Bill Murray dribbled into the hotel suite and sank the basketball in a chair in the corner. He was wearing your average after-school jock’s uniform of jeans, a T-shirt, and designer running shoes, and he said he needed a shave. He disappeared into the bathroom and then stuck his face out again, covered with lather, and asked, “How do you plan to explain your one-star review of ‘Scrooged‘?”

“I was hoping it wouldn’t come up,” I said.

“It wasn’t that bad,” Murray said. “It had some good stuff in it. Watch it on video and you’ll see.”

“It just didn’t work for me,” I said.

“I thought maybe you had some inside information, you know, about an unhappy set or something,” he said.

“No,” I said, “it just didn’t seem that funny. Did you have some disagreements with the director?”

“Only a few,” he said. “Every single minute of the day. That could have been a really, really great movie. The script was so good. There’s maybe one take in the final cut movie that is mine. We made it so fast, it was like doing a movie live. He kept telling me to do things louder, louder, louder. I think he was deaf.”

That was then, this is now. Murray has a new summer movie opening next week, named “Quick Change,” and he likes it a lot better than “Scrooged.” What worries him a little, though, is that in a summer dominated by high-tech exercises in violence and action, a comedy might not be able to hold its own.

“This movie doesn’t have any violence in it,” he said. “Six months ago that didn’t bother me at all, and it really doesn’t bother me now either, but people are saying things like, This is a gentle movie. I don’t think it’s gentle at all. I think it’s weird and funny. I think it’s as strange as anything. It’s about New York, and it’s weird, but it isn’t violent.

“There’s an audience that talks to the the screen, a screaming audience, that likes the violence, and there’s a bonding that goes on in that group. There’s a moment they’ve got to have, where they get to watch something horrible happen, and they get to enjoy it, without actually having to do it, or be a victim to it. I’ve seen that coming for a few years. I remember the first time I saw a violent movie that was supposed to be a comedy. There was a scene where somebody just got five 9mm slugs in their chest, and they sort of slid down a mirror, and there was this blood on the mirror, and I thought, wait a second, this isn’t comedy. This is something different.

“Or look at some of the movies that did well first time out, like “Die Hard,” “48 Hrs.” or “RoboCop.” They were all kind of funny, even though there was violence in them. Although I haven’t seen any of the sequels yet, I can tell they’re a lot more violent than the originals.”

He thought for a moment, drumming his fingers on the table. “Or maybe it’s just the sequel business itself,” he said. “I made a sequel [“Ghostbusters Two”], and it’s hard, it’s really hard to make a sequel, no matter how sincere you are, how much you want to try. Somehow the directors take over from the writers and the comedians, and the thing ends up being a lot more action than comedy. Action is a lot easier to direct than comedy.”

It’s also easier to advertise. The TV ads give away some of the good parts, like Bruce Willis jumping onto the wing of a plane, or Arnold Schwarzenegger’s face splitting up into slices. It’s hard to sell a comedy that way, since comedies depend more on situations and characters than on single sensational moments. That’s why Murray would be happier if the fate of a movie wasn’t determined so quickly these days, by the box office box score.

“It used to be,” he said, “that if a movie opened up and did a couple of million on its opening weekend, that was a big deal. It’s not like that anymore. They do these big TV buys now. They spend so much money, it’s really scary. We’re going to spend $3 million on Monday. It’s like an army invasion. And when the movies open, all the papers print charts showing which movie grossed the most that weekend. I don’t know why, because in theory only a couple of studios are going to profit from releasing that kind of information. And I don’t know why they print it — if they think it’s news, or they think it makes people interested in movies.”

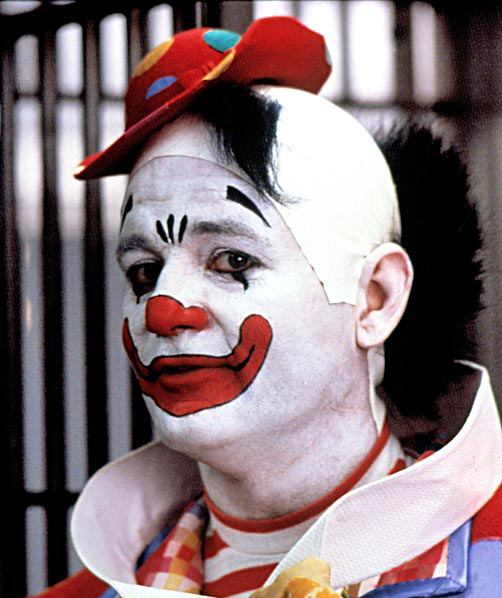

Bill Murray’s own movie will be that kind of news a week from now. In a summer when the studios have laid claim to weekends as if they were gangs defining their turf, Warner Brothers hopes it has the biggest summer comedy. “Quick Change,” stars Murray as a bank robber who disguises himself as a clown and stages a complicated heist, only to experience the most extraordinary troubles in getting to the airport. Geena Davis and Randy Quaid co-star as his partners in crime, and along the way they meet a gallery of character actors in weird supporting roles.

The movie basically split into two parts; (1) The opening bank robbery, in which the New York police become thoroughly confused over who is a robber and who is a hostage, and (2) the attempts by the three robbers to get to Kennedy and board their getaway flight to Fiji. Along the way they meet such characters as an anal retentive bus driver (Philip Bosco) who believes in running a tight bus. There’s also a run-in with some Mafia types, and a wild ride with a crazed cab driver.

