Albert Maysles, who died last week, was one of the great American filmmakers. His legacy is so immense and multifaceted that I can’t face trying to sum it up. I also knew him personally, as did a lot of documentarians and filmmakers, and held him in equally high regard as an artist and a man.

This post is not meant to substitute for a deep dive into his filmography, nor is it aimed at people who already know a lot about Maysles. It’s more of a grab-bag of impressions gleaned from watching the man’s films and speaking to him on occasion. Think of it as a series of caught moments.

1. Albert Maysles got his start in the 1960s as part of the so-called Direct Cinema movement, which was founded by documentary filmmaker Robert Drew. Drew, who started out as a newsreel cameraman in the Air Force, hated the usual way that nonfiction films had been done up until then. He thought they tried too hard to mimic the rhythms of fictional films and were too concerned with telling a neat story with a beginning, middle and end, and which often included narration, charts, graphs, maps and the like.

Part of the problem, Drew told me, was aesthetic and logistical: the equipment that documentary filmmakers felt they had to use was often unwieldy, and could kill spontanaeity. Ditto the aesthetic they felt compelled to embrace: Hollywood “beautiful,” with excellent lighting and sound, and subjects saying very on-point things without many digressions, with the entire thing aiming to tell you how to feel at every moment.

Drew hated that kind of documentary. He said he had more respect for Fox’s reality series “COPS” than for most contemporary documentary films because “at least they show you situations without constantly telling you what to think.” His great innovation was to devise a lightweight 16mm camera with sound recording equipment attached to it. By changing the equipment, he changed the aesthetic.

When I was writing for New York Press, I profiled Drew, who lived in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. He took me down into his basement and showed me the first prototype of a Direct Cinema 16mm film camera, and let me hold it.

Drew was the leader of Drew Associates, a group of filmmakers who altered

how movies were made. Their ranks included D.A. Pennebaker (Don’t Look

Back, The War Room), Richard Leacock (A Happy Mother’s Day) and Albert

Maysles (Gimme Shelter). They created what’s now known as cinema

verite?or as Drew calls it, “direct cinema.”The first example of

this new type of film was ‘Primary,’ a documentary shot and released in

1960. Filmed in collaboration with cameramen Maysles and Leacock, it was

about John F. Kennedy and Hubert Humphrey facing off during the

Wisconsin Democratic primary.While ‘Primary’ got a theatrical

release in Europe, compared to the typical top-of-the-line Hollywood

picture made during that era, or even a Roger Corman-type exploitation

movie, it wasn’t seen by that many people. But many who did see it were

filmmakers, and they were stunned by what they saw: a documentary with

no title cards, no onscreen host, little narration and almost no music.

They saw a nonfiction film that was more concerned with observing people

in action than in verbally summarizing them. Drew and his collaborators

simply hung out with the candidates and observed them interacting with

voters and the press, or absorbing information from staffers, or eating

lunch, or riding on a bus looking out the window at livestock zipping

by. It was all so simple that it felt revolutionary.Drew’s

esthetic, and the equipment required to create that esthetic, encouraged

the industry to create smaller 16mm and 35mm cameras and indirectly

spurred the invention of Super 8mm, which remained the consumer format

of choice until the mid-80s, when cheap home video came in and replaced

it. That camcorder you used to tape your friend’s wedding exists partly

because Drew and men like Drew believed that everyone should have the

ability to make movies, preferably on a moment’s notice. The unspoken

mantra behind Drew’s process was, “smaller, lighter, faster” a school of

thought that continues to drive not just filmmaking, but every aspect

of media technology.

Maysles, who worked with Drew and considered him a mentor, said that at some point around the end of the 20th century, he and Drew and a lot of other major documentarians rejected analog nostalgia for celluloid, embraced video, and didn’t look back. The newer technology dovetailed with Direct Cinema’s philosophy of caring more about intimacy and immediacy than classical storytelling and slickness.

