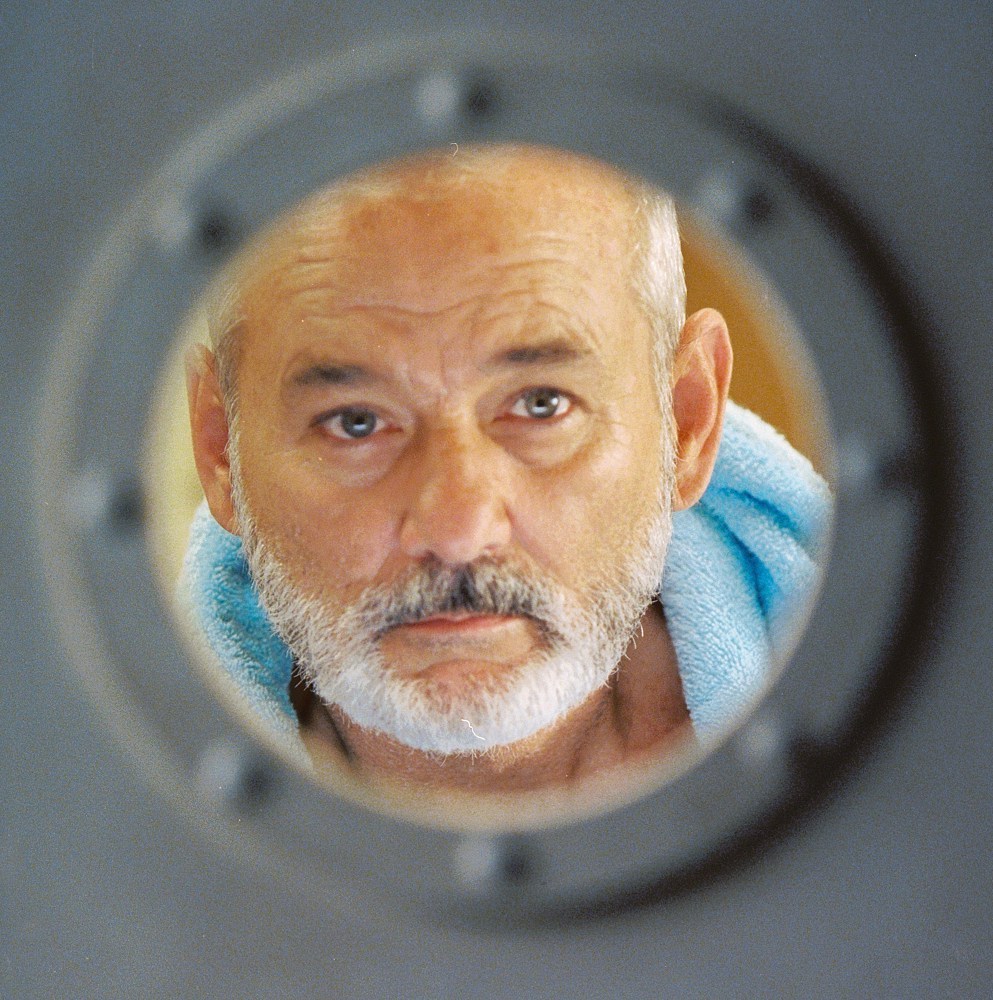

When I tell people that my favorite Wes Anderson movie is “The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou,” they look at me funny. And why wouldn’t they? Cowritten with Noah Baumbach (“Kicking and Screaming,” “The Squid and the Whale“), it’s Anderson’s longest, strangest, most tonally and (perhaps) visually ambitious picture, and it made about eight dollars at the box office and was despised by critics.

I exaggerate, but only slightly. This is, point of fact, Wes Anderson’s biggest-budgeted production, and his biggest disappointment in relation to cost. When it hit theaters in late 2004, few American critics had anything good to say about it. I was in that minority, as was my New York Press colleague Armond White and…not too many others that I know of. At the New York Critics Circle voting meeting that year, I proposed it for awards in a number of categories, including best director and cinematography, knowing that the suggestion would inspire eye-rolls and derisive laughter, because I hoped that maybe somebody in the room would think, “Hey, if he really loves it that much, maybe there’s something to it after all, and I should give it another chance.” I don’t think there were any takers. To love “The Life Aquatic” felt, at the time, a bit insane. Maybe it still does. It’s his least perfect movie, without a doubt. It’s almost certainly too long, and there are sections that drag or feel somehow off or that just flat-out don’t quite work, at least not as they needed to in order to please a wide audience. But it’s wonderful all the same. I cherish its imperfections to the point where they no longer seem like imperfections.