The movie’s opening scene discovers Murray, dressed as a Bozo lookalike, riding to work on the subway. Inside the bank, he seems to have a plan firmly in mind, even though he does what he can to make the guards — and the police who quickly surround the block — think he’s a loony. His plan involves a series of disguises, but what I wanted to know was, is a major star taking a chance when he plays all of his opening scenes in clown makeup?

“You do kind of worry,” Murray said, “because you wonder if they’re going to know who you are. You could be so disguised they can’t recognize you. We tried to let the face come through, so I could use my facial expressions. We didn’t want to make it such a mask that I couldn’t react.”

Murray’s face is recognizable, sort of, beneath the greasepaint, but what comes through more obviously is his manner: The laconic, wise-cracking character with the ironic asides and one-liners. That kind of dialog has been a Murray trademark right from the start, in the early 1970s, when he and John Belushi were regulars in the same Second City company. Belushi was always the more physical comedian, and perhaps that helped Murray develop his own persona, of the detached observer who stands in the midst of chaos and maintains his wry point of view.

“The reason so many Second City people have been successful is really fairly simple,” Murray said. “At the heart of it is the idea that if you make the other actors look good, you’ll look good. It works sort of like the idea of life after death. If you live an exemplary life, trying to make someone else look good, you’ll look good too. It’s true. It really does work. It braces you up, when you’re out there with that fear of death, which is really the difference between the Second City actors and the others.

“If you go to actors’ class, you don’t really die, because there’s never really an audience. But if you work for Second City, there’s an audience, and you die in the improv set five times out of nine. So, once you get over your fear of dying, nothing else ever really scares you. And Saturday Night Live was as tough as Second City. Once you get through those, making movies is a joke.

“On a movie they’ll say, all right, we’re only going to have three minutes to get this coat off and get you in the other shirt. And I just start laughing. Three minutes? In three minutes I can take off a shirt, put on a wig, a hat, a fat stomach, an enormous raincoat, galoshes, soak my head, take a shower, and be covered with soap and walk out and talk in another language. It’s nothing!”

He grinned. “People don’t know how hard those jobs were. The National Lampoon show that we did on Broadway was hard too. It was like crowd control theater. It was a brawl every single night, and they were going to take the stage, if you didn’t. It was really an ugly audience. It’s what biker bars are all about. So those three jobs really prepare you. And then, since SNL always had a guest host, there was the tradition of service, of trying to cover for this poor sap, whoever he was. Between dress rehearsal and airtime, they’d be so terrified, they’d be almost weeping in the dressing room. It was a zoo, that show. We’d have the Chinese acrobats of Taiwan, we’d have Jim Nabors, we’d have dog acts, singers, fire-breathers, Argentinian gauchos, there was everything.”

One of the sad things about Belushi’s death, I said, was that ever since then, people have eulogized that period instead of enjoying it. They forget how much fun SNL was.

“People deny they lived in the 1960s,” Murray said. “Did you ever see that Newsweek piece? That big 1960s piece where people said, This is what I was in the 1960s, and I hate myself for it? I hated what I was. I was disgusting. I was wild and really horrible. How really sad. And looking back at SNL, people like to say we were all into heavy drugs and stuff. Well, yeah, anybody who wants to work a 125 hour week could come around and see how well you could do it on drugs. The only drugs involved used were the kind required to keep you in one place for 12 hours at a time, so you’d work.”

After the Second City and SNL days, Murray became a movie star almost overnight, with a couple of low-budget but funny quickies named “Meatballs” (1979) and “Stripes” (1981). He did a famous job of scene-stealing in “Tootsie” (1982), in an unbilled performance as Dustin Hoffman’s roommate. And he starred in “Ghostbusters” (1984), still the best-selling movie comedy of all time.

But in the six years since “Ghostbusters,” Murray’s career has drifted from the sincere but unsuccessful drama “The Razor's Edge” to the unfunny “Scrooged” to the less funny “Ghostbusters Two”. His funniest work during the period was a guest-starring role as a dental patient in “Little Shop of Horrors.”

Why didn’t he make more pictures after the original “Ghostbusters?”

“Well, basically I thought that ‘Ghostbusters‘ was the biggest thing that would ever happen to me. It was such a big phenomenon that I felt slightly radioactive. So I just moved away for awhile. I lived in Europe for six months or so, and I was supposed to do a movie when I came back, and when I came back, and I saw the script that I was supposed to do, I didn’t want to do it. And that put me a whole season behind, and then I went through a kind of funny thing. There are actual moviemaking seasons, you know, and the three weeks before every seasons I would get 20 phone calls a day from people wanting to do a movie, and there would be this incredible amount of pressure. On Friday I’d get like 30 phone calls, and then on Monday no one would call, and I’d look in the paper, and someone else was doing the movie because I didn’t say yes.”

So you’re back on schedule now?

“I don’t ever want to take that much time off again. I don’t want to be somebody with 25 movies in development, because then there’s always 24 people who hate you. It’s good to just keep working. I should have kept writing all that time, because when you take time off, it takes you all that much more time to get back up to speed.”

He got up and went over to the sideboard and opened a beer.

“One of my gripes about movies,” he said, “is that people take them so seriously, and the money making aspects are so brutal. I’ve been lucky, I’ve had movies that made a lot of money, so I don’t feel like I have to kill every time out. I don’t want that pressure. I don’t need it. It’s not right. Look at Warren Beatty, the guy’s having a nervous breakdown. I think. he’s really doing great, but the opening weekend “Dick Tracy” only made $21 million dollars, and so what did he do? He was on every television show including the Home Shoppers Network for the next 72 hours, hyping the box office. And this was with a success .”