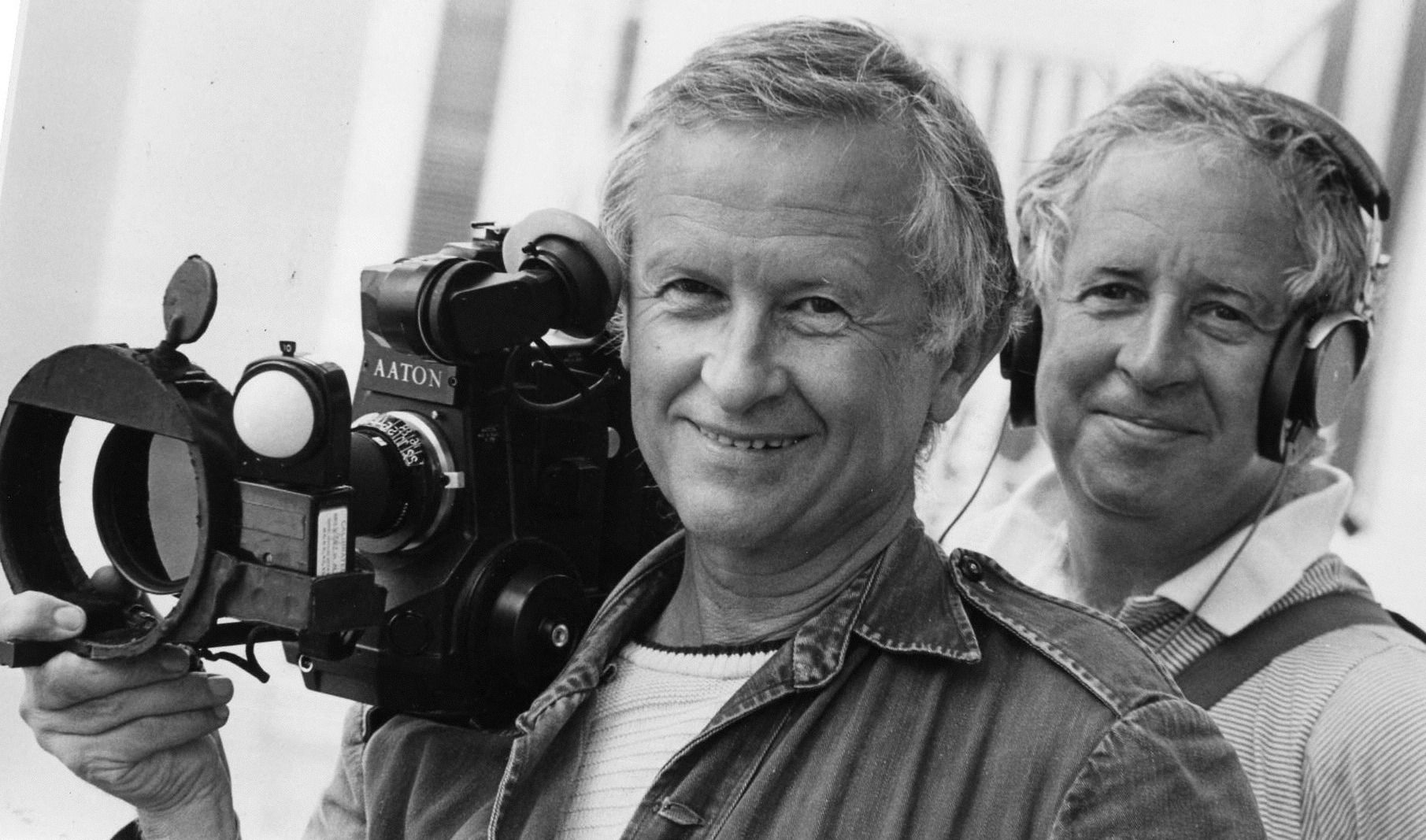

2. Albert Maysles and his brother David were one of the great filmmaking teams in American cinema.

Most of Al’s early work was made as part of this team. Al handled the camera, David handled sound. They were (and perhaps still are) as inseparable in the film buff’s mind as the Coen brothers or the Wachowskis any other tight-knit team of sibling filmmakers.

