“The Loving Story” premieres on Valentine’s Day, February 14, at 9 p.m. on HBO (check local listings), and is available via HBO On Demand and HBO Go thereafter.

“The Loving Story” is as modest and taciturn as its subject, an interracial couple who, in 1958 rural Central Point, Virginia, just wanted to be left alone. For the most part, they were, and that was the problem as much as it was their fervent wish. When the local sheriff busted into their bedroom at 4 am and hauled them off to jail for violating the Racial Integrity Act, there was no national audience, in contrast to the fire hosings, bombings and other acts of racist terror that couldn’t help but make the evening news at the time. The whole world was not watching. It’s hard to fathom why after seeing the luminous 16mm footage uncovered in “The Loving Story.” Documenting many pivotal moments in the case, it adds a dash of something rarely seen in the grand narrative of the American Civil Rights struggle: romance.

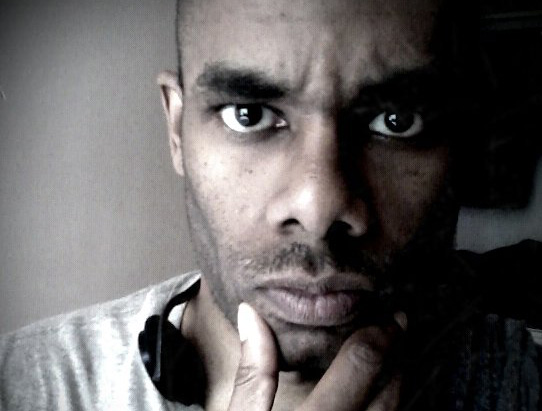

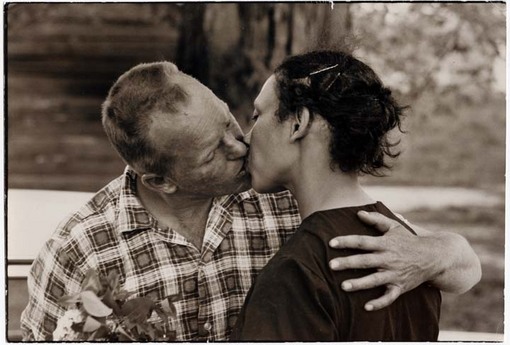

In the footage and iconic photographs, the Lovings appear to be deeply in love. Richard is a silent, barrel-chested Ed Harris lookalike; Mildred is shy and beautiful, the essence of poised intelligence. How could a story this simple and universal, with two photogenic romantic leads captured in a Life magazine feature, get lost in the Civil Rights shuffle?

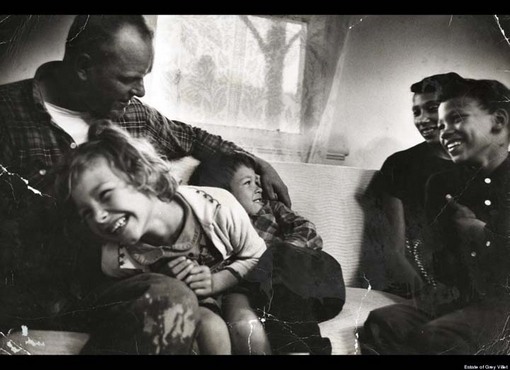

The Loving case eventually went all the way to the Supreme Court, and all along the way, the couple insisted upon discretion and privacy. Only a small documentary crew — filmmaker Hope Ryden and cinematographer Abbot Mills — gained access to their home, but they made the most of it. The photography is as discreet but watchful as Mildred herself. When she, well, lovingly buckles her little daughter’s suede shoe as they prepare for an outing, the camera isolates the mother’s slender brown arm steadying her child’s pale leg. In the film’s context, as assembled by producer-director Nancy Buirski, moments like this one simply cry out, “Why on earth would a decent person want to disrupt this beautiful life?”

We know why, and Buirski knows we know, so she eschews narration for montage and thoughtfully inserted testimonials from those who were there. Almost matching Mildred’s eloquence are Bernard Cohen and Philip Hirschkop, the lawyers who, barely out of law school in the early ’60’s, took up her and her husband’s case. We see the babyfaced attorneys brainstorming in their office with the excitement of rookies at bat for the World Series. They go through the steps that will eventually put the case before the Supreme Court while the Lovings pretend to obey the terms of their Virginia court sentence. They were banished from Virginia in lieu of one-year prison sentences, but they snuck back into the state at every opportunity. They simply could not live for too long without their extended families and friends in tiny Central Point.

As represented in Grey Villet’s photographs of Richard hanging out with his buddies, an interracial band of drag racers, mechanics and musicians, and of the Lovings doting on each other, Central Point seems an edenic refuge from the race madness of the times. “There’s just a few people in this community,” Richard says. “There’s a few white and a few colored, and as we grew up and they grew up, we all helped one another. It was all mixed together from the start, so it just kept going that way.”

There are lots of unanswered or half-answered questions, such as why, if, as Richard insists, there were a lot of known interracial couples in Central Point, did the sheriff single them out? Richard shrugs. “Somebody didn’t like us… somebody talked.” How did such a tolerant and cooperative enclave get stuck with such a hateful county sheriff as R. Garnett Brooks (whose deputy even implies that he was an unreasonable jerk)? If the Lovings (or at least Mildred, who says as much) were unaware of the state’s miscegenation laws, why did they choose to marry in Washington D.C.?

“The Loving Story” leaves a lot of room for these mysteries to reverberate in the viewer’s mind, in stretches of silence and music. In this atmosphere, I found myself mentally casting the inevitable Hollywood (or HBO) film on the Lovings — and not just the leads. The story’s elemental, salt-of-the-earth poetry could work wonders in the hands of such purveyors of troubled cinematic Americana as David Gordon Green, Carl Franklin, David Lynch and Jeff Nichols.

Nine years would pass before the Lovings get a hearing with the U.S. Supreme Court. In the interim, there are trips into Virginia that resemble spy missions (one hazy re-enactment shows Mildred climbing out of the trunk of their car) and dismal times languishing in the D.C. ghettos. Mildred writes a stirring letter to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, who refers her to the American Civil Liberties Union. Once the ACLU puts Cohen and Hirschkop on the case, the suspense kicks in. And the nation does get a glimpse of the drama, as evidenced by a CBS News segment that summarizes the events. As with the talking heads, Buirski uses this footage to keep us oriented in the story, without narration.

Footage of Virginia Klansmen, officials and citizens making ugly, silly, racist statements provides contrast to the Lovings’ quiet dignity. Caroline County Circuit Court Judge Leon Bazile makes a spectacular villain. His ideas on the origin and purpose of the races must be heard to be disbelieved.

True to form, the Lovings decline the invitation to their own Supreme Court hearing in 1967. They are content to wait for the results at home. Mildred says later that she wasn’t in touch with the civil rights movement. “All I knew was what everybody else saw on the news.” Her defiance of Virginia law was a simple, personal matter: “It’s just not right.” Fearing the weight and scrutiny of a Supreme Court decision (Loving v. Virginia, Richard pleaded with the attorneys to just keep the case local, to try to appeal to county judge Bazile’s conscience. When Cohen tells him gambling on a racist’s change of heart just won’t cut it, Richard goes along with the plan. Not a man of words, he sends along a message to the highest court in the land anyway: “Mr. Cohen, tell the court that I love my wife, and it’s just unfair that I can’t live with her in Virginia.”

Black-and-white photos by Grey Villet.

Steven Boone is a writer-at-large at Capital New York, contributor to Fandor’s Keyframe blog and Indiewire’s Press Play blog. He experiments with images and video at Hentai Lab.