Samuel Z. Arkoff, who in some ways invented modern Hollywood, died Sunday of natural causes in a Burbank hospital. The co-founder of American-International Pictures and the godfather of the beach party and teenage werewolf movies was 83.

When Arkoff and partner James H. Nicholson founded AIP in 1954, the major Hollywood studios were little interested in movies aimed at teenagers, or in the summer releasing season. AIP had surprising success with low-budget youth pictures, and took advantage of less competition in the summer to open double-features with titles like “Muscle Beach Party” and “Invasion of the Saucer Men.”

In June 1975, eyeing a situation where AIP and other small indies controlled the summer, Universal released Steven Spielberg’s “Jaws.” Its enormous success convinced the majors that there was gold to be mined in the summertime, and today the summer months dominate the box office. Ironically, the increased competition made it hard for AIP to survive; Nicholson left the company in 1972, and in 1979 Arkoff sold his shares and became an independent producer. He made his last film in 1985, but his legacy continues. What are the recent films “Godzilla,” “Independence Day,” “Armageddon” and “The Mummy Returns” but Arkoff concepts with bigger budgets and better special effects?

It was said that Sam Arkoff produced more films by Hollywood’s best directors and brightest stars than anyone else–and did it the hard way, before they were the best or the brightest. AIP films were directed by Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Brian de Palma and Peter Bogdanovich, and featured early performances by such unknowns as Jack Nicholson, Robert De Niro, Charles Bronson, Barbara Hershey, Nick Nolte and Peter Fonda –as well as making teen immortals out of Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello.

Producer-director Roger Corman became AIP’s favorite in-house moviemaker, making dozens of movies and serving as executive producer for many more. He was praised by young filmmakers for giving them jobs, and cursed for the tiny budgets he allowed them. “Roger was born with cheap genes,” Arkoff beamed, remembering an early Corman western named “Five Guns West,” where Corman decided to save on the salaries of extras by “purchasing stock footage of a legion of Indians on the warpath, and splicing them around closeups of the few actors actually hired for the picture.”

In his 1992 autobiography, Flying Through Hollywood by the Seat of my Pants, Arkoff recalled that the AIP formula was straightforward. First they came up with the title. Then they came up with the poster. If both looked good, they made the movie.

Arkoff’s first film was “The Beast with a Million Eyes,” in 1955. His films were rarely masterpieces, but they sounded like fun, and offered straightforward entertainment values. Even the titles made you smile: “”Ghost in the Invisible Bikini,” “Invasion of the Saucer Men,” “Beach Blanket Bingo,” “I Was a Teenage Werewolf,” “The Astounding She-Monster,” and “The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent.”

Arkoff was a smart, jovial man who never took his movies too seriously. In the 1970s and early 1980s, one of the highlights of the Cannes Film Festival was a festive luncheon he and his wife, Hilda, threw for North American and British film critics at the ultra-expensive Eden Roc Restaurant of the Hotel du Cap d’Antibes, on the coast outside of town.

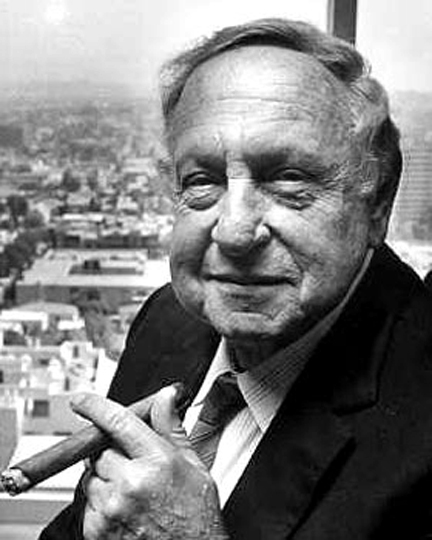

Unlike most events sponsored by Hollywood studios, Arkoff’s featured no press releases, no publicity handouts, no interview opportunities and only one speech. Arkoff, holding his trademark foot-long cigar, would stand up and say, “No business is discussed at this luncheon. The less said about some of my pictures the better. We’re here to have a good time. Eat, drink and enjoy yourselves.” Then he would sit down again.

Critics jostled to get a seat within earshot of Arkoff, whose stories of low-budget movies and high-maintenance moviemakers became legend. One of his favorite stories, later repeated in the autobiography, involved working with the neurotic Hungarian actor Peter Lorre on “The Raven” (1963).

Lorre had the title role, but “sometimes found it hard to keep to the script while dressed like an oversize black bird with four-foot-long wings.” So Lorre ad-libbed. He had a scene where Vincent Price told him his wife’s body was buried in a crypt beneath the house. “Having seen the other Poe pictures, in which the coffin was always buried in a crypt beneath the house, Peter exclaimed, ‘Where else?'”

After selling his stake in AIP, Arkoff became an independent producer, and threw one last luncheon in 1982 at the Hotel du Cap. It was after the screening of his new movie “Q,” about a prehistoric winged serpent that nests at the top of the Chrysler Building and swoops down to pick innocent victims off the streets of Manhattan.

Sam and Hilda stood by the door as always to greet their guests. One of the first was the critic Rex Reed.

“Sam!” said Reed. “What a surprise! Right in the middle of all that dreck, a magnificent Method performance by Michael Moriarty!”

Arkoff beamed with pride. “The dreck was my idea,” he said.