They did many classic shorts and features together, including “What’s Happening! The Beatles in the USA,” “Meet Marlon Brando,” “Six in Paris” (shot by Jean-Luc Godard, an admirer of the Maysles), “With Love from Truman” (about Truman Capote), “Gimme Shelter,” “The Burks of Georgia,” “Grey Gardens,” “Vladimir Horowitz: The Last Romantic,” and 1990’s “Christo in Paris.” The latter was released posthumously, three years after David’s death of a stroke.

When I visited Albert Maysles in 2002, I asked him about David. He told me, “I miss him terribly. He was a very strong-willed person, with his own ideas of what was good, and I won’t pretend we always got along. In fact we fought a lot, usually about what was the right decision to make for the film. But every time I shoot anything there’s a point where I think, ‘What would David think we should do here?’ or ‘Would David like this?'” Albert Maysles seemed so troubled by the subject of his brother that I didn’t press the issue further.

3. “Gimme Shelter,” an account of the murder at the 1970 Rolling Stones concert at Altamont Speedway, is still the most evocative record of the moment when the utopian dreams of the ’60s, which had been on the decline since the Summer of Love, irrevocably collapsed, giving way to the more cynical ’70s.

It was also the first major American documentary to interrogate the filmmaking process. As such, it’s what contemporary viewers might call “meta.” It has a framing device wherein the Maysles show Rolling Stones frontman Mick Jagger footage of the escalating violence at the concert (which used increasingly drunk and belligerent Hell’s Angels as security) and the scuffle that ended with a concertgoer getting stabbed. The Maysles keep running the footage back on a film editing deck, going through it frame-by-frame as it it were the Zapruder film, isolating the flash of a knife blade and the shocked expressions on onlooker’s faces.

A lot of people, including New Yorker critic Pauline Kael, complained that the Maysles seemed to be pinning blame for the conditions that led to the killing on the Stones and the concert’s promoters. But I’ve always detected a feeling of culpability in the film. The framing device is key. It is self-indicting. It’s an autopsy of an experience.

The editing room scenes of “Gimme Shelter” are very much in tune with the Maysles’ philosophy. They are showing you what happened, and communicating what they thought it meant, through observation and arrangement of material rather than by coming right out and saying, “Think this, believe that.” If the Maysles didn’t want to accept some measure of guilt or responsibility for what happened at Altamont (which was created mainly so that it could be filmed), I doubt they would have kept calling viewers’ attention to the fact that they were watching an accidental snuff film.

As the duo’s career went on, they acknowledged their presence in their stories regularly and openly, but subtly, and only when a moment left them no choice. In “Grey Gardens,” the peak of their ’70s output, the Maysles’ brothers’ presence at the home of a rich and eccentric mother and daughter, both named Edith Beale, is announced early in a newspaper clipping, and acknowledged throughout the film. When the sisters address Albert or David by name, or when Albert’s camera pans to catch himself in a mirror or David over in a corner operating sound equipment, we become more keenly aware that we’re not really flies on the wall, that this whole thing is constructed for our interpretation and pleasure. Sometimes the women talk to “David” or “Albert” and you hear them answering. The funniest of these moments finds big Edith contemplating doing a soft-shoe routine and asking the filmmakers, “Do you think I’m going to look funny dancing?” “No!” they respond, in unison.

I wonder if this sort of thing was an outgrowth of, or even a response to, criticisms that they were trying to eat their cake and have it, too, in “Gimme Shelter”? Or if they were refining whatever sort of auto-criticism they were attempting in “Gimme Shelter,” but failing to put across to viewers such as Kael? In “Grey Gardens,” it’s almost as if Albert and David Maysles are doing something similar but taking no chances this time. It’s like they’re saying, “We and our subjects all know that this is a movie, and that the people passing before our lens might not behave in precisely the same way without filmmakers around—and the audience knows this, too. So why not just lay our cards on the table?”

As the New Yorker‘s Richard Brody wrote, “For the Maysleses, the performer and the audience are as inseparable as the participants in a documentary and the documentarians. That’s why, in their easy-going, humanistic, and graceful way, the Maysleses were among the exemplary modernists of the era, including themselves in the onscreen action and making their presence felt, physically as well as ethically, as audaciously as any avant-gardism.”