I love how Roger Ebert’s review of “The Life Aquatic” quotes a cutting phrase from his TV review of the film, but in service of what already feels like a revision: “My rational mind informs me that this movie doesn’t work. Yet I hear a subversive whisper: Since it does so many other things, does it have to work, too? Can’t it just exist? ‘Terminal whimsy,’ I called it on the TV show. Yes, but isn’t that better than half-hearted whimsy, or no whimsy at all? Wes Anderson’s ‘The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou” is the damnedest film. I can’t recommend it, but I would not for one second discourage you from seeing it.'”

My already great admiration for the film grew as I dealt with a string of deaths between 2006 and 2009—my wife, my best friend and my stepmother, one after the other.

I watched “The Life Aquatic” a couple of times a year during that period. Each time it helped me a bit more, for reasons I get into in this video essay, as well as in the forthcoming fourth chapter, about the similarly-death-haunted “The Darjeeling Limited.”

Few American directors are as obsessed with the continuing psychic aftershocks of loss as Anderson, as this film, “Darjeeling” and “The Royal Tenenbaums” and “Rushmore” make plain. And yet somehow his movies don’t feel morbid. They take a marvelously balanced attitude, cherishing all the bustle and humor and pettiness and absurdity and other mundane realities that make up daily life in the aftermath of catastrophe, but without minimizing the burden of all that weight. This is is one of the very few movies that I can unhesitatingly say made a tangible, positive difference in my life.

I’ve reprinted a version of the “Life Aquatic” essay that appears in “The Wes Anderson Collection.” It’s quite a bit longer than the version that made print, with more digressions, but considering the subject, that seems somehow fitting.

“I’m going to go on an overnight drunk, and in ten days I’m going to set out to find the shark that ate my friend and destroy it. Anyone who wants to tag along is more than welcome.”

With that declaration, the naturalist/director/pothead hero of The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou drags the crew of his research vessel The Belafonte on a mission to kill the dreaded Jaguar Shark. It sounds like the plot of a sci-fi thriller, or maybe the umpteenth retelling of Moby Dick or Jaws or some other nautical epic. But while Wes Anderson’s fourth film draws on these modes and others, it’s defiantly unique. Like its predecessor The Royal Tenenbaums, but more so, Aquatic anchors its dazzling images and zig-zaggy detours to strong, basic themes: the lived experience of grief; the futility of revenge; the anxiety of entering middle age and wondering if you’ll leave a legacy along with your unfinished business.

Dry comedy segues into romance, farce, violence and deep sorrow. There are lyrical montages, funky action setpieces and shots of obviously stop-motion animated sea creatures with made-up names: sugar crab, golden barracuda, crayon pony fish. Cowritten with Noah Baumbach,The Life Aquatic is patchwork personal expression on a grand scale. It’s as simultaneously old-yet-new-seeming as Zissou’s boat, a refurbished World War II frigate containing a research lab, a movie studio, and spa with a sauna designed by an engineer from the Chinese space program. No wonder it was a critical and commercial disappointment: it’s as immense and weird yet clearly personal as Jacques Tati’s Playtime, Steven Spielberg’s 1941, Martin Scorsese’s New York, New York, and Francis Coppola’s One from the Heart — box-office bombs whose reputations grew over time.

Zissou is the nexus of the film’s style and themes, a marine biologist and documentarian who worries that he’s lost his mojo. He hasn’t had a hit in twenty years. His rival Alistair Hennessey (Jeff Goldblum), has stolen his thunder and is sleeping with his ex-wife, Eleanor (Anjelica Huston), the business brains of Zissou’s operation as well as its moral compass. Zissou is vexed by profit-minded backers and a nosy reporter, Jane-Winslett Richardson (Cate Blanchett) who seems to want to praise and bury him at the same time. And he’s still in mourning for his beloved friend Esteban (Seymour Cassel).

There’s a bright spot: the possibility that a young acolyte turned investor, Air Kentucky pilot Ned Plimpton (Anderson’s regular collaborator Owen Wilson), might be his illegitimate son. Of all Anderson’s charismatic fathers and father figures, Steve is the most complex and contradictory. He’s Jacques Cousteau, Captain Ahab and Andy Hardy rolled into a spliff and smoked by Tommy Chong. His flaky sincerity that undercuts his arrogance and makes him seem, if not lovable, then at least tolerable, and sometimes pitiable. As Zissou, Murray is at once exuberant and depressed, bitter and open-hearted. It might be his most stylized yet human-scaled performance, rivaled only by his work as the hero of Jim Jarmusch’s Broken Flowers, another middle-aged stud who suffers an existential crisis when he learns that he might have a son he didn’t know about.