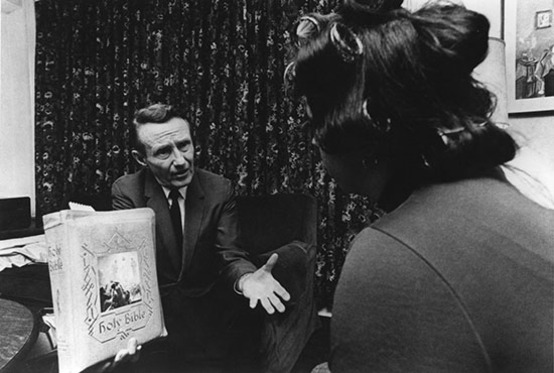

4. The Maysles’ brothers’ 1968 film “Salesman,” about door-to-door Bible salesmen, is one of the great statements on America’s can-do culture of capitalism, and how it tends to become a psychological cage that makes people feel like failures.

One the film’s most devastating quotes is “If a man’s not a success, he’s got no one to blame but himself.” This rings hollow, not because the Maysles went into the project looking to puncture capitalist credos, but because you can’t follow middle-aged guys around suburban neighborhoods, watching them mostly fail to sell pricey Bibles to people who don’t want them or can’t afford them, and come away thinking the American Dream is doing fine, thanks.

As I wrote in a 2007 piece for my first blog, The House Next Door:

‘The movie is not just a social and political landmark, but a technical

and aesthetic one as well. Shot with compact sync-sound cameras devised

by pioneering nonfiction filmmaker Robert Drew, the father of so-called

cinema verite, ‘Salesman”s

embellishment of the genre’s developing vocabulary pushed documentaries

further away from the goal of simply recording life…There’s surprisingly little naivete in ‘Salesman’,

and not a rube in sight. Customers and vendors have no evident

illusions about what’s really being bought and sold: a false sense of

spiritual/social confidence, framed in materialist language that’s

blasphemous by definition. In ‘Salesman,’

door-to-door Bible salesmen are doing God’s work, all right, but it’s

not the God of the Old or New Testament. It’s the God of money as

enshrined in America’s true gospel—the assurance that ours is an

egalitarian, capitalist meritocracy, a level playing field where the

best man wins. The film’s frank skepticism toward this cherished myth

makes it one of American pop culture’s greatest statements of doubt, on

par with its spiritual forerunner, Arthur Miller’s ‘Death of a Salesman,’ and its descendant, David Mamet’s ‘Glengarry Glen Ross’ (the film version of which contains a scene quite similar to one in ‘Salesman,’ in which a representative of the head office parachutes into a sales meeting to terrorize low earners)…

As Maysles told me in a 2007 Q&A at the Museum of the Moving Image in Queens, he brought some of his own personal experience to the subject.

I sold Fuller brushes in high school; and when I got out of college, for as long as I could stand it—which was two or three weeks—I sold Encyclopedia Americana. And my brother sold Avon products. So we knew that there was a great potential in telling something about America. And we sent out somebody to research the kinds of stuff that was being sold door-to-door.

And in that research, which took several months, the researcher found that there was a company in Chicago actually selling the Bible, but as an item with a beautiful leather binding and lots of color photographs. And somehow: The salesman—who represents the guy who was a rugged individualist, because when he knocks on that door it’s all up to him as to whether he’s going to succeed or fail; and the Bible—being so much an item in our culture, but interestingly enough, sold as a product, right; and then of course, the woman who’s going to be the additional subject of the film—the housewife…You had all the makings of something that would tell us a lot about America. And in fact, when the film came out, Norman Mailer said something to the effect that it’s one of the few films that tells so much about America.

5. Albert Maysles continued to be an ambassador for Direct Cinema throughout his long life, but he wasn’t a stylistic absolutist.