Steve and Ned’s maybe father-son relationship is thrown off-balance when Steve falls for the pregnant Jane, then loses her to the man-child Ned. This awkward love triangle is awkward but ultimately healing, and it releases prismatic new colors in the characters. It’s like a hall of mirrors that obliterates labels, blurs boundaries and makes everyone resemble everyone else. Ned was raised by a single mom that he recently lost to cancer — the same woman Steve seduced and abandoned decades ago. Jane is a single mother who was knocked up and abandoned by her editor. Steve lost two seeming father figures, Esteban and his mentor Lord Mandrake, to death, and his mate Eleanor to divorce. Like Rushmore‘s Max Fischer and Herman Blume, Steve and Ned seem like brothers as well as father-son, and their competition for Jane has an aspect of sibling rivalry. When Jane reads to her unborn child and Ned listens in, he’s the adult that Jane’s baby will one day become, and she’s the mom that Ned lost.

The Steve-Ned-Jane configuration is a microcosm of the movie’s specialness. The Life Aquatic treats all of its characters — including Willem Dafoe’s insecure and jealous Klaus and Bud Cort’s bond company stooge-turned-hostage — as if they are real people whose dreams and fears matter. This is not how things are done in whimsical movies. Imagine a Peanuts strip in which Schroeder tried to catch a pop fly, got hit on the head, and died in Charlie Brown’s arms while Snoopy wailed inconsolably, and then the next day Charlie Brown went to Lucy’s psychiatry stand to talk about it, suffered through one of her vain and obtuse monologues, then sighed, “Good grief.” That’s The Life Aquatic: a comic strip with characters that cry real tears and bleed real blood, zipping from slapstick to tragedy and back again like Seu George’s fingertips gliding on a fretboard. When Steve meets the young man who might be his son, he’s so stunned that he ambles away from Ned to the other end of the boat and smokes a joint in slow-motion while David Bowie’s “Life on Mars” swells on the soundtrack. When Ned dies in a helicopter accident, his passing is signaled by a subjective rush of flash-cuts, a life-before-his-eyes barrage similar to the one that marked Richie’s suicide attempt in The Royal Tenenbaums; then the movie goes mute, expressing the crew’s shock and sorrow in a silent montage backed by The Zombies’ “The Way I Feel Inside.” All this plus plus a training montage scored to Devo, a stop-motion fight between horny sugar crabs, and a commando raid that feels like a James Bond setpiece directed Frank Tashlin. It would be inconceivable if you weren’t sitting there watching it.

Like Anderson’s second and third features, The Life Aquatic was shot in CinemaScope, a super-wide rectangular format created to envelop the viewer. In the age of home video, ‘Scope is more often used for action movies, science fiction films and historical epics, not comedies. But here, Anderson and cinematographer Robert Yeoman (who shot the director’s previous films) manage to have it both ways. The framing is at once spectacular and intimate, elevating characters to heroic scale in close-ups and taking them down a peg in wide shots that turn them into flyspecks. More often than not, Anderson plants people and objects dead center in the frame, surrounded by acres of negative space, pinning them to their environments like butterflies behind glass. When the camera moves, the shot often starts with one perfectly composed, perfectly balanced, color-coordinated composition and ends with another. It’s as if the film is continually trying to get a handle on these people even as they try to get a handle on themselves.

Among other things, the film is about living life as it happens, appreciating whoever you are and whoever you’re with rather than constantly obsessing about the past and future. As Steve tells Eleanor, speaking words he doesn’t yet recognize as wisdom, “Nobody knows what’s going to happen. And then we film it. That’s the whole concept.” Steve is constantly trying to turn his life into a narrative with a clear direction and satisfying outcome, but his efforts are as forced as the cornball voice-overs in his partly staged “documentaries” and the strained ad-libs he and Ned devise on that jellyfish beach. Steve is a man who likes to be in control of everything even though he can’t control much. His mission to kill the Jaguar Shark is the ultimate act of hubris: he wants nothing less than to track and kill Death and re-assert autonomy over his life. In time he’ll learn this isn’t possible.

Steve’s journey takes him out of narcissism and through the stages of grief, ending in acceptance. At the start of the film, he gets drawn into a first-fight at the Locarno Film Festival when a paparazzo asks a cruel but legitimate question: “Why aren’t you sitting shiva for your friend?” When Steve returns to the festival, he doesn’t attend the premiere of his now-completed documentary, choosing instead to sit outside in solitude. Speaking to his worried financial backers at the start of the story, Zissou deadpans that he’ll catch the shark but let it live, then adds, “Now what about my dynamite?” But the second gut-punch of Ned’s death knocks the rage out of him. Near the end of the story, Zissou, his crewmates, his ex-wife, his patron, and his chief rival pile into a yellow submersible, descend to the ocean floor (bottoming out) and observe the monster through portholes. It’s a meeting rather than a battle, and it seems to restore everyone’s equilibrium, especially Steve’s. They can’t kill death or let it live; all they can do is watch it swim up to the sub, snag a fish and swim away. Steve’s catharsis comes not through dynamite, but tears. “I wonder if it remembers me?” he asks. The sequence is the ghastly climax of Moby Dick re-imagined as a comedy of enlightenment: Ahab finally confronts the beast that maimed him and realizes it was nothing personal.