Like his mentor Robert Drew, he believed that documentary filmmakers should capture incidents and personalities, and an overall sense of what it’s like to exist somewhere, and not worry so much about shaping the narrative to prove a certain point. He believed in documentary film as an accumulation of moments. This came through very strongly. In his 1976 review of Albert and David Maysles’ classic documentary “Grey Gardens,” Roger Ebert ended by listing his favorite moments: “Edie feeding the raccoons a loaf of Wonder Bread. Edith placidly observing that a cat is defecating behind her portrait. Edie, nearsighted, standing on a scales and reading her weight with binoculars. Edith confessing that she can’t turn around just at the moment because her bathing suit has no back. The two women at night, alone in their room, the crumbling mansion extending around them, listening to old songs and replaying old memories.”

This

is not the default mode in nonfiction cinema right now.

Documentaries increasingly lean on devices gleaned from fiction

filmmaking: bouncy montages often scored with “ironic” pop; narration, and dialogue used in voice-over as what I like to call “stealth narration”; graphics, animation, and handsomely photographed re-enactments; storytelling devices borrowed from genre films, such as the heist

thriller or the murder mystery. This tendency is a fairly recent (maybe post-’90s) development. In contrast, Albert Maysles and other Direct Cinema

filmmakers preferred to work in a more stripped down mode, one that created a gentle collage of lived experience.

As I wrote of ‘Salesman’, “More than any filmmakers working in the genre up till then, the Maysles brothers and [editor Charlotte] Zwerin showed that it was possible, even desirable, to interpret and report simultaneously—and that the result could bring nonfiction filmmaking closer to social criticism than it had ever gotten before.”

He clung to the idea that he and other Direct Cinema filmmakers were more observers than “directors” in their projects. In fact, Robert Drew refused to take a director credit on his early films because he thought it sent the signal that the material had been shaped or staged, rather than gathered and then arranged.

a distinction between what [David and I] do, and what documentary filmmakers

normally do, and what journalists do. And that is, we get very, very,

very close to what’s actually going on. There’s no narration. There’s

no host. There’s no music that is added to it to give it some sort of a

punch.”

Still, Maysles was upfront in admitting that the arrangement of

material—i.e. editing—was where much of the storytelling happened. You could shape footage to guide viewers

towards particular inferences as long as you weren’t obvious about it. He was OK with compressing or rearranging things here and there, as long as it didn’t grossly distort the essence of the original, unedited footage.

During our discussion at the museum I pointed out two instances in “Salesman” where the film created what amounted to little montages, or otherwise created stylized impressions of moments rather than actual moments. He laughed at being caught, and smiled impishly. “I guess

people are entitled to break their own rules,” he said.

6. Albert Maysles believed the perfect was the enemy of the good, and his work embraced this idea. He was almost perversely proud of the fact that his films, solo or with his brother David, were rough around the edges, that sometimes they missed moments, and sometimes the picture or sound were a little rough, or flat-out bad for a few seconds here or there. It was part of the aesthetic.

He had great instincts as a cameraman–watch his visuals closely, from his early work through a late-period piece like “LaLee’s Kin,” for which he won a Sundance Film Festival cinematography award—and you see a man with such an uncanny sense of where to be, and when, that you’d think he had the ability to read minds. But he never lost much sleep over whether things looked beautiful, or even pretty.

“If

you’re concerned with production value, you’re part of the Hollywood

mindset, no matter how you try to justify it. Hollywood

has always been concerned with production value, to a degree that drives

out other considerations,” he told me, speaking of Robert Drew as well as his own work. “These things are less important than the

content of a movie, and in nonfiction they’re less than irrelevant.”

He elaborated on this in our 2007 talk:

“One of the most brilliant documentary filmmakers is Jonas Mekas. And his stuff—he can’t hold the camera steady. He’s out of focus most of the time. But, my God, what poetry! What a touch with life! What a connection you make with what’s going on! Of course, ideally, you like to have somebody with the professional capabilities of holding the camera steady, and composing the shot, all that stuff. But without the psychology that goes along with the poetry…

Well, Orson Welles put it very well when he said that the eye of the cameraman must be—the eye behind the lens—eye of a poet. And [Robert] Capa, the great still photographer, when asked to give advice to a new photographer, he said, “Get close. Get close.” And I think those are two elements that are so very important, that are oftentimes neglected.”

7. Albert Maysles believed documentary filmmakers had a duty to show their subjects behaving in routine, ordinary ways, and being happy, even when the subject matter was basically grim. “I like to show people functioning in fairly normal ways,” he told me, when I interviewed him in 2002:

“It seems like you’re always having to look at families

killing one another. It’s like people are following Tolstoy’s misguided

statement that all happy families are alike in their own way, but every unhappy

family is different. That makes people conclude, ‘Well, why bother with the

happy ones?'”

8. Albert Maysles was a committed, enthusiastic mentor to younger filmmakers. Talk to almost any documentary filmmaker of the last 40 years who’s made work of any note, and there’s an excellent chance they studied or worked with Albert Maysles. Barbara Kopple, Joe Berlinger, the late Bruce Sinofsky and many other filmmakers got their starts, or a huge boost, through Maysles Films.

Al was also incredibly generous about sharing directorial credit with people whose contributions in specific areas of a given film—such as camerawork or editing—helped give the work its personality or its point. “Grey Gardens,” for instance, gives co-director credit to Ellen Hovde and Muffie Meyer, who studied and worked with the Maysles and went on to form Middlemarch Films, and editor Susan Froemke, who nearly 30 years later would co-direct “LaLee’s Kin: The Legacy of Cotton.” The latter was shot by none other than Albert Maysles, and it won him the first Sundance Film Festival cinematography prize ever awarded to a documentary.

Albert Maysles he didn’t believe that a person had to have attended film school to be a good filmmaker. In fact, the company went out of its way to nurture people who had distinctive world views or fascinating stories but had never gotten anywhere near a film set before—particularly women and filmmakers of color. As Susan Froemke, who started at Maysles Films as a temp secretary, told me in 2002: “The Maysles never wanted to hire anybody who went to

film school. They wanted people who were interested in people, and in everyday

life.”

Al was so generous that sometimes it created problems for the people he worked with.

In 2008, I got the bright idea of pitching Al on doing a documentary about the history of the Direct Cinema filmmakers, including him and his brother, Robert Drew, Richard Leacock, D.A. Pennebaker and Frederick Wiseman (whom Al never considered a true Direct Cinema filmmaker; they always had issues with each other, apparently). I told him my idea at a party and he got excited and asked me to come up to his new headquarters in Harlem to discuss it in detail. I did, but within a few minutes he said, with his customary sweetness, “This sounds like a wonderful idea for a movie, but I don’t want to participate in it because I’m doing my own autobiographical film. I don’t want to scoop myself, I guess you’d say.”

But he said that since I’d come all the way up to Harlem from Brooklyn, I should stay and talk a bit, and maybe tell him some of my other ideas. “Maybe I can help out,” he said.

I told him about a good one—a documentary series idea I’d developed with my then-girlfriend, a blogger, about a cemetery—and his eyes lit up. “Tell you what,” he said, “If you can get permission from the cemetery to shoot there, and if you can get the equipment and the crew lined up, I’ll be your DP. And I won’t charge you anything! I just want to be a part of it.”

I felt lightheaded. Albert Maysles! Albert Maysles wanted to shoot my documentary! I couldn’t believe it.

I ran around taking meetings at production companies and TV channels, using his involvement as a way to convince people that this thing was going to be amazing. Then I’d email him or leave phone messages about my progress. This went on for a few weeks. Al never got back to me. After a while I started to get worried.

Finally I called one of his colleagues at Maysles Films. She said, politely but with evident weariness, “I hate to have to tell you this, but Al is doing so many different things right now that the odds of him actually shooting your documentary for you are not good. I think you should find somebody else, honestly.”

I asked, “Do you think he was just humoring me?”

She said, “Oh, no—I think if Al said he thought it was a good idea, then he meant it, and you should still try to to do it. But you’ve got to understand, unfortunately, part of working with Al is having conversations like this one. He’s so enthusiastic about other people’s projects, and he loves younger people so much, that every good idea he hears about, he tells the the filmmaker he wants to work on it. And he means it! But if he helped all the people he wanted to help, he’d never get any of his own work done. The problem is, he wants to be a part of everything.”

As problems go, that’s not a bad one